How do you plan for a sailing voyage that promises extended time at sea? Aboard our Stevens 47, Totem, our family’s circumnavigation has included a number of memorable passages, enough to appreciate that each one requires careful research and preparation. And so, after a prolonged pause from voyaging brought on by an extensive refit of Totem, and the pandemic, we’re making our plans for sailing into the Pacific with extra care.

Careful planning isn’t called for just because we’re rusty, although what should have been a year or two in coastal Mexico will stretch to nearly four by the time we cast off for the South Pacific. What we’ve learned from past voyages is that it’s always appropriate to plan carefully, and even more so here because of the series of passages between relatively remote islands that our first crossing will set up. Here’s how we kick off that planning: with a zoomed out, big-picture view of the seasons.

Big-Picture Planning

A comfortable crew is a happy crew, so choosing good conditions sets up an easier and safer passage. But gazing at the trees on a hike tells you nothing of the forest and hazards that could be waiting weeks or months ahead. For sailors, focusing on the next passage creates a blind spot for seasonal hazards. Hurricanes, severe lightning, frequent gales, and monsoon winds from the wrong direction are a few ways discomfort and unsafe conditions force a stressful reality.

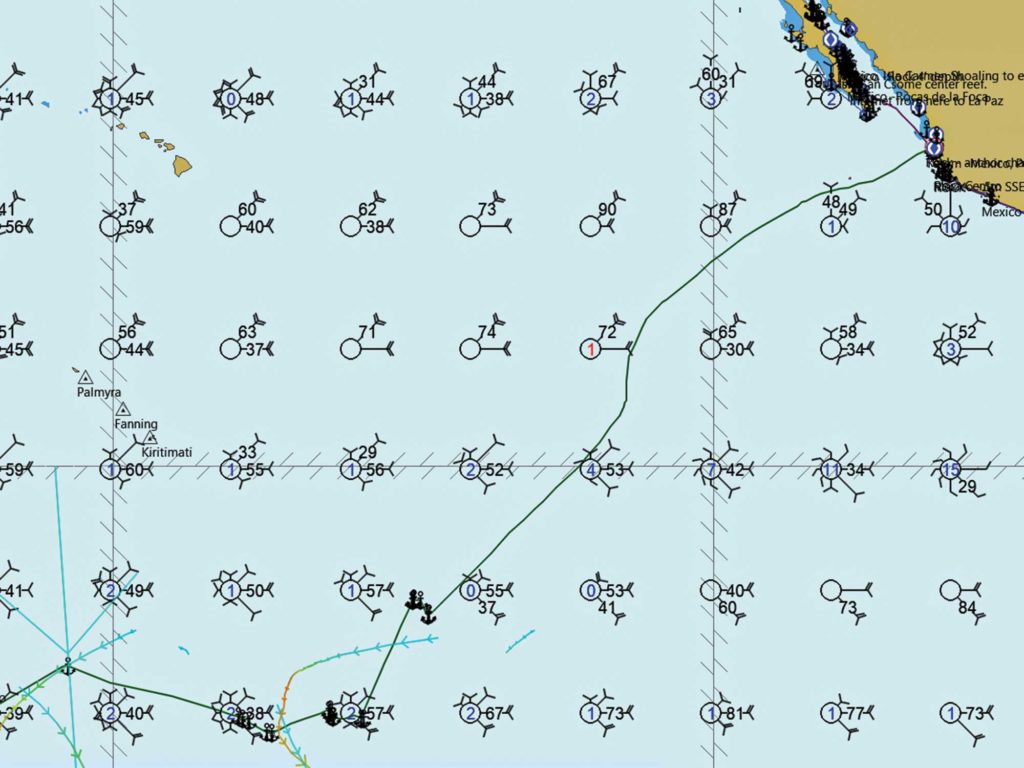

How do you work out that overarching plan? A fundamental task is to review pilot charts for a particular region to consider timing. These charts show monthly averages in wind directions and strength, ocean currents, storm tracks, average number of gales per month, and other weather data.

Jimmy Cornell’s World Cruising Routes is another way to make big-picture plans. This tome distills the information encompassed by pilot charts into passage-by-passage recommendations, with notes on the best and worst time of year for each. These recommendations are a great shortcut to see when it’s good to sail from, say, Mexico to the Marquesas, but won’t provide the bigger view a regional pilot chart offers.

