The inevitable may be delayed but never denied. After a 22,000-mile Pacific Rim tour and two years of wanton neglect of our steel cutter, Roger Henry, I was finally forced to face the haulout from hell.

It is often said in regard to boat projects that one should make a generous estimate of the time and money required and then double it. I have been working on sailboats for a very long time, and yet I still allowed hope to triumph over experience. I would eventually triple and then quadruple that estimate before my project was done.

But ignorance is bliss, and I charged into the refit with energy and enthusiasm. As a symbolic gesture of my focus and commitment, I told my wife, Diana, that I was not going to shave until the day we relaunched. It was about the time that the yard workers started referring to me as Brother Jebediah that I realized I had become lost in a fog of rust, dust, wood chips and paint splatter.

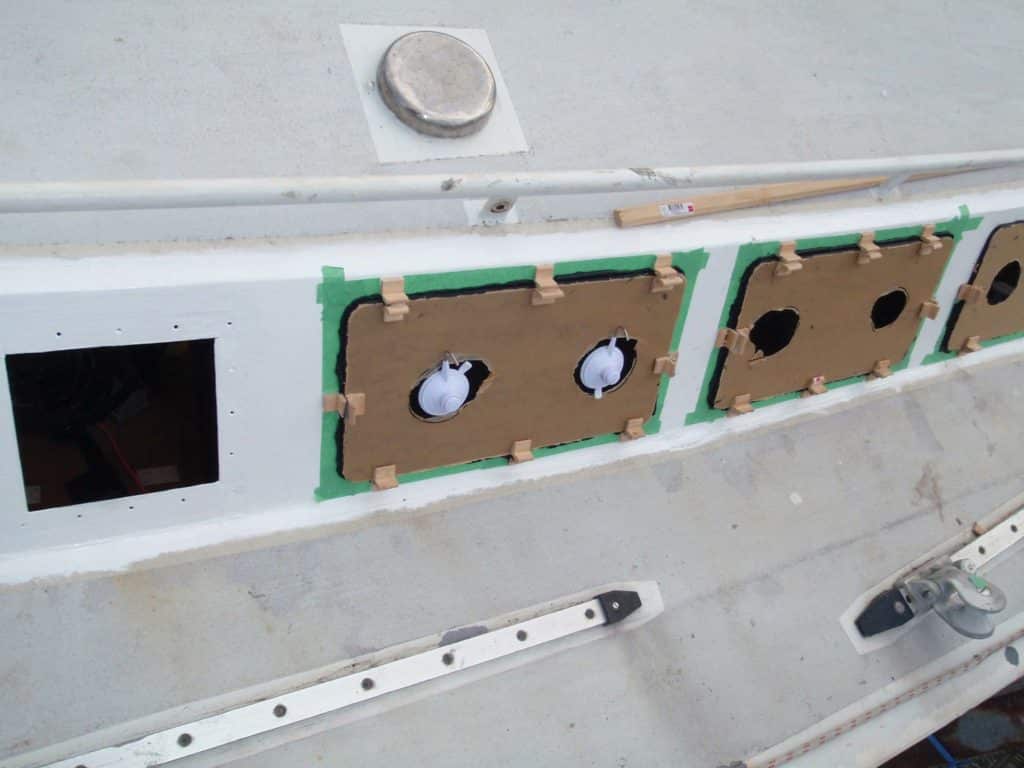

My work list was long, but initially achievable. However, every job I started led to another — the theory being “Well, as long as I have this open, I really should tend to that.” Such logic soon led me past the already ambitious schedule of sandblasting the bottom and painting the topsides and deck, changing out all the deadlights, replacing the toerails and installing new hatches.

An adage of war is that the bullet you don’t see is the one that gets you. It’s the same with a steel boat. It’s where you cannot see that the dreaded danger lies. In the process of tearing out the interior lining and sills behind the 11 deadlights in my main saloon and aft cabins, I found an alarmingly thick scale of rust. I boldly probed further, at first determined to follow the carbon cancer wherever it led. But as it disappeared behind lovely wooden cabinetry, the kind that only a crowbar can remove, I lost my courage and turned back.

I felt less the coward when I read that high-carbon steel can produce multiple layers of rust scale, much like a phyllo pastry, that, for as thick as they appear, may only constitute one-quarter to one-eighth of the host material. I calculated the thickness of the original plating, and felt that I had many years and miles before oxidation became more than a cosmetic concern.

