Every so often, an aspiring seafarer will log into an internet sailing forum and ask, “Exactly what is the perfect cruising boat?” Unless they’re ‘Trolls’ looking for mischief, they usually receive a giant heap of contradictory and subjective answers, since everybody has a different idea based on various levels of experience, competence, and mostly, preference. Almost every make and model of boat is held forth by someone or other, and the waters only get muddier with each reply.

Even more elusive is defining the perfect family boat, which in addition to everything else has to be roomy enough for all the kids. Most of the cruisers we encountered on our travels who also had children had chosen catamarans—biggish ones in the forty+ foot range. There were some on monohulls, but usually pretty big ones—by our 31-foot standards.

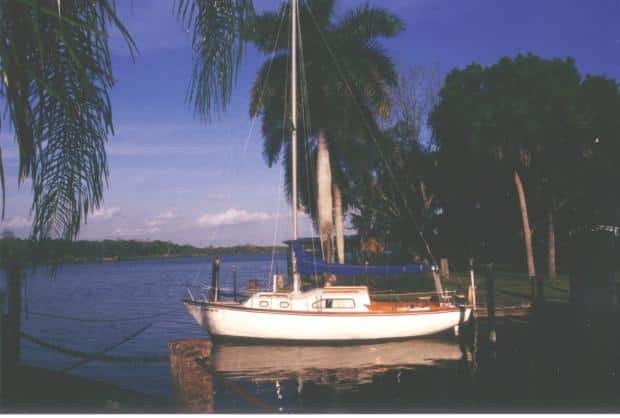

The perfect cruising boat, if you ask me, is of course our very own Ganymede. Strong, simple, easily handled—there’s nowhere that boats have gone that Danielle and I would hesitate to take her, given the chance. But there’s the thing of it—she’s the perfect cruising boat for two, but not so suited for five. Not that she’s let us down; we’ve sailed 12,000 miles in her with our three children aboard, but the tightness of quarters is becoming less than ideal.

What the aspiring seafarers really want is a formula; a rule to help sift through the bewildering array of options so they can optimize their boat search. I have come up with such a formula—one born in the crucible of nearly five years aboard in a broad range of places and situations. Here it is: You need about thirty feet for the first two people and six feet further for each additional person. So our ideal family cruising boat would be about fifty feet long.

This might have seemed laughable twenty or thirty years ago when folks generally cruised on smaller boats, but nowadays 48-foot catamarans are commonplace, 64-foot monsters like the Sundeer are seen here and there, and middle-of-the-road cruisers measure in at forty-odd feet.

Of course, hitting on a fifty-foot length was only the first step. Long night watches at sea are the perfect time to let your mind wander, and during our last cruise Danielle and I did a lot of mental sketching. The perfect family boat would of course be full-keeled, just like Ganymede, with a plumb bow and a rudder hung on a square transom. With a displacement of about 40,000 lbs, she’d be a bit much for a tiller to handle, so there would be bronze worm-gear steering. A solid bulwark all around, about eighteen iches high would be far better for keeping things aboard than lifelines, and without the frightful ugliness of netting.

Naturally, she would be rigged as a schooner—any boat over thirty-five feet should have a second mast to spread the sail area out—and even more naturally she would be gaff-headed: Bermudian rigs require so much mast height, rig tension, winches, expense and complication that they make so sense for a cruising boat. With 350 square feet of sail on the main and 250 on the foresail, each could still be easily hoisted by one person without resorting to winches. The spars would be aluminum and the standing rigging synthetic: I’ve said before that now we have Vectran and Dynex Dux, there’s no excuse for using wire rope anywhere on a boat.

In a concession to modern times and marinas that bill by the foot, the bowsprit would be easily retractable, with bobstay and shrouds tightened by cascading tackles for ease and convenience in setting up. A heavy hull with the beam carried well forward for seaworthyness and inside volume would be too large for an outboard engine, so there would have to be one inside. There is nothing worse, though, than cutting out the back end of the keel so you can drag a huge prop through the water: I would seriously look into a diesel-electric setup, with one engine powering two folding propellers, one each side of the keel, or two smaller diesels, maybe 20-ish HP each. Either way, the engine room, placed aft under a 10X8 foot pilothouse, would be hermetically sealed from the rest of the boat. Any through-hulls would be placed there, to minimize the risk of sinking, and there would be another collision bulkhead forward, dividing an ample sail/chain/tool/utility locker from the living area of the boat, just like Ganymede has.

We sketched it out one day on graph paper, just to see if everything we wanted could be made to fit. It helps to have built one boat already and know just how big things really need to be, and how much headroom is desirable, and what width of door it’s nice to have. It took a couple of tries, but we managed it in the end: one master cabin, three smaller ones, two heads, table for six, galley, woodstove, full-sized chart table, plenty of locker space: the ultimate family cruising boat, Zartman style, and with room to carry the children into their teens.

“Could we?” we wondered, thinking of the breathtaking huge-ness that project would involve; thinking of the astronomical cost of time and materials, not to mention a veritable Gordian Knot of logistics. Lots of things had come together most fortuitously to allow us to build Ganymede. A rent-free place to build her; an evening job that allowed mornings to be devoted to boatbuilding, an almost manic motivation to get back to seafaring as quickly as possible. It seems highly unlikely that all the necessary circumstances could come together a second time for a far more ambitious project.

Still, Ganymede started with a crazy idea, an idea that seemed foolish and unlikely and even impossible at times, yet here we are. Most likely this vague schooner thing will forever remain in my mental filing cabinet as something I’d like to do someday, just like sailing the Northeast Passage over the coast of Siberia, or digging a cave-house into the side of a hill, or adapting carbide miner’s lamps to replace the kerosene lighting on Ganymede. Most likely, but you never know. You simply never know.