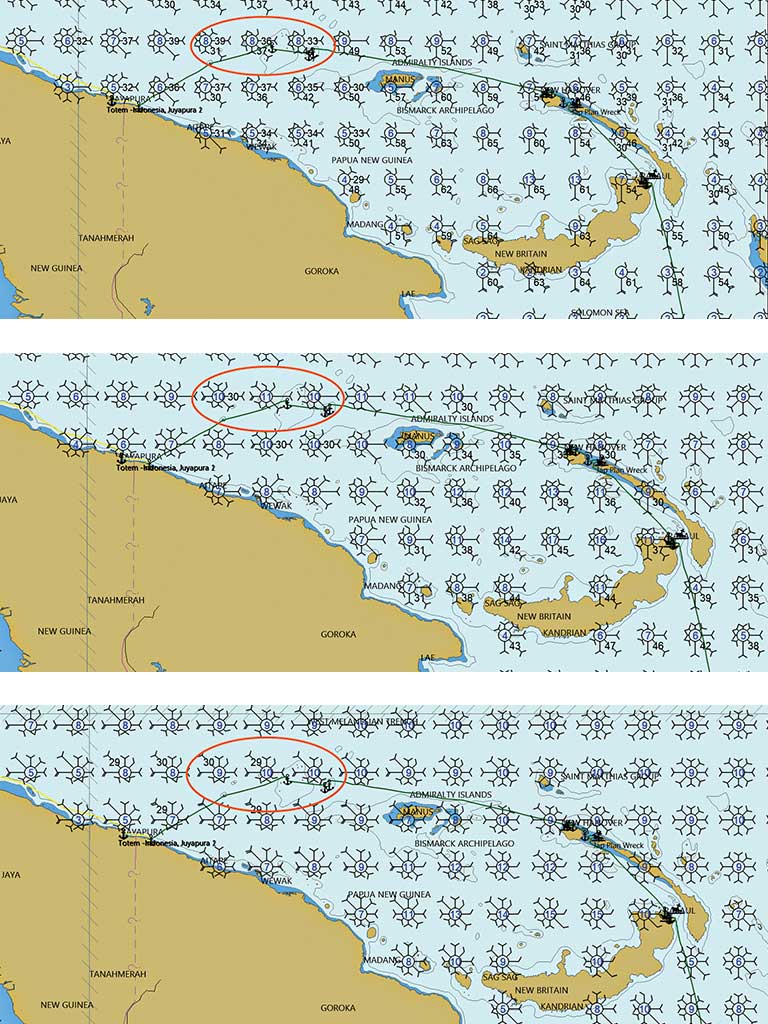

What weather features bookend the cruising season in the region you will cruise? Does the season end with a hard stop, such as reversed wind direction in monsoon regions? We were lucky when we were sailing Totem over the top of New Guinea because of a later-than-expected arrival of a monsoon change. When it arrived, it would bring headwinds, and we were grateful to have extended calms to get west while they loitered from the forecast.

Or will the seasonal transition be more like cruising in New England, where mild summer conditions give way to cold temperatures and frequent gales? The stress from running late in a seasonal change might feel 1,000 nautical miles away from an idyllic anchorage in the good season, but the good feeling is gone when weather windows for an intended passage stop opening.

For boats headed along the storied coconut-milk run of the South Pacific, planning means debunking a popular cry claimed upon arrival in French Polynesia from the Americas: “We’ve crossed the Pacific!” Declaring “mission accomplished” promulgates the perception that once you arrive, the hard part is over. While it might be the longest passage in a westabout circumnavigation, French Polynesia is only about one-third the distance across the Pacific. There’s no easy way to reverse those miles, so another part of big-picture planning is the exit strategy.

Plans and exit strategies are further complicated by the pandemic. In the past, gaining entry to nations in Oceania was mainly a matter of having current paperwork and providing advance notification for some countries. Our prior Pacific crossing aboard Totem was marked by a series of three- to five-day passages after our 19 days of sailing to the Marquesas. Planning for the upcoming Pacific sailing, we anticipate fewer short hops and several longer passages with at least three in the 2,000- to 3,000-nautical-mile range.

Departure from Mexico is best made after the North Pacific high sets up west of Baja and Southern California, bringing better wind to an otherwise fickle wind region. This could be in March, but in reality, finishing Totem’s 40-year refit in preparation for future voyages might push our departure closer to the transition to hurricane season. This is a bookend we take very seriously.

Our exit strategy after a season in the South Pacific is based upon countries we know we can access. It’s a moving target due to the pandemic, but our endgame will be one that won’t look to the conventional destinations of New Zealand or Australia. Instead, our gaze is turned northward with the hope that one or more of the islands between Fiji and Guam will provide the opportunity to continue a westward migration while flipping hemispheres to remain outside a zone of active hurricane risk.