Days later, when sandblasting the bottom, I noticed some strange little discolorations in the otherwise clean white steel. I picked away at them with my chipping hammer, exposing what appeared to be small black nuggets embedded in the steel. I gave one a mighty thump with the sharp chipper and almost fainted when it tore through the supposedly thick steel, creating a gash as ugly as a chainsaw wound. With a piece of chalk in hand, I scrutinized every square inch of the hull, finding and circling seven such pittings. All occurred at or below the waterline running along the exact lines of the interior stringers. Those stringers had been silently and secretly collecting little splashes of salt water for over 30 years.

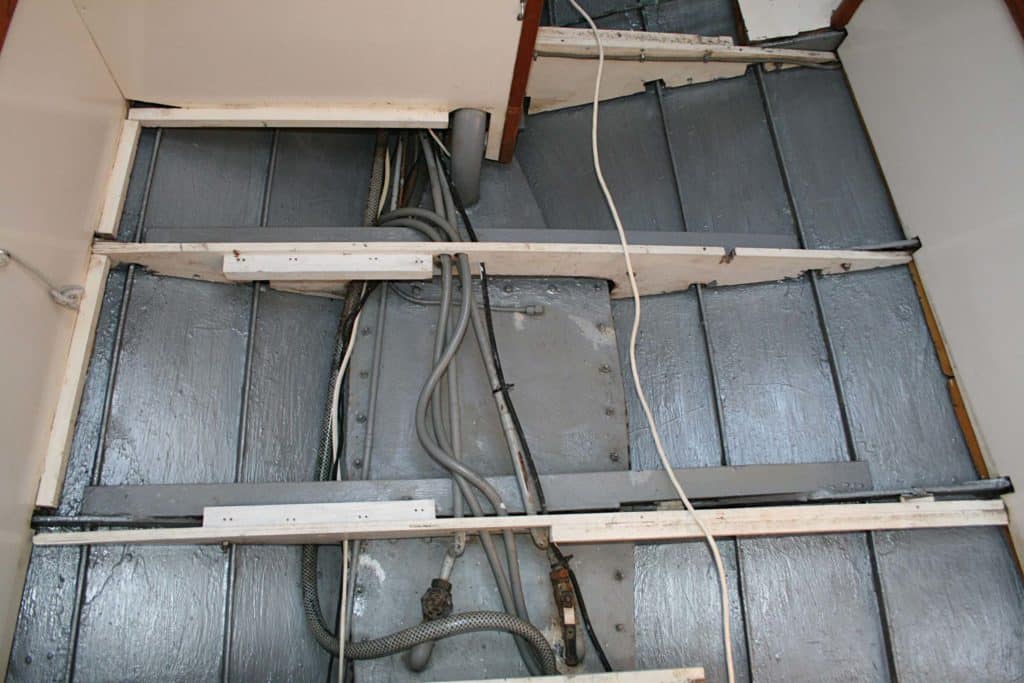

I still find it hard to speak of the atrocities I was forced to commit to gain access to the interior of the hull, for steel boats rot from the inside out. And I can only hope that the memories of the following months of chipping, cutting, welding, grinding and painting will fade in time.

I quit going home at night, allowing me to work later and start earlier. I tried to keep some control over the chaos of torn wood and dangling wires, but when the interior ceiling fell down on my head as I was trying to cook a proper dinner, I realized that it was futile.

I hermetically sealed off one small berth, and nightly crawled into it for some sanctuary. But even that had to be abandoned when I started phosphoric acid washing and epoxy painting the bilges.

Some of the contorted positions I was forced into to chip and paint — for example, underneath the marine sanitation device — were as undignified as they were difficult for a man of advancing years. But I forged on and on, January fading into February, then March, then April. Diana once gave me a whiskey flask for my birthday with the inscription, “God does not deduct from a man’s allotted life span the time that he spends fishing.” By late May I pondered that if this saying applied to boat work, I might achieve immortality.

Diana abandoned the home and garden and jumped into the fray. There’s something about a girl in coveralls. As for friends, under normal circumstances I try to be as gracious as I am gregarious, but if someone dropped by for a chat, I asked them to either pick up a tool or leave. The saying that “time is money” aptly applies to one’s yard bill; the calendar and calculator tick to the same beat.

The old deadlights had been mechanically fastened with a ridiculous number of nuts and bolts. I decided to follow the modern trend of simply gluing the new acrylic onto the outside of the trunk cabin with a structural glazing sealant. I thought, “How difficult could it be?” A week later I had my answer: very. When wet, the bedding compound acted more like a lubricant than an adhesive. I had to apply enough pressure to the deadlight to bend it around the curvature of the cabin. But because the acrylic rectangle was not retained in a recessed sill, no matter how directly I tried to apply force with my jig, the pressure forced the deadlight to slide off center, creating an unholy smear of dripping goo. Through trial and too much error, I eventually employed a system of tabbing, glued to the steel beside the deadlight, that acted as a retaining guide.

