Best-Case International SAR Scenario

The incoming message over our VHF radio stunned me. “Your EPIRB went off last night,” said the captain of the Chilean navy gunboat. “We canceled the search when you called Radio Wollaston. You must anchor at Caleta Martial and wait for us to inspect your vessel.”

My husband, Evans Starzinger, and I were 20 miles north of Cape Horn and motoring in light winds through the Wollaston Archipelago en route to the Horn. The night before, our 47-foot Van de Stadt Samoa, Hawk, had carried us safely through a sustained 60-knot front. When we dropped anchor in a sheltered harbor at 2300, I’d radioed the local navy station and reported our position. I knew we hadn’t activated our 406-megahertz EPIRB, but I wasn’t going to argue with a gunboat. “We’ll anchor at Caleta Martial and wait for you,” I replied.

Two hours later, the men who’d boarded us with angry scowls waved good-bye, satisfied that our EPIRB hadn’t gone off. But the two crew on a German yacht sailing nonstop from Tahiti had activated their EPIRB in that 60-knot storm. A lack of communication led search-and-rescue authorities to mistake us for them, and as a result, no search operation was launched for more than eight hours. Only the boat’s EPIRB was recovered.

Between September 1982 and late 2009, the U.S. Coast Guard estimates that EPIRBs facilitated the rescue of nearly 23,000 people, proving them to be an invaluable aid in SAR situations. But we’ve learned that activating an EPIRB is nothing like dialing 911, especially in international waters. Since our Chilean experience, we’ve been indirectly involved with two other international EPIRB incidents in which rescue efforts were hampered by communications problems, jurisdictional issues, and a lack of SAR resources. Should you ever have to activate your EPIRB, understanding how the system works, where the process can break down, what steps to take, and what those ashore can do will increase your chances of survival.

Potential Issues

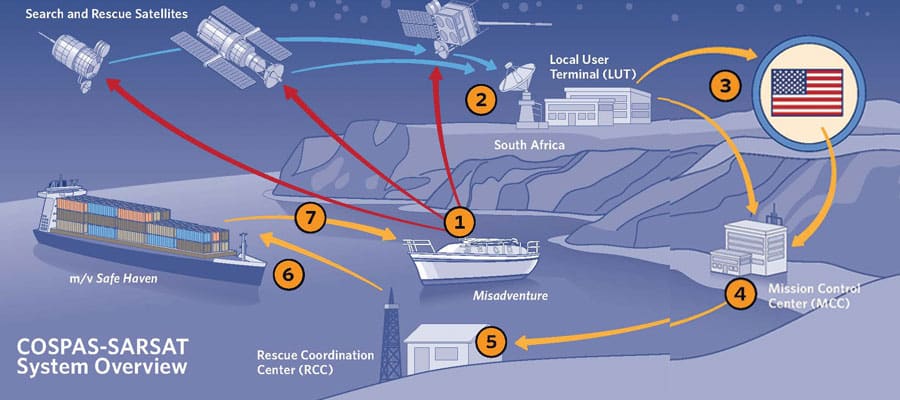

To illustrate how the system works in a best-case scenario, consider this hypothetical case, based on a composite of several actual SAR incidents.

On passage in the southern Indian Ocean from Réunion to Durban, South Africa, the sloop Misadventure is rolled and dismasted in a storm south of Madagascar. The first mate’s arm is broken. While the captain clears away the mast, the mate evaluates the situation. The batteries are dead, the engine won’t start, the electronics are fried, and the boat is taking on more water. Once the mast is addressed, the captain and first mate agree that they must issue a Mayday. The captain takes their GPS-equipped 406-megahertz EPIRB into the cockpit, where it has a clear view of the sky, and activates it at 0000 UTC at position 28 degrees south, 40 degrees east, 450 nautical miles northeast of Durban. The mate pushes the emergency button on their DSC VHF and calls Mayday on the VHF and the SSB.

The DSC signal and voice calls go unanswered, but within seconds, one of the satellites of the international COSPAS-SARSAT System (see A Glossary of SAR Acronyms and Abbreviations) detects the EPIRB signal. In this ideal example (see Best-Case International SAR Scenario), the merchant vessel Safe Haven recovers the crew within 24 hours. However, the following can increase the rescue time by days or interrupt the process altogether:

Delays in fixing the vessel’s position: Before any rescue attempt is mounted, the vessel’s general position must be established. Misadventure carries a 406-megahertz EPIRB equipped with an internal GPS that transmits position information along with the unit’s 15 hexadecimal ID number. As a result, SAR authorities know the boat’s exact location within 20 minutes—as soon as the EPIRB’s GPS establishes a fix and transmits that to the GEOSAR satellites monitoring the Indian Ocean. Had the boat carried an EPIRB without a GPS, its position couldn’t have been calculated for several hours, until a low-Earth-orbit satellite had passed over two or three times. “Initial LEOSAR positions can differ by 50 to 60 miles and sometimes cross rescue areas,” said U.S. Coast Guard Captain Dave McBride. “I’ve seen cases where the first two positions calculated by the LEOSAR have been in different oceans.”

