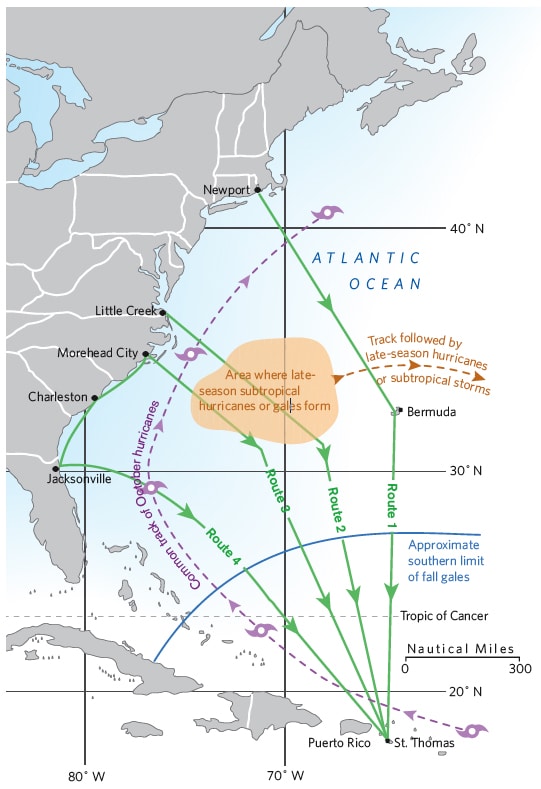

Going south in late fall from such New England ports as Newport, Rhode Island, by way of Bermuda is basically playing Russian roulette. In 2011, the bullet ended up in the firing chamber, and as a result, two boats and one life were lost. (See “Hard Lessons Learned in the North Atlantic,” February 2012.) This has happened many times in the past, and it will happen again if sailors keep following that same route. The North Atlantic is no place for a cruising boat with a shorthanded crew when fall gales rile the sea.

My first trip to Bermuda was in the 1954 Newport-Bermuda Race, and I’ve been back to the island several times since. Dozens of times I’ve gone south to the islands from the U.S. East Coast, but only once, in 1960, when I was young, foolish, and overconfident, did I sail south via Bermuda. All other trips jumped off from Morehead City and Beaufort, in North Carolina. I’ve been following news of the fall southern exodus to the Caribbean for 57 years. While some years saw two or three boats lost, and other years, none, I’ll say with confidence that the long-term average over the past 57 years is one boat lost every year. As to lives lost, I gave up counting about 30 years ago when my 29th friend or acquaintance was lost while bound for Bermuda. Joshua Slocum, the first man to sail around the world singlehanded, was lost at sea in November 1909 while en route to the eastern Caribbean. His great nephew, Bret Slocum, died in Tropical Storm Gilda in 1973 while en route to the islands. It should be noted that in the last 20 years, more November and December hurricanes have been recorded than altogether in the previous 120 years.

Now with EPIRBs, good life rafts, long-range helicopters, and ships that can be contacted to aid or take crew off sinking boats, the human casualty rate has gone down—but deaths still happen. When the weather turns, waves get in sync, so if their heights are running 20 feet, you must periodically expect rogue waves of 40 feet. That’s why in heavy-weather conditions, all crew must clip onto safety lines before they come out of the hatch and stay clipped on until they’re back in the companionway. And while a good boat and an experienced, tough crew of four on board can make the handling of 40-knot fall blows possible, the smart skipper should anticipate worse and try to plan voyages to reduce to a minimum any chance of getting caught in areas where gales of over 40 knots can be expected.

Sailors heading south to Bermuda in November should stop asking for weather windows, and weather routers should stop providing them: These windows don’t exist except for 90-foot sailing rocket ships that can reach Bermuda in three days. U.S. East Coast weather becomes so unstable in November that forecasts are good only up to 48 to 60 hours.

In September 1964, Yachting published “Going South,” the first of probably 300 articles that I’ve written. I recommended going to Bermuda in September, when the weather is relatively stable, leaving the boat there, then flying back to Bermuda in December to continue the trip south from there. For November departures, I recommended setting sail from Morehead City. From there, I said to head east-southeast until the butter melts and the trades fill in, typically between 66 degrees and 65 degrees west, then head south. That article is still correct today, and if sailors had followed that advice, it would’ve saved untold lives and saved the underwriters a lot of money.

An alternative for boats unable to pass under the bridges along the Intracoastal Waterway is to jump off from Little Creek, Virginia, just inside the mouth of the Chesapeake. Wait there for a weather window that will enable you to cross the Gulf Stream, then follow the same east-southeast course, forgetting about Bermuda. The 350-mile cruise from Newport to Little Creek can be done direct in two to three days sailing offshore, or you can take about five days and go inshore via Long Island Sound, through New York, down the New Jersey shore, then tuck inside and sail down the Chesapeake to Little Creek. Either way, it’s a good shakedown for boat and crew; any deficiencies in either can be rectified before the final jump off.

From Little Creek to St. Thomas, in the U.S. Virgin Islands, the sailing distance is about 1,380 miles and will take eight to 11 days, depending on weather and boat. From Morehead and Beaufort, the trip should take about the same time. The great advantage of setting off from Morehead is the fact that you’re in the Gulf Stream and out the other side in 24 to 30 hours. You’re also below the worst of the North Atlantic’s gale area. My Imray-Iolaire Chart 100 covers this route and includes weather and routing information.

Newport to the islands by these routes is faster in total time and less expensive than via Bermuda. Money in Bermuda disappears as fast as an ice cube on a blacktop road at high noon in the tropics! Plus, by avoiding Bermuda, there’s no chance of your crew jumping ship, an all-too-common occurrence after a rough sail from Newport.

Should you be delayed in Morehead/Beaufort by continual gales, one option is to continue along the I.C.W. to Charleston, South Carolina, a three-day voyage.

This puts you farther away from St. Thomas than from Morehead, and the Gulf Stream is well offshore and too far for a reliable weather window. Instead, head south inside the Stream, where you’ll find either no current or possibly a small countercurrent helping you as you make your way to about Jacksonville, Florida. Near Jacksonville, the Stream is close to shore and quite narrow, and you can cross it and be out the other side in 24 to 36 hours.

Then follow the sailing directions given to me in 1956 by the late Bob Crytzer, who’d been a captain in the U.S. Navy and was the man who sold me Iolaire for $3,000 down and $1,000 a year for four years, with no interest and no repossession clause: “Wait until a norther is predicted, and take off 24 to 36 hours before it arrives. This will get you across the Stream. Shorten sail before the norther hits and ride it eastward. As the norther dies out and the easterly fills in, it’s hard on the wind on port tack. Then see where you make your landfall, at either St. Thomas, the eastern end of Puerto Rico and the Spanish Virgin Islands, or the western end of Puerto Rico.”

This trip can be done in nine to 11 days. If you end up reaching only the western end of Puerto Rico, all is still well. Go to Puerto Real, to the Marina Pescaderia, where you can arrange to clear Puerto Rican customs. After some R&R, head eastward along the south coast of Puerto Rico, taking advantage of the land and sea breeze as I explain in my book Puerto Rico, the Spanish, U.S., and British Virgin Islands, the only guide that covers the region in a single volume. You may enjoy the south coast of Puerto Rico and the Spanish Virgin Islands so much that you’ll be in no hurry to reach the British Virgin Islands after all.

Don Street’s cruising guides and Imray-Iolaire charts are indispensable to the Caribbean-bound cruiser.