A friend helped me scarf up 35-foot lengths of hardwood toe rail, which I thought was the lion’s share of the work. Four days later I was still struggling with their installation.

I decided to spray paint rather than roll the bottom to achieve an even thickness of 400 microns of epoxy paint via two coats, followed by two heavy coats of ablative antifouling. The topside paint consisted of two coats of high-build epoxy primer and then a hard polyurethane topcoat. Making too smooth a job of it would only highlight the imperfections in the hull caused by a torturous year in the high Arctic ice, so we chose the rough-rolled “orange peel” look to break up the gloss.

Then we moved on to the decks. In spite of the durability of epoxy paint, it chalks, fades and cracks when exposed to ultraviolet light. Thus we had to cover the epoxy with a two-part polyurethane. For nonskid we used a one-pot acrylic paint as thick as yogurt, and applied it by brush. Then the paint was textured with a textured roller that resembles hard cotton candy. Depending on the number of passes of the roller, one can create a soft or aggressive nonskid surface. This is the easiest and most durable system I’ve ever used, with the advantage of easy touch-up and water cleanup.

The garbage bin overflowed with mixing cups, hardened rollers and paintbrushes, and empty cans of exotic paints worth their weight in gold. One month, my yard bill was such that I was certain they had misplaced the decimal point.

The windlass had to come out for servicing, meaning the forepeak, that one small area of the boat as of yet undisturbed, had to be torn apart. The sandblasting required the removal of the old through-hull valves and skin fitting. After careful inspection, I replaced those that showed any signs of wear.

“Hmm, the old bilge pump hose still has some life in it, but do I really want to tear all this up in five years to replace it? Well then …”

My body was giving out, but my mind became more of a worry. I found myself staring into space, forgetting why I had just come up the ladder. Then remembering the moment I hit the bottom rung.

I started the reconstruction of the interior. Each deadlight box sill had to be shaped into the compound curves of the trunk cabin. That required more fittings than a wedding dress. Because I abandoned the mechanical fasteners I was forced to jury-rig complicated jigs to hold the sill in place until the adhesive set.

I laid in a woven polyester insulation between the freshly epoxy-painted frames and stringers, then lined the hull with a thin sheeting of smoothly painted plywood. Then every sill, corner and cabinet had to be trimmed out. A typical house on land is a coalition of 90-degree angles resulting in a sensible symmetry. Whereas the typical boat, as elegant as it may be, is a cacophony of compound curves and confusing angles. The difference between an amateur and a professional carpenter is not necessarily found in the end quality of a job, but in the time spent on it. As the days rolled on, there was no question as to which I was.

In a panic about the money and time consumed, I was tempted to cut corners. I opined, “This rule of thumb about re-rigging your boat every 10 years or 20,000 miles is just another con to get more money out of us. It’s stainless steel. It’s inert! This rig will be standing long after the Golden Gate Bridge falls.”

Nevertheless, I eventually forced myself to disassemble it all anyway and perform a meticulous inspection. I felt a dread in my stomach when I took off the little retaining disc at the top of my headsail furler. Hidden beneath were several broken strands of the single most important piece of equipment on any sailing vessel: the headstay. I shuddered to think that I almost rationalized my way out of this fundamental process of sound seamanship. Although I did not appreciate it at the time, I suspect that when I am next being swept stem to stern with angry graybeards, I will not be reflecting on the cost of my new rig, but rather its uncompromised strength and safety.

I realize that, to this point, I have recorded my experience as a tale of woe, a litany of gripes and groans. That is because, when overwhelmed by the immensity of the project, I lost sight of the forest for the trees. But seven months from the day a bearded and bleeding old steel boat rumbled up the slipway, I absolutely beamed with pride and satisfaction to see our beloved Roger Henry gracefully slip back in to the sacred waters of the Pacific, gleaming in the sun all shipshape and Bristol fashion.

I have come to believe that we do not actually own our vessels. Rather we are stewards of these crafts, charged with the responsibility of keeping them safe and sound while under our care. But this is a reciprocal agreement. The Roger Henry has been my hearth and home for nearly three decades and has carried Diana and me safely on all the adventures that have shaped and even defined our lives. I was wrong to think about any single component of my boat as inert. For in aggregate these parts become a living thing, almost a member of the family, and for the bluewater sailor, as they go, so go our dreams.

This article first appeared in the April 2014 issue of Cruising World. Alvah and Diana Simon are presently cruising the North Island of New Zealand aboard their 36-foot cutter, Roger Henry.

Steel Cutter Roger Henry