Inability to verify the emergency signal: Today’s 406-megahertz EPIRBs must be registered in a national database, and the registration information, including vessel description and one or more emergency contacts, must be updated every two years. In the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration oversees this database, which allows SAR authorities to eliminate 85 percent of false alerts before expending any resources. In U.S. waters, an unverified emergency signal would delay a search until a position could be established, but a search would be undertaken. Elsewhere, local SAR authorities may decide not to conduct a search for an unverified signal.

Problems with cross-border coordination and lack of SAR resources: The International Maritime Organization set out rescue areas and responsibilities in the 1979 I.M.O. International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue. While the process is supposedly standard worldwide, many countries lack the resources to search for foreign sailors. In less developed countries, jurisdictional issues, a lack of resources, or communication problems can delay or prevent rescue attempts. In our example, Misadventure lies at the intersection of four rescue areas, but South Africa, the only country with SAR resources, takes the lead in the operation.

The tyranny of distance: “The challenges to a successful rescue grow exponentially with the distance from shore,” said Rick Button, chief of the Coordination Division of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Office of Search and Rescue. “Any SAR organization would be pushed to the limit of its capabilities trying to mount a rescue 400 to 500 miles offshore.” Misadventure is beyond helicopter range and at the very limit of the range of fixed-wing aircraft, so the rescue attempt is dependent upon merchant ships via AMVER, a voluntary ship-reporting system used worldwide for SAR. According to U.S. Coast Guard Lieutenant Commander Mark Turner, “Even in U.S. waters, the average time to rescue a vessel so far offshore would be three to four days. In most cases, once authorities activate the AMVER system and find a ship that can respond, it takes at least 12 to 24 hours to reach the vessel.”

Lack of critical information: A frustrating thing about an EPIRB signal is that it contains no concrete information. There’s no way to know what the exact emergency is, whether the vessel is still in distress, or even if the crew is still alive.

Difficulty in pinpointing the vessel: Captain McBride has flown dozens of missions in search of distressed vessels in the U.S. rescue area, which extends 600 nautical miles from shore. Most 406-megahertz EPIRBs also broadcast on 121.5 megahertz to assist in the final location of the vessel, but the 121.5-megahertz signal has a very short range. “I can direction find off a 406-megahertz signal from 120 miles out, but with 121.5 megahertz, I may not be able to find it until I’m five miles away,” he said. Very few commercial vessels are equipped with direction-finding equipment, so they must rely on the position supplied by the RCC. If the battery has run out and the EPIRB ceased signaling, if the boat is dismasted or awash, or if the crew has taken to the life raft or is in the water, the target may be impossible to find.

Proactive Measures

“The very worst thing is for sailors to be complacent,” Chief Button said, even after you’ve activated the EPIRB. “Assume that no one is coming, and do everything you can to rescue yourself.” Understanding the strengths and the weaknesses of the COSPAS-SARSAT System can also help you maximize your chances of rescue.

Carry the most up-to-date emergency equipment: The COSPAS-SARSAT System is a highly developed, worldwide SAR system with international protocols. But equipment and protocols change. For instance, merchant ships are no longer required to monitor earlier radio-distress frequencies; instead, they screen the new DSC system on VHF and SSB. If you’re headed offshore, outfit your boat properly with a GPS-equipped EPIRB (make sure it has a small readout showing your broadcasted position) and with both fixed and handheld DSC-capable VHF radios. Any vessel traveling to foreign ports must apply to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission for a Ship Station license, and all communications and emergency equipment aboard must be registered under a single FCC-assigned Maritime Mobile Service Identity number unique to that boat.

Register the EPIRB, and provide contacts who know your itinerary and can always be reached: International rescue may be delayed or not attempted at all if the signal can’t be verified with a contact person ashore. Register your EPIRB, and keep the information updated in the NOAA database. The site allows you to enter two contacts, which increases the chances of SAR personnel reaching a knowledgeable source in an emergency. People move and phone numbers change; make a note in your calendar to check the information on the site annually. A properly registered EPIRB carries two stickers, one from NOAA and another showing battery life and servicing.

Stay in contact with those ashore: Share a float plan, ETA, and a list of alternate ports with your shoreside contacts, and establish an emergency-communication schedule. Anything that provides position information to SAR authorities can streamline the process of verifying your location and responding to your EPIRB. While online boat tracking by the vessel- and weather-reporting service YOTREPS, Globalstar’s Spot satellite personal tracker, SailMail, and other providers is no substitute for a properly registered EPIRB, in an emergency they can provide recent position information. If you carry a satellite phone, agree on an emergency-communication plan with your contact person ashore, establishing a preset time to call if the EPIRB is activated. This will allow you to conserve your batteries but let others reach you at a fixed time each day.

