Many boat owners are surprised to learn that shaft bearings, also called cutless bearings, are lubricated with nothing but seawater. Without its regular flow, the bearing and shaft can wear rapidly.

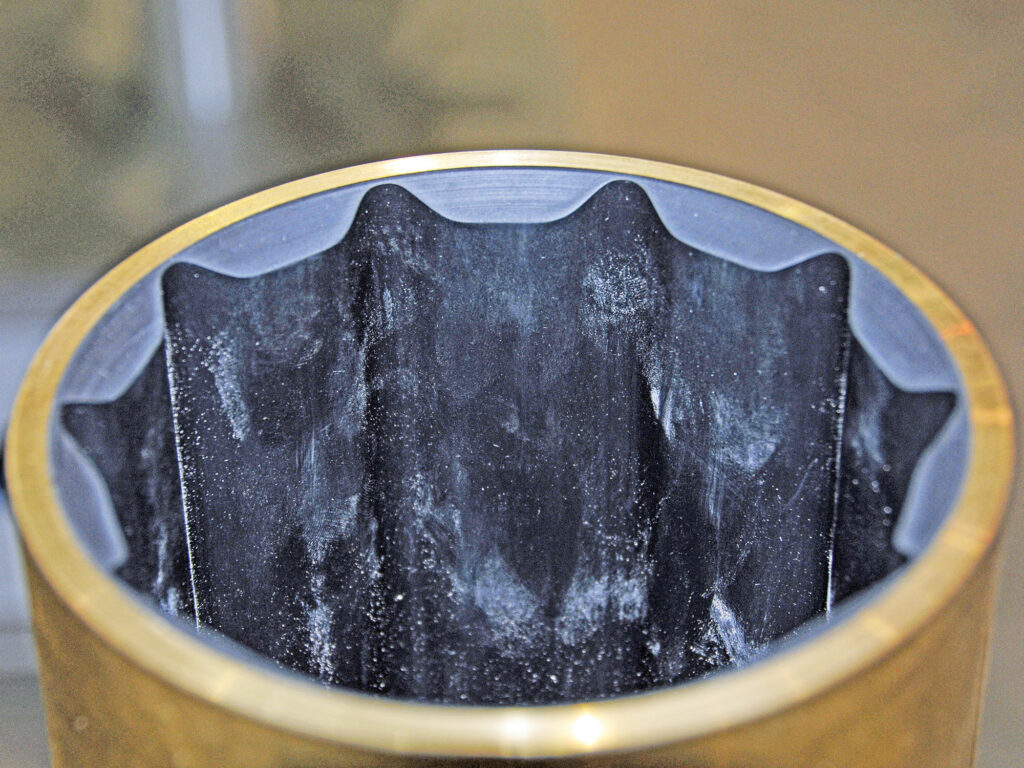

Most conventional bearings and bushings are made from relatively hard substances—some type of metal, from brass to steel—and are oil-lubricated. Shaft bearings, however, are almost exclusively made from rubber that is lubricated with seawater. The design, at least for DuraMax products, incorporates a few features that yield this surprising longevity.

The outer shell of the bearing is most often made from brass (not bronze), although bearings are available with a nonmetallic shell for use on aluminum and steel vessels.

The rubber, which is of the especially durable and oil-resistant nitrile variety, is flexible, so the bearing lands deform slightly when the shaft turns. This enables a water wedge to form between the bearing and the shaft, making for extremely low friction and wear.

Additionally, the soft surface is able to “absorb” grit and dirt until it can be flushed through the valleys between the lands.

Unlike hard bearings, rubber shaft bearings almost never fail catastrophically. Bearing life varies depending on several factors, but I’ve encountered bearings that were still within tolerances after 1,000 hours of use.

Even still, shaft bearings can fail prematurely if they are starved of their lubricating lifeblood: water. This can occur if a sacrificial anode is installed too close to the leading edge of a strut. For planing power vessels, the general rule is no less than a foot of clearance between anode and bearing. For sailing and displacement craft, 6 inches is plenty.

If the anode loosens and slides aft on the shaft, that can also block water flow. Barnacles and other marine growth, as well as carelessly applied antifouling paint forward of the bearing, can also impede water flow.

Shaft bearings should be installed with a light press fit. No more than moderate effort should be required to push or pull a bearing into its bore.

Sealant or epoxy should never be used to secure a bearing into place. If the gap between the bearing shell and the bore is too great, then a larger bearing shell can be turned down on a lathe to achieve the proper fit. Once the bearing is in place, it should be retained with set screws whose tips are pointed. These should “land” in dimples that have an angle that matches the screw tip, and that are drilled into, but not through, the bearing shell.

While engine-to-shaft alignment is a process that is fairly well-understood in the marine industry, shaft alignment with shaft bearings often represents a bit of a gray area for many boatyards. The prop shaft and transmission output couplings must be centered and parallel, and the shaft must also be parallel with, and be centered in, the shaft bearing.

Getting both of these right represents a delicate balancing act, one that often fails to achieve the goal on the bearing side. If the shaft passes through the shaft bearing in a manner that is not parallel, then “pinching” can occur. This is evident when viewing either end of the bearing. A gap might exist on one side, say at 3 o’clock, while the bearing’s rubber is compressed at 9 o’clock (the gap and compression location will be reversed at the other end of the bearing). Such a scenario leads to accelerated bearing and shaft wear because the shaft is unable to “float” on the water wedges, and because of vibration. Aligning a shaft with a bearing often requires adjustment of the strut or keel bearing carrier.

Finally, shaft bearings can occasionally suffer from swelling. This occurs when a hygroscopic (and thus incorrect) rubber bearing material is used. In extreme cases, it can cause the shaft to be seized by the bearing.

The proper clearance between shaft and bearings is detailed within the American Boat and Yacht Council’s Standard P-6, Propeller Shafting Systems, for shafts from ¾-inch to 4 inches.

It is highly advisable to fit new bearings to shafts, and to check the clearance before installing them, because oversize and undersize bearings are not uncommon.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.