It was an uncharacteristically hot June day for the Pacific Northwest when Duracell was lifted from the yard outside Seattle. It had been sitting there for the previous 25 years, and it was time for the boat to move to our yard on the Olympic Peninsula. Even at 6 a.m., a small crew of family and friends gathered to watch Duracell get lifted off its mossy stands. Among them was the man who had given us the boat two years after my husband, Matt Steverson, stumbled upon his sailing-forum post: “Mike Plant’s Open 60 Duracell—What Next?”

The three guys who moved Duracell seemed unfazed about transporting a 15,000-pound vessel (no mast, thankfully) some 100 miles. Associated Boat Transport moves about 600 boats a year in the Pacific Northwest. After the truck and trailer shimmied into the cul de sac, they carefully, inch by inch, slid Duracell onto a tuning-fork-shaped trailer. Big hydraulic hands lifted the boat a few inches off its stands. Then the movers adjusted the jack stands, the boat slid in a little farther onto the trailer, the stands were adjusted some more, and so on for about two hours, until the trailer was all the way under the boat.

It was an incredible sight, watching this boat float through a neighborhood and up the highway’s on ramp. Driving over the Tacoma Narrows Bridge above Puget Sound, Duracell had the shimmering ocean under its hull for the first time in a quarter century. After some impressive backing up into our driveway, the movers lowered the boat onto a clean blue tarp, wiped the sweat off their brows, downed some ice water, and left us with the boat project of our lifetimes.

The first few weeks with Duracell in our backyard felt a bit like Christmas morning. It gave us butterflies to raise the blinds and see Duracell only feet from our bedroom window. Matt had known for some time that he wanted to build or refit a boat, but he never dreamed he would get this boat.

To understand why this is the only boat for us, you first have to understand our vision. We see Duracell becoming an extraordinarily fast, safe and comfortable cruising boat.

In its current condition, Duracell is not fast, safe, comfortable or even seaworthy.

But it will become all of that.

