The only thing worse than overused machinery is underused machinery, and a sailing vessel’s auxiliary engine is likely, perhaps hopefully, already underused under normal circumstances. One of the most familiar refrains I hear from boat owners, after a failure is, “It was working fine.” Indeed, most equipment won’t telegraph a warning in advance of its failure.

It’s not uncommon for engines to develop issues after the offseason layup, shortly after being placed back in service. Fortunately, many of these can be avoided with regular inspections and preventive maintenance.

Raw-water pump impellers are among the most common post-layup failure items, and this is very easily prevented by religious annual replacement at spring commissioning. Impellers are relatively inexpensive, the peace of mind afforded by their annual replacement, regardless of hours accumulated, is well worth the price. When replacing your impeller, be sure to closely inspect the cover plate for signs of wear. Visible discoloration usually isn’t an issue, however, any surface defects that can be felt mean the plate needs to be replaced (or turned over provided no embossed or debossed writing is present). Also, inspect the cam; if it is worn, then the pump capacity will be reduced. Some are replaceable, others aren’t. If the latter, the pump would need to be replaced.

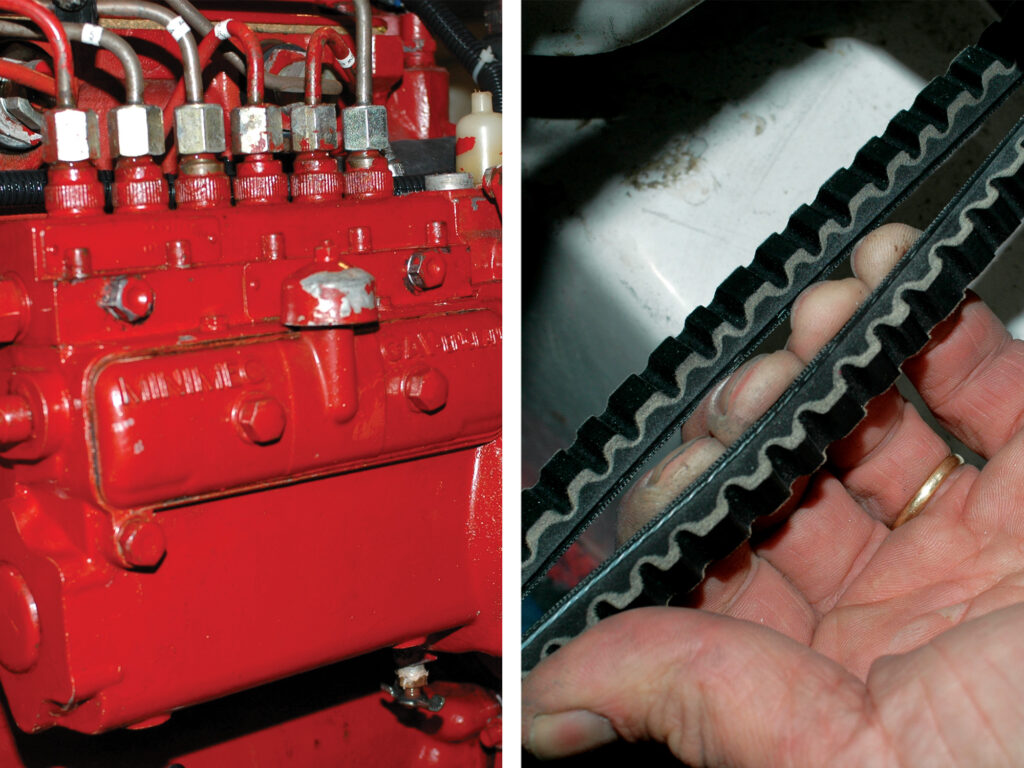

Belts are the next most common post-commissioning failure, and they too are relatively inexpensive. If your goal is maximum reliability, go ahead and replace them every two to three years—again, regardless of use. They do age and deteriorate even while sitting idle. When carrying out the replacement, look for signs of uneven wear, which is indicative of misalignment. Many V belts I encounter are overtensioned, which leads to premature circulator-pump and alternator-bearing failures. Even many professionals don’t get this right. If you are in doubt, use a Gates Krikit belt-tension tool.

Next, look closely at the entire exhaust system. This includes the gasket under the mixing elbow, the mixing elbow itself (corrosion is its nemesis, even if it’s stainless steel), hoses (any cracking is too much), the muffler (the drain screw often corrodes), hangers or supports, and the transom outlet. Be certain to look carefully at the latter, with a flashlight, if necessary, both inside and outside, because these can corrode and perforate or crack. If it’s stainless steel and you see any brown “tea” staining, it’s a clear indication the alloy has gone from passive to active; i.e., it’s corroding.

One of the most familiar refrains I hear from boat owners is, “It was working fine.” Indeed, most equipment won’t telegraph a warning.

Carefully review your engine’s electrical system. Look for loose or unsupported wires. Small auxiliary engines are prone to vibration, and any wires (or hoses, for that matter) that are not well-secured will chafe. This, in turn, can lead to a short circuit. In the best-case scenario, a fuse will blow and something, including the engine itself, will stop working. In a worst-case scenario, no fuse is present, and the short will lead to an overheated wire and potentially a fire.

Of all the positive DC wires aboard your vessel, only one is not required to have overcurrent protection (it is not prohibited from being protected; it’s simply not required for ABYC compliance), a fuse or a circuit breaker: the DC wire that supplies current to the starter. Therefore, the integrity of this wire is more critical than any other aboard. It must not make contact with any part of the engine. It should leave the starter—the post should be booted for insulation against short circuits—and the next securing point should be the vessel itself, typically a stringer.

For maximum reliability, replace your belts every two to three years, regardless of use. They do age and deteriorate even while sitting idle.

Finally, look closely over the fuel system for deterioration or damage, particularly any hose that enters the primary filter from the tank or manifold, and those that leave the filter and travel to the engine (once again, chafe is the key culprit). Then, pay attention to metal pipes that carry fuel from the lift pump to the injection pump, and from the injection pump to the injectors. Finally, inspect the return lines.

Metal pipes can rust. If they are missing their keepers, they can chafe against each other. This can be especially dangerous on a high-pressure line because a leak will spray high-pressure atomized diesel into the engine space.

You simply can’t spend too much time looking over these critical systems before leaving the dock or mooring for the first time.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.