Panchita was a callejera, a street cat who adopted us. She was one of thirtysomething animals we fostered while in Puerto Peñasco, Mexico, during the extended refit of Totem, our Stevens 47. The rescue agency where our daughter Siobhan volunteered had offered to transport Panchita north of the border for adoption, but when the time came to let her go, we couldn’t do it. She was irrevocably one of us.

Now, we are learning what it means to go cruising with a pet. Here’s the best and the worst of what we’ve figured out so far.

Transitioning Aboard

To help Panchita transition from street life to boat life, we made nests for her around the boat that incorporated familiar smells and favorite things. There may have been a few extra treats doled out. We brought her favorite dried anchovies, familiar litter box, and a fleece throw dubbed “the magical blanket” because of the calming effect it has on her.

The first few days, she stayed mostly hidden, coming out to eat and use the litter box. Panchita gradually explored every corner of the boat in high-alert mode, tail down, creeping from cabin to cabin. During the next week, she gained confidence, and her tail returned to the happy-cat question mark position.

Getting Underway

We were advised in a Facebook group to harness-train her, so we could keep her secure as needed. There’s a mixed set of reviews about whether PFDs are effective for cats. Plan A was to keep her belowdecks, or in close reach in the cockpit, while underway.

Harness training is amusing at first: A cat buckled in for the first time may flop down and forget how to walk, or just look at you with a deeply offended expression. Panchita adjusted eventually. Dried anchovy bribes helped.

Eleven days after moving aboard, we set sail for a weeklong passage to Banderas Bay. She hated the engine, and she vanished into one of her growing list of hidey-holes when it was turned on. Under sail, she slowly became more comfortable moving around belowdecks and making occasional supervised visits to the cockpit.

Her favorite places were often near us, or in one of the nests we’d made for her. An unexpected, chosen refuge was the laundry hamper. Never, in nearly two years at our apartment, did she seek it out. At sea, it must have felt nice and secure, and it had the right smells.

The Poop

Who wants to deal with provisioning for kitty litter around the world? Not us. Some cruisers do, while others use beach sand (sounds like a great way to invite bugs on board). Still others work with what they find along the way. And then, there are cruisers who teach their cats to use the toilet.

On land, Panchita would cry to be let outside to do her business. She got used to litter, so we used that aboard too. We started toilet training with a kit that we found online after arriving in Banderas Bay, and it’s going pretty well so far.

Meanwhile, we also purchased Purina’s Breeze “litter system,” which a lot of cruisers like because you don’t need to stash as much litter. The pellets last longer, and it’s possible to wash and reuse them. They also won’t track sand into your bunk.

Keeping a Cat Safe at Sea

We did not install nets, but many cat owners do. Another calico, Poppet, is circumnavigating on the Valiant 40 Sonrisa with her humans. Here, she demonstrates the attitude of many cats regarding lifeline netting.

Will we install nets? I think we’ll wait and see how curious our ship’s cat is. For now, we feel comfortable with the combination of her general caution and disinterest in being on deck underway, using a harness to secure her if needed, and remaining vigilant about her location when we are sailing.

Keeping a Cat Safe at the Dock or Anchor

Marinas aren’t a safe place for a curious cat. She might get into a place she can’t get out from, whether that’s trapped in the dock’s structure or inside an unfamiliar boat. Or, she might wander away and get lost. We’ve heard so many heartbreaking stories.

Aside from the danger to the cat, it’s a real no-no to get on another person’s boat (unless there’s explicit permission). The cat could do damage. Panchita has already found the nonskid on my standup paddleboard a nice place to scratch, and the nuisance damage from claws digging into, say, fake teak decking can get expensive to fix.

What if the cat lands in the water? It’s our biggest fear. Some liveaboards hang apparatus off the side of the boat while anchored or moored for the cat to self-rescue by climbing up. It could be a fishing net or a yoga mat, or any of a number of things.

In our first weeks with Panchita on board, that fear was realized. Late one night, she got out through a hatch we didn’t think was accessible to her. We only found out she’d gone wandering when she came into our cabin, soaked and meowing mad, around 3 o’clock one morning. Her bloodied claws suggest that she was lucky to get out of the water, probably by way of climbing barnacle-crusted pilings. High on our agenda is working out something to hang off the transom for her to climb, and to do some in-water training at anchor.

Previously, Panchita loved to be outside, and had free access to go in and out during the daytime at our apartment. Being mostly confined to a boat is a massive transition, but an essential one.