Set the Route

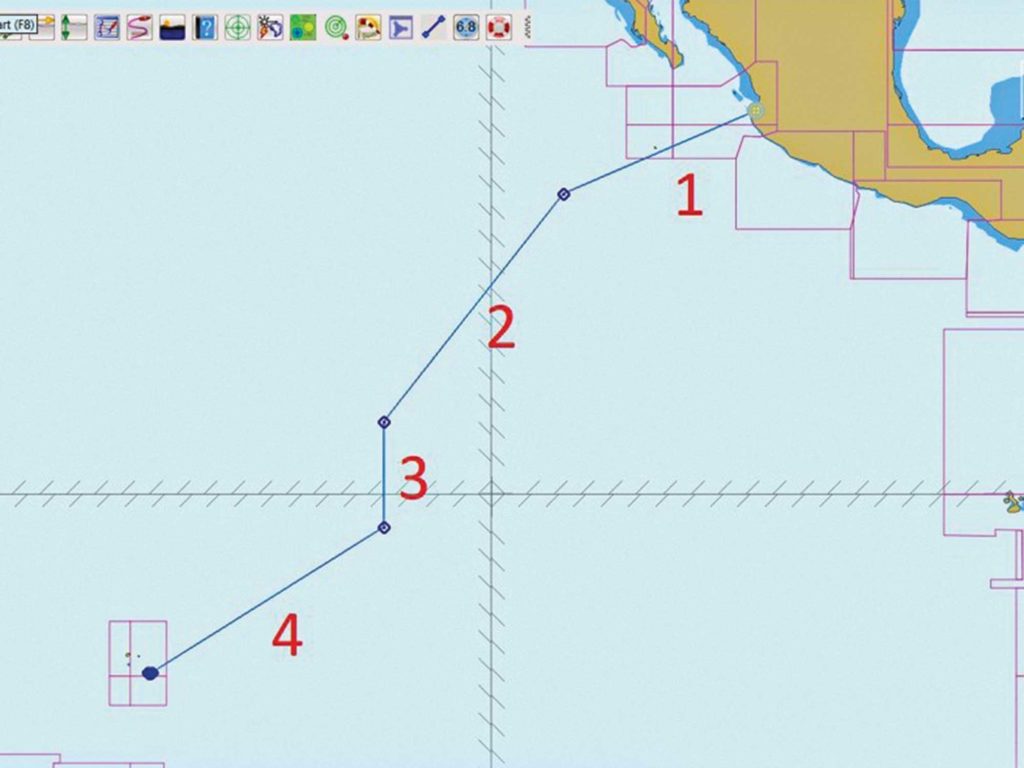

When creating a route for a passage, we begin with the start and end waypoints. The resulting track might be enough for a simple rhumb-line course, but usually there are hazards in the path. Additional waypoints added between the original two establish a route around fixed hazards. The goal is to create a route that is unquestionably safe.

Once we’ve added waypoints around all hazards and tweaked them for efficiency, we zoom in to ensure that every mile of our passage is hazard-free. Remember, electronic charts might not show small hazards when zoomed out. The consequences of not spotting them span from unfortunate to tragic loss of life. The most fundamental goal of creating a route is that it is free of fixed, known hazards.

From this safe path, we can modify the route to incorporate sailing strategy. This can be to avoid a foul current, get to better wind sooner, dodge degrading weather, and many other reasons. In practical terms, this means that our passage from Mexico to the Marquesas has four distinct legs.

First: getting away from the coast. The region from which we’ll depart has variable winds that can make for a slow start to a very long passage if not accounted for.

Next come the northeast trades. They make for good and easy sailing but come with a tricky finish in staging for the best place to cross the ITCZ.

Then it’s time to cross the ITCZ’s doldrums. This area of little wind and many squalls is dynamic, shifting north to south and getting wider and narrower. The least amount time spent there, the better.

Finally, we’ll encounter the southeast trades. Within a few degrees south of the equator, these winds kick in for a fast home stretch to the Marquesas.

Each stage has a common set of conditions and tactics. We’ve also found that it helps shorten a longer passage by setting milestone (well, waypoint) goals along the way. At each, adjustments can be considered to account for weather or notice to mariners of possible developing hazards. Going north from Grenada in the Caribbean, for instance, there is one such notice to avoid the area known as Kick ’em Jenny, which is an underwater volcano that, when active, is best sailed around. Again, if you change course for a safer and more efficient route, zoom in, from start to finish, to ensure that no fixed hazards will be met.

Pick a Weather Window

The weather in which you depart to sail across a bay or ocean is a choice. Interpreting weather tools successfully takes practice. Hiring a weather router can be a terrific way to ensure better passage weather while improving your own weather game.

But whether you plan to forecast on your own or rely on a router, start with a “we’re ready to depart on” date, rather than fixed departure date. It lowers a crew’s disappointment should the weather not be right to set out in. Look at weather patterns well in advance of the ready-to-go date. This can reveal trends helpful to routing strategy, the likelihood of getting underway when you hope to, and what the weather might be like. And look at the broader picture. Big weather far away might not have a direct influence, but it can deliver a complicating sea state.