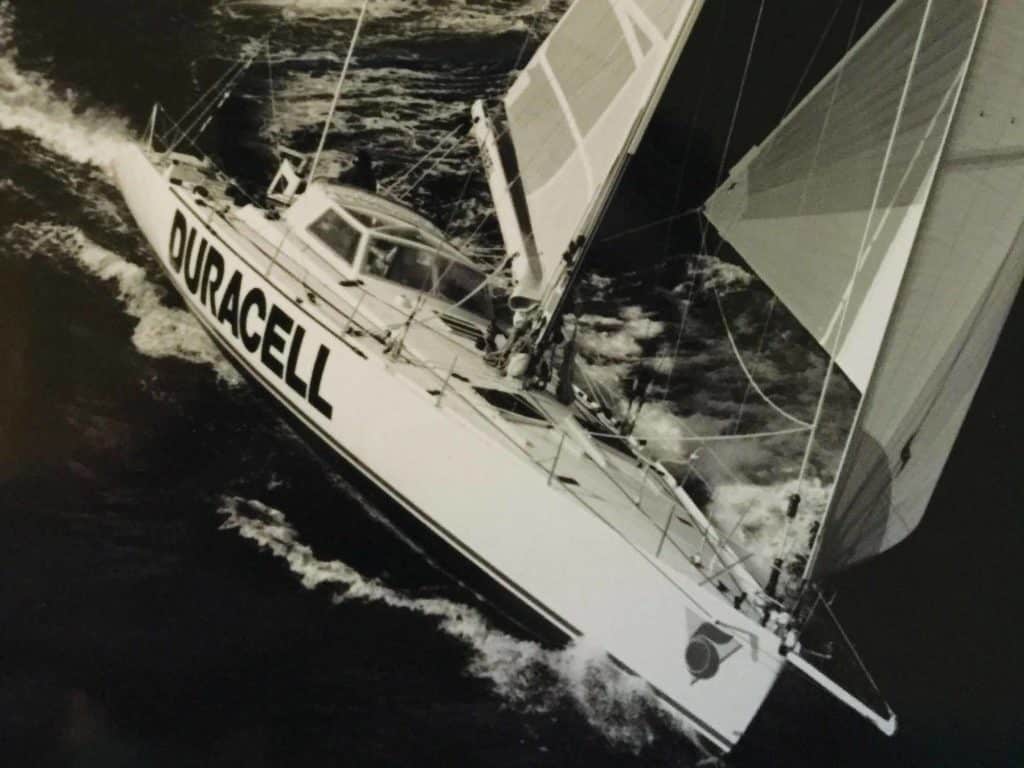

Duracell is an ocean-racing sailboat designed by Rodger Martin and built by Plant to race in the first Vendée Globe in 1989. During the singlehanded nonstop race, a small part on Duracell’s rigging was damaged, forcing Plant to seek refuge in a harbor on Campbell Island in New Zealand. There, a storm caused his anchor to drag toward the rocky shore. Locals motored out from shore to rescue Duracell. Receiving outside assistance disqualified Plant from the race, but he finished anyway, in seventh place, beating the American record for solo nonstop circumnavigation with a time of 135 days. Right after the Vendée Globe, Plant circumnavigated the planet on Duracell again in the BOC Challenge, coming in fourth place.

John Oman bought Duracell in 1991 and won the Pan-Pacific. Reports at the time say that the boat sailed the fastest course of any yacht in the race, reaching Osaka, Japan, in 32 days, 16 hours. The boat averaged 8 knots for the 6,200-mile marathon.

Oman then began a solo nonstop circumnavigation. It was during this voyage that Duracell collided with a cargo ship near the equator, dismasting when something on the rigging caught something on the cargo ship’s side. Oman motored aboard Duracell back to Turtle Bay in Baja California, Mexico, where he refueled, motored on to San Diego, and then trucked Duracell to his home outside Seattle.

So, yes, this is a fast boat.

Now, let’s talk about the boat being safe. The first 12 feet of the bow has an anchor locker and a wet stowage locker, bookended by bulkheads. The first bulkhead, 6 feet abaft the bow, sections off the anchor locker. The second bulkhead, 12 feet abaft the bow, sections off the wet storage locker. If the boat were to have a head-on collision, these watertight spaces serve as sacrificial limbs. They can be punctured, damaged, even torn off, and leave the rest of the boat afloat. There is also a 12-foot, watertight stowage locker in the stern. If a rudder rips off, the space can fill with water, and the boat will stay afloat.

So, although the boat is 60 feet long, there is really only 35 feet of living space. But with a width of 15 feet, that’s plenty of room to live in. We’ll get to what that means for “comfort” in a minute.

The boat was constructed to sail around the world, and certain features reflect this. For example, it has beefy ring frames, and the fiberglass is laid up with vinylester resin, making it stiff and strong. It has a thick foam core. It was built to be strong but also light.

Of course, there’s a lot to do before the boat will become truly safe. Currently, it can’t float, let alone sail. First of all, the keel is not attached. Oman removed the 10,000-pound, mostly lead fin keel when he transported it from San Diego. That keel is now lying on its side in our yard, looking like a giant boot. The boat also has no mast, though it came with sails that we hope to use. Because of their size and number, just unfolding them is a full day’s job.

Finally, we get to “comfortable.” Two major components make a cruising vessel comfortable: a welcoming, livable interior and seakindliness. Duracell is long, narrow, fast and stiff, with a plumb bow—all things that make it cut through water like a knife. Currently, the interior is anything but comfortable. It was designed to race, with no galley, settees, V-berth, head or any other creature comforts. The boat did come with what looks like a Porsche race car chair in the pilothouse; apparently, Plant allowed himself that comfort, along with a toilet tucked in a corner. The fact that the interior was left unfinished to keep it light makes it a blank slate, which is exactly what we want.

And what was inside Duracell, we have now removed. In fact, the first two months of the refit have mostly been removing stuff from the inside: all the original wiring, electronics, plumbing, batteries, tanks, DC distribution panel, sails and two engines. We’ve hauled several truckloads to the dump, and a small mountain of salvageable things is in our carport. Of all the things that came off or out of the boat, a few notables are four petrified rats, lots of 1990s electronics, 25-year-old seawater in the ballast tanks, a Yanmar engine and a Balmar generator.

What’s left is a fast, safe shell that we can make into a comfortable cruiser. Matt often squeezes his hands under his chin with an exuberant smile and exclaims, “Baby, it’s going to be the coziest, fastest cruiser in the world!”