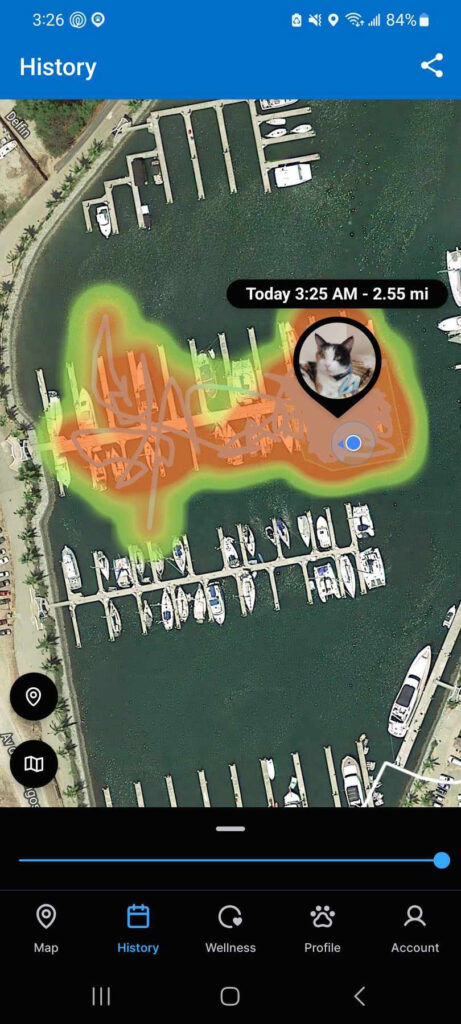

The Benefit of a Tracker

I can’t imagine not having a tracker. They come in two basic types (radio-frequency and cellphone based) with different advantages. We have both and will employ whichever is best suited to the current situation.

Tabcat was our first tracker. It uses radio frequencies. We decided this was a great fit with our intention to be in remote, disconnected islands. It’s a lightweight tag on Panchita’s collar that lets us home in on her location from 500 feet away. We can remotely prompt the tag to beep, and she has become conditioned (anchovies, again) to return to our apartment when it sounds. A Tabcat kit includes two tags, each with a battery life of up to one year.

After Panchita’s nighttime escape and unplanned swim, we also decided to try a GPS-type tracker. Tractive’s historical tracking feature was eye-opening: We could immediately see that she was getting off the boat when we didn’t realize it, and probably getting onto multiple other boats on the dock. We have since buttoned up her escape routes so we can sleep at night, and we set a perimeter alert so we are pinged if she goes beyond our safe, close range. It’s also comforting to know that if she does wander farther, the GPS/cellular network method will help us find her.

The tag is bigger than Tabcat’s, but our petite, 2-pound Panchita doesn’t seem to mind. The tag is also waterproof. It’s possible to remotely prompt it to make a sound or flash a light. It does need regular charging, about every other day, and for those hours it can’t be on. For that reason, some cruisers with Tractive tags purchase two.

This link Tractive gives you a 30 percent discount; the bigger cost will be the subscription, however.

Arriving in New Countries

It’s more complicated to arrive in a new country as a pet than to arrive as a human. Even if the pet won’t leave the boat (like the dwarf hamsters we carried to 28 countries), the pet should be declared, which usually means paperwork.

Pets should be microchipped and have current vaccinations. You may need a vet’s certificate of health from the country where you departed; you may be able to get one on arrival. Countries may require a titer test (proof of sufficient rabies antibodies) taken within the past few years. Others won’t allow your pet regardless of titer tests if they’ve been in countries with certain levels of rabies risk within a defined period of time. Every country’s pet-entry requirements are different and need researching.

Excellent veterinary care is available in Mexico, but we naturalized Panchita as a US kitty with a couple of road trips to a veterinarian in Tucson, Arizona. To avoid the 120-day quarantine that was formerly the norm, handwritten records in Spanish weren’t going to be enough. Plus, the titer test required spinning serum from a blood sample and then overnighting it to the University of Kansas (with results sent directly to Hawaii). Don’t tell my husband, Jamie, but those trips added up to around $1,000.

Health Needs

Cruisers invest a lot of preparation to care for the medical needs of the crew: giving CPR, and sourcing prescriptions or other medications that could be needed.

To do the proper sourcing for a pet, we attended a presentation by a cruising veterinarian, Dr. Sheddy, who addressed medicines to carry and how to handle wound care, near-drownings, poisoning and more. It was eye-opening. She’s seven years into her mission to provide free veterinary care to animals in need from aboard her sailboat, Chuffed. She shares practical, real-world advice for remote cruising with a pet on board, including medications for your pet’s first aid kit.

We’d Do It Again, But…

Most pets will increase complication, add costs, and affect the boat’s routing options. And, cruising might not be your pet’s idea of living their best life. You may already have a pet who is part of your family, and who will make the sacrifice willingly. But if you don’t have a pet yet, think hard before adding one if you plan to go cruising.For a more dog-centered point of view, see this recent article in Spinsheet magazine by our friend Cindy Wallach. She’s cruising the Caribbean with rescue pups Choo Choo and Pip, and has great insights.