Cap’n Fatty Goodlander

Anchored off Nukualofa, Tonga, we were attempting to figure out what delicious thing to do after lunch. That’s a reoccurring problem for us. We sincerely want to treat ourselves a little bit better every day—which isn’t easy, after a lifetime adrift from the Corporate Clock. We have no schedule, no boss, no job. Each second we live is entirely our own—to cherish or squander. My buddy Webb Chiles says we sailors are “artists of the wind.” I like that lofty, slightly daft concept. It makes me grin. But my ultimate focus is more on cruising than sailing. So perhaps I’m an artist of time.

“What’s on the menu for this afternoon?” says my wife, Carolyn, with a yawn. “Should we be good little sailors and restitch the headsail sun cover or head ashore for some decadence?”

“Decadence, definitely,” I said. “Better yet, let’s get artsy-fartsy!”

She grinned. She was into it. “I’ll get my hat,” she said happily.

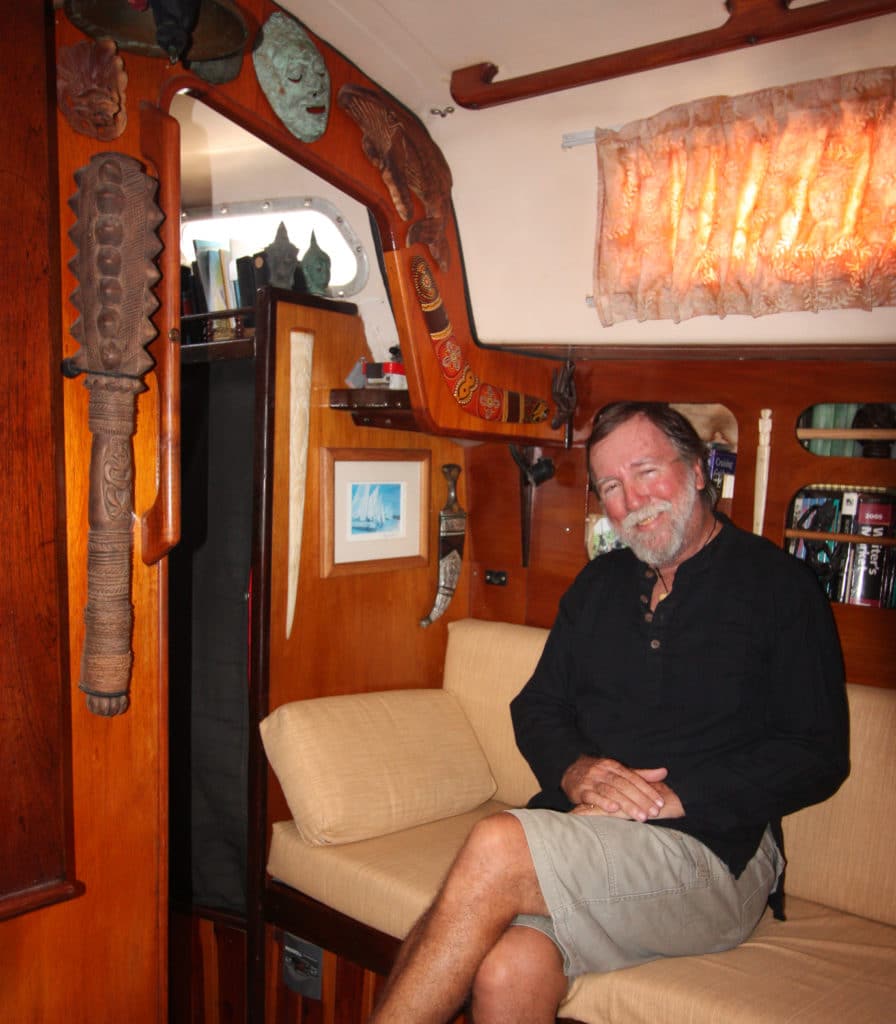

With 10 feet of beam and weighing 13,000 pounds empty, Wild Card is a small, relatively light 38-foot vessel. There’s barely room for us. Most of what we have aboard are tools, a term I use in the broadest sense: My computer, Carolyn’s bike, and our life raft are all tools in one form or another. And we’re not terribly material people. My subscription to GQ lapsed years ago. Carolyn spends more time poring over the Budget Marine catalog than flipping the pages of Vogue. But there’s one thing we do collect as we go: local art.

Admittedly, we’re not like the Mellons, buying million-dollar paintings and donating them to the National Gallery of Art, in our nation’s capital. We’re a bit more casual and laid-back. We often buy items in the $5 to $10 range. We’re fuzzy with the line between art and craft—who cares, really, if the piece emotