A friend once said that the most reliable steering wheel is a tiller, but we live in an era when wheel steering prevails. Today, two rudders and two wheels have become de rigueur, with more linkage and points where corrosion and wear can become a problem.

Losing steering might not be as bad as losing the rudder itself. Both result in an immediate loss of control, but the steering is usually easier to remedy. Most designers and naval architects build in an ability to insert an emergency tiller and operate the rudder even if a cable has snapped, or if the linkage fails. (A broken rudder or rudder stock is another story for a future column.)

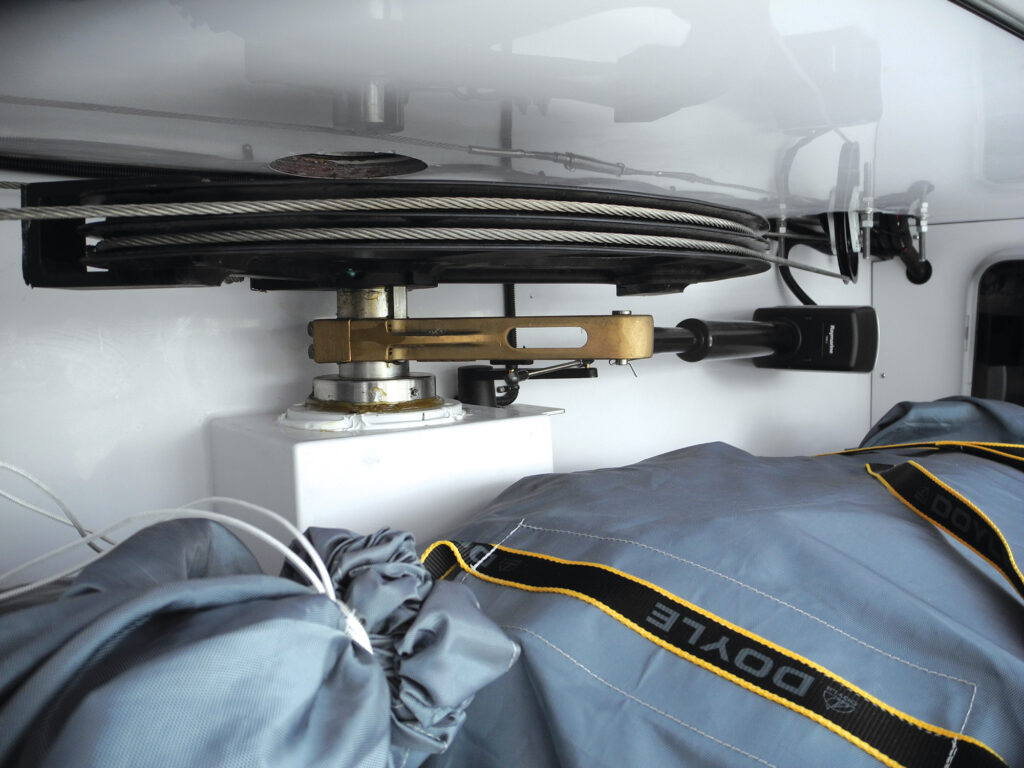

Chain-, wire-, pulley- and quadrant-type steering systems have proved reliable and relatively easy to service. They are referred to as a pull-pull design that converts rotary motion at the wheel into tension on one cable while the other is slackened. Components include securely fastened idlers and sheaves (pulleys) that route the wire or fiber cable from the helm to a quadrant that’s securely affixed to the rudder.

Another version of the cable system incorporates a dual-action single cable housed in a conduit. This system provides push and pull via a single cable. The push mode is less efficient, and the condition of the cable inside the conduit is hard to monitor. The system might be adequate for smaller sailboats, but aboard larger boats, especially those with higher-torque steering demands, this system is less desirable.