Stay in contact with other sailboats in your vicinity: In offshore rallies and in the most remote corners of the world, where SAR resources are all but nonexistent, there have been many instances of cruisers assisting other cruisers in emergencies. Maintaining communications by email, satphone, or radio with those around you increases your chances of rescue.

Carry several signaling devices: Given the high percentage of false alerts, some offshore races have begun to require two emergency signals from the same location before mounting a search. Consider backing up the EPIRB with a second EPIRB or a global satellite phone with spare batteries. With a phone, you can describe the exact nature of the emergency, it works when power is lost or the boat is dismasted, and it can be taken into the life raft. Pre-program the number of the U.S. MCC (1-301-817-4576) and the RCC for the search area where you’re sailing. (Visit www.cruisingworld.com/leonard1111 for a listing of this URL and other web resources.)

Signal Mayday three ways: Rescue authorities don’t mount salvage operations. When you issue a Mayday, you’re agreeing to abandon your vessel. The Mayday should be signaled in three ways: by emergency DSC call over VHF and SSB, by a voice call over both, and by activating the EPIRB.

Increase your visibility: According to Captain McBride, “Orange sails, tarps, radar reflectors, strobe lights—when you’re searching and there’s nothing else out there, it all helps.”

Carry the best offshore life raft you can afford: I once heard a boat-show salesman claim that you only needed a coastal life raft for offshore sailing. “With an EPIRB, you’ll be rescued within 24 hours,” he said. Even in U.S. waters, you could be in the raft for several days.

Stay with the boat as long as possible, but if you board the life raft, bring the EPIRB and a handheld DSC-capable VHF: Once in the raft, you’ll be much harder to find, so making contact by other means is critical. Bring your EPIRB and handheld DSC-capable VHF, as well as the global sat phone, if you have one, in a watertight protective case. The ditch kit should also include a handheld GPS, a megawatt searchlight, flares, and, if you can afford it, a SART and a second EPIRB to employ should the batteries run down on the first. Rechargeable batteries are seldom fully charged when you need them, so choose equipment that can run on dry cells, and keep spares in the ditch kit.

Don’t turn off the EPIRB until communicating with SAR authorities: Once the EPIRB is activated, the COSPAS-SARSAT System takes over, and in many rescue areas, the process continues until the vessel is located. If you activate your EPIRB and then resolve the emergency, don’t turn it off. That will leave the authorities chasing a signal to a location from which you’ve departed, wasting resources and jeopardizing lives. Instead, if possible, update SAR organizations on your status. Otherwise, leave the EPIRB on.

Shoreside Assistance

Learning that a loved one’s EPIRB has been activated can be terrifying. But there are ways for those on shore to help, both before the fact and once you’ve been informed of the emergency. Before the sailors set out, establish a float plan and an ETA, a list of their alternate ports, and a contact schedule. If the vessel carries a sat phone, pre-establish a daily time to call if the EPIRB is activated. In addition, take these steps:

Track position reports and save any emails: Any information you can provide to SAR authorities—the onboard situation, the boat’s last known position, the relevant weather, any equipment problems, and the like—is invaluable.

Record the contact information for radio-net controllers covering the vessel’s passage area, and contact them in an emergency: In three cases with which we’re familiar, a vessel had reported problems or concerns to the net before the EPIRB was triggered, but the net controllers had no way of knowing that the EPIRB had been activated, so valuable information wasn’t communicated to the SAR authorities. If a crew has made regular contact on the radio nets, the net controller has information on their whereabouts and situation. If they haven’t, the controller will be aware of vessels in their vicinity that may be able to provide useful information or help search.

Contact (and join) Boatwatch: The organization locates lost mariners and passes urgent messages to them. Your message posted on Boatwatch is transmitted to its international network of marinas, radio controllers, and other maritime organizations.

Inform and update Internet cruising forums: In cases involving limited SAR resources, the online community has assisted families by facilitating communication with the RCC in a foreign country, providing translation services and informing local boats and the media.

Contact the U.S. embassy in the country where the RCC is located: They may be able to assist with translation or to persuade authorities to deploy assets.

Realize that the U.S. Coast Guard may be unable to assist: The U.S. Coast Guard’s assistance is limited by its available SAR assets in a given area and by its contacts with the foreign RCC. In many cases, there is little more it can do beyond providing information on the vessel’s reported position.

Two-time circumnavigator and author Beth A. Leonard wishes to thank the U.S. Coast Guard and Ron Trossbach of US Sailing’s Safety at Sea Committee for their assistance with this article.