Some passages will promise to be a joy, with terrific sailing, or tough-but-manageable conditions but with no hard stop at departure time because of the approach of bad conditions. When the forecast shows that the weather window will shut hard at some point during the crossing, then consider treating the passage more like a delivery. Set and stick to a minimum and realistic speed to arrive in advance of bad weather. If this includes the notion of racing to stay ahead of the bad weather, then there probably isn’t adequate buffer unless you are truly prepared for and capable of the consequences of running late.

Since forecast accuracy decreases after three days, longer passages require more of the crew. On Totem’s 1,000-mile voyage to South Africa from Madagascar, a major gale showed up on the forecast about halfway through the passage. There was no bailout option. Forecast timing had us arriving in Richard’s Bay six to nine hours ahead of when gale-force southerly winds would smash into the strong, south-flowing Agulhas current. This recipe for disaster kept us pressing hard to maintain a buffer. Still, the gale arrived a little early, and we bashed our way through brutal conditions—but only for the last 5 miles.

Know Destination Details

When sketching out the passage plan, learn about the arrival formalities at your destination. It might be as simple as an automatic visa, using current vessel documentation and valid crew passports. Or it can be complicated, and our Pacific plans play out that version. Here are the questions that we’re asking:

- Are visas granted on arrival? Will they last long enough for what we are planning?

- Is a cruising permit required?

- Does the country require advance permission or notification for arrival?

- What is the arrival procedure and documentation required?

- Is an agent helpful (or necessary)?

Our plans to take Totem to French Polynesia tick many of these boxes, starting with visas. Like many other nationals, US citizens are granted a 90-day visa on arrival. For those who want more time to explore the archipelagoes and islands, the process to apply for a longer visa begins at a consulate months before actual arrival.

Permission to arrive isn’t a given. Arriving in certain Pacific nations without permission, when a permit or visa is required, has resulted in boats turned away, or worse. A German crew arriving in New Zealand were fined, had their boat confiscated, and were deported—with a police escort.

When approaching the Polynesian islands, additional advance notice is required to alert officials of a boat’s pending arrival. Once ashore for formalities, a bond must be posted to secure the cost of repatriation should you be required to depart the country by air. The layers of this can mean it’s easier to secure an agent to facilitate the process—a step Totem’s crew is taking. Arriving without knowing the requirements and having the proper documents can mean being turned away or fined, or both.

In addition to the legal requirements of a new destination are the practical ones. What charts are most accurate for the area, if any? We usually have at least two chart sources for any region. Often enough there are discrepancies between them, a reminder that the burden lies ultimately on piloting skills. When we were in Madagascar, a cruiser lost his boat on a charted reef. One chart showed a submerged reef, while the other showed a visible reef. He didn’t see the reef and assumed that the second chart, the one he was using, was wrong.

When a country doesn’t have resources to update charts or aids to navigation (something to which research should alert you), proceeding with exceptional caution and conservative choices is good seamanship.

The passage to the Marquesas and beyond excites us so much, in part, because it’s not just one extended passage, but the promise of several extended voyages as well. And shaking out the cobwebs during the planning process reminds us of a core characteristic of cruising that’s one of the reasons we love it so much: The opportunities to continue learning, and to improve our basis for understanding the dynamics of the world around us, are ever greater and more rewarding.

Behan Gifford and her husband, Jamie, are frequent CW contributors. They and their family are currently in Puerto Peñasco, Mexico, having recently completed a 40-year refit of their Stevens 47, Totem.

Plot a Voyage

Friends don’t let friends set autorouting and go! It might be fine for a snapshot, but no program anticipates the true complexity of a route.

- Begin by plotting in your starting point and destination.

- Zoom in to adjust departure and arrival points.

- Add waypoints to route you safely away from your departure point, and into your destination harbor.

- Add waypoints that shape the stages of your passage.

- Mark hazards (weather buoys) or possible hazards (debris areas) from research.

- Trace a zoomed-in view of the route for any charted hazards.

- Research and add bailout options and new routes in the event of changing circumstances that require rerouting underway, gear breakdowns, or unexpected weather or sea conditions.

Pilot Charts, Four Ways

Paper Pilot Charts:

Classic volumes are sold as a bound atlas, and are based on data going back to British Admiralty days, with one page for each month of the year; each book covers a major ocean region.

Cornell’s Ocean Atlas:

This spiral-bound book organizes monthly pilot charts for portions of the world in which cruisers are likely to be interested: a succinct format that allows breadth of coverage, and data is based on more-recent trends. These were developed by Jimmy and Ivan Cornell.

OpenCPN’s Climatology Plugin:

This free overlay to the open-source charting software allows users to scroll through historical weather data. It can be found online at opencpn.org/OpenCPN/plugins/climatology.html.

PDFs from the US Navy:

These are downloadable charts in PDF format, and are free from the US military, and are a no-cost option to get the information you want. Begin your search at www.usno.navy.mil/FNMOC.