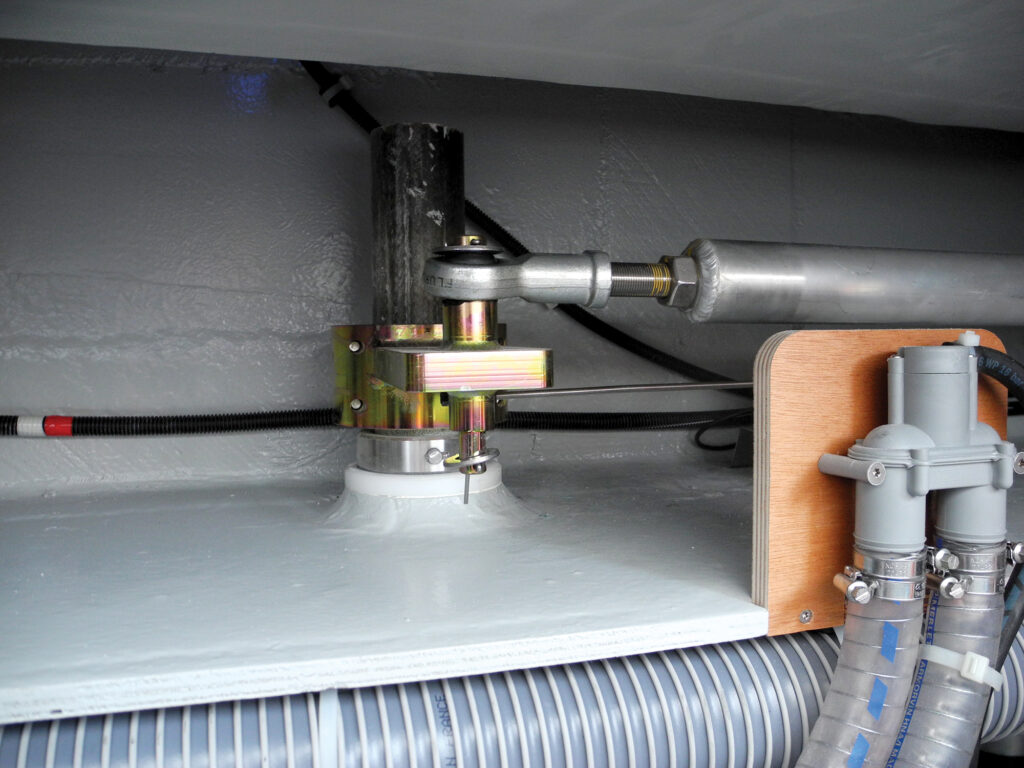

Rod- or tub-linkage steering has also become a popular way to transfer the push-pull energy needed for rudder control. But in some cases, components are hard to inspect. Many of these units have relatively small gear assemblies that reside just beneath the compass on the pedestal. These systems transmit the energy derived from turning the wheel via a gear mounted on the wheel’s spindle. A large-diameter tube runs the length of the pedestal, delivering torque to the cranklike lever at the bottom of the pedestal. Over time, the bearings that the tube relies on can corrode, and in some cases, teeth on the upper gear can break. Check your owner’s manual for the recommended maintenance.

Full-size geared systems have been around for a long time and are usually associated with rack-and-pinion gears installed in a box over the head of the rudder stock. These antique systems are seen less and less often. The steering-wheel shaft is attached to a spoked wheel on one end and the pinion gear at the other end. The rack is attached directly to the rudder stock.

A modern torque-type steering system mimics a miniaturized automotive differential unit and is capable of transmitting rotary energy from a center cockpit sailboat’s steering wheel to the rudders aft. Lewmar’s Mamba system is a good example of this type of steering.

Hydraulic steering systems are more often seen on powerboats. The steering wheel is linked to a hydraulic pump and hose system that sends hydraulic fluid to a dual-action hydraulic ram. More-complex systems incorporate a power-assist electrical pump, but these designs lack the feedback that a cable- or rod-linkage system provides and are less often seen on sailboats.

During spring commissioning, steering-system scrutiny should include a careful hunt for signs of corrosion and wear. Trace from the wheel to the rudder. Rotating the wheel should be a smooth glide from side to side. Check for wheel-spindle bushing wear (excess wobble). This is also a good time to recall when the sprocket gear and chain, or the drum and fiber cable, was last inspected. It should be done every few years or before a long passage.

Losing steering might not be as bad as losing the rudder itself. Both result in an immediate loss of control, but the steering is usually easier to remedy. A broken rudder is another story.

Next comes a close look at the wire, fiber cable, rod links, or gearboxes and torsion tubes that deliver the energy from the helmsperson to quadrants. Using a flashlight, look for signs of wear at cable turning points and linkage junctions. Jot down or voice-record indications of wear such metallic residue, excess corrosion, and broken strands in a steering cable. Slide a cotton or nylon cloth along the 7×19 SS steering cable to detect broken strands. Double-check points where the wire passes over a sheave and where it has been terminated with a thimble and Nicopress fitting, swage, or other mechanical terminal.

The rudder linkage aboard a catamaran spans nearly the full beam of the vessel. As part of an annual inspection, a crew should include full lock-to-lock steering-wheel rotation and note how the rudder linkage behaves. Check for any sign of chafe or contact with other components in the lazarettes. Aboard monohulls and multihulls alike, make sure the rudder stops are functional. They endure significant impact loads when the wheel is allowed to spin freely while powering astern. When damaged, they can allow excessive rudder angle that can be harmful to autopilot linkage and the steering system itself.

All too often, the emergency tiller remains a forgotten appendage. Its true value is most appreciated by those halfway across an ocean who discover that the steering wheel spins like a roulette wheel while the boat has a mind of its own. A worthy emergency tiller is one that can be quickly and firmly affixed to the head of the rudder stock. It allows the person steering to have a long enough tiller handle to make hours on the helm feasible.

And those with a servo pendulum self-steering vane will discover how much better their boat self-steers when the vane is connected to the tiller rather than the wheel.

Where To Start

When it comes to steering hardware, Edson had its oar in the water quite early. For more than 100 years, it has remained a key player in the manufacture of sailboat steering hardware. Its chain-and-wire system includes well-engineered idlers and sheaves. The geared CD-i solid link system also affords good feedback. Edson also offers a pull-pull twin conduit system that solves the problem of single-conduit push-pull systems. Edson designs, manufactures, and stocks top-quality components such as machined bronze quadrants, pedestals, and bulkhead mounts. Custom work includes clutched multigear steering and electronic power-assist systems that meet the needs of large cruisers and superyachts. § Lewmar offers several popular steering systems branded as Constellation, Cobra and Mamba. The first is a chain-and-cable system seen on many small to midsize cruising boats.

The Cobra system utilizes a gear-to-gear right-angle drive in the top part of the pedestal to redirect torque to the base of the pedestal. Solid linkage replaces wire cable, delivering the steering force to the lever arm attached to the rudder stock. Lewmar’s Mamba drive employs a small gearbox and reduction gear to actuate a torque tube assembly. The company also provides autopilot drive motors that have been designed as a component for each of their steering products.