As our friend Graeme Esarey said after refitting Dogbark, also an Open 60 (that raced against Duracell in 1990): “Different boats for different folks, but I know of no better cruising platform for us. This era of Open 60 is a go-anywhere-safely-and-comfortably boat that could be used for expeditions, sail training, or just a go-fast-and-see-the-world platform.”

We plan to do all those things—and more.

And we know that Duracell will be able to handle our plans. Our pre-purchase survey revealed eight spots of moisture in the hull but no signs of delamination. Matt took core samples of three of the eight spots, and all were bone-dry. I waited until he was out of earshot to ask one of the surveyors “So, what do you think? Is this a worthy project?” His response was quick: “Oh, this is definitely a worthy project.” Then he added, glancing over at our beater of a car, “Especially if you have some money.”

Refitting Duracell will not be cheap, even though we will do all the work ourselves. We don’t exactly have lots of dollars to spare on boat parts, and days spent on Duracell don’t pay. Matt works as a shipwright, and I work for a nonprofit, which is rewarding but not high-paying.

As of now, Matt works on Duracell evenings and weekends, after working on other people’s boats all day. He would love to work on Duracell full time. Our hope is that by producing weekly videos on our YouTube channel, the Duracell Project, we might slowly be able to afford to work on it more and more. If the YouTube route doesn’t pan out, that’s OK; the project will just take longer, happening on evenings and weekends, and we will purchase things as we are able.

The goal is to have Duracell in the water by the time Matt turns 40. He’s turning 37 soon.

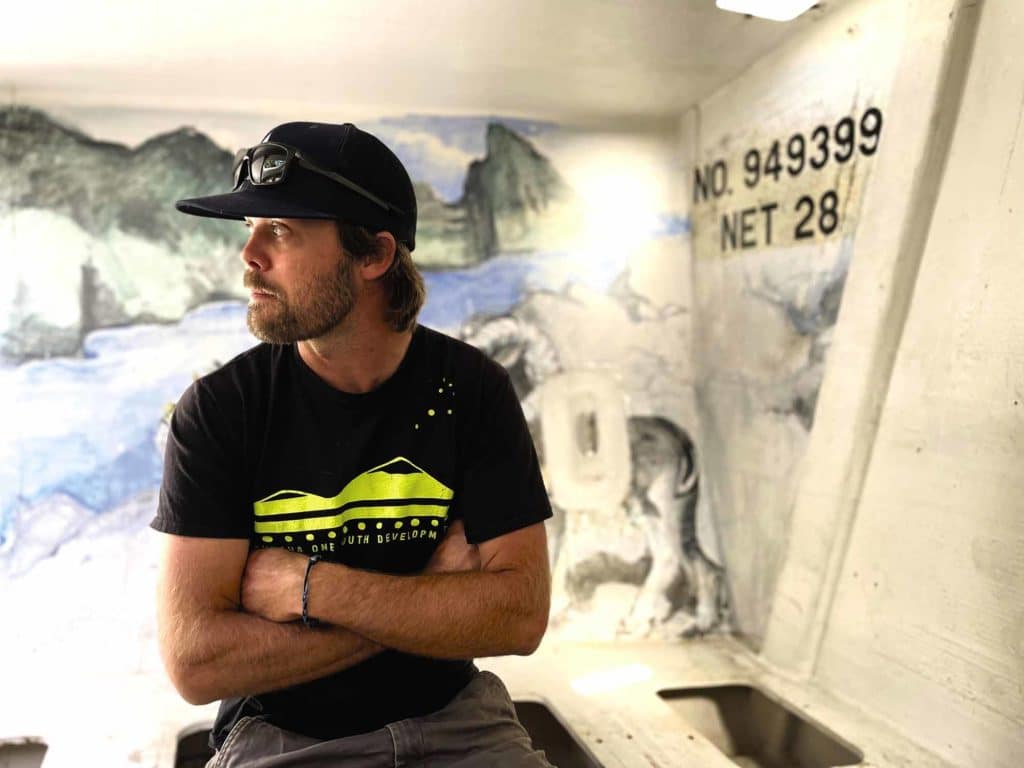

Former science teacher Janneke Petersen and her husband, Matt Steverson—a seasoned sailor who was part of the winning crew in the inaugural Race to Alaska in 2017—are well into their ambitious refit, which they’re chronicling on their YouTube channel, the Duracell Project. Look for updates on their project in future issues of CW.

Removing the Engine

How do you remove two heavy, old engines from beneath the cockpit without spending a ton of money renting a crane?

First, you cut out the cockpit sole. Then, you build a series of gantries. Then, you move each hulk of machinery out of the engine room, into the cockpit and aft to the stern, where you use the biggest gantry to get it off the boat. And you drop an engine only once (see episode 4 of the Duracell Project on YouTube) without damaging the engine or the boat—which says a lot about the boat.

We hope to sell the old Balmar. There are two possibilities for the Yanmar: Sell it to add a few dollars to the Duracell kitty, after we replace the wires and hoses that were chewed through by rats; or convert it into a generator for a serial hybrid-propulsion system. We’ll see.

Removing the Cockpit

After a few weeks of removing all electrical-, mechanical- and plumbing-related stuff from the interior, it was time to start cutting up the boat. This was an exciting moment: the first modification toward reshaping Duracell into our dream cruiser.

The aft ballast tanks came out through the space where the cockpit sole used to be. For us, one important attribute of a dream cruiser is a large, raised pilothouse. We know that from our first boat, the 39-foot home-built sloop Louise, where we spent countless hours as liveaboards in our pilothouse sipping morning coffee, chatting and gazing out at the watery world.

Duracell has a tiny pilothouse with faded plastic windows. It will be replaced with a pilothouse modeled off Louise’s but bigger. We envision stepping into Duracell from the outside through a small door that requires a slight stoop, leading into a salon that is level with the cockpit and above the water. The salon area has two 6½-foot benches on either side, and a table that can easily pop up and tuck away for passages. Windows are on all sides. Going forward, we walk down three steps to the main deck where the galley is, to starboard. The pilothouse stretches forward, encompassing the galley and allowing light to pour in.

Having a pilothouse is also ideal for passages. Because there will be windows on all sides, the person on watch can be inside and still keep a close eye on things. Under the pilothouse sole will be the engine room, and under the benches will be the quarter berths; in other words, the engine room will be sandwiched by two quarter berths.

With the cockpit gutted, we can really start to envision this new layout.

Building the Shed

Winter was coming and we needed a boat shed, especially with a gaping hole in Duracell where the cockpit used to be. We decided to build a bow shed using free designs (for a greenhouse, actually) that we found online from the Louisiana State University College of Agriculture.

We chose a bow shed because it’s relatively cheap, it can be built relatively quickly, and we might be able to reuse it for future boat projects or even repurpose it as a tiny house. Over the course of one long week, we completed this necessary project, with the help of Petersen’s uncle.

First, we laid out around the boat where the holes were going to go, and rented a post-hole digger to dig six holes on either side. We poured the pilings and set 4-by-4 mounts in the pilings. Each frame consists of an 8-foot-long 4-by-4 attached at the footing, standing up attached to a molded-wood I-beam built out of 20-foot-long 1-by-4s on either side of 2-by-4 shear web, built on a jig for consistency. To make the jig, we drew out the shape of the frame onto a plywood platform, and then spaced out blocks into the shape of a frame. To make a frame, we set the spacer (shear web) blocks on top of the jig blocks, and placed the 8-foot-long 4-by-4 at the bottom. We then bent the 20-foot-long 1-by-4s around the jig on both sides, and screwed and glued them to the spacer blocks. Then we pulled the frame off the jig.

We built 12 frames (two per rib, if you will) off the jig. Each frame is mated with a footing at the ground and attached to a 2-by-6 center beam at the top that runs the length. Once they were all attached, we reinforced it with four 2-by-4s that run the length, and two 1-by-4s that are diagonal.

We sheathed it with oriented strand board toward the bottom for strength, and attached eight 2-by-4s from the boat stanchions to the shed, giving it lateral stiffness. Then we covered it with white shrink wrap.

Voilà! Dry and cozy for working during the dark winter evenings. Also known as a gothic arch, it also looks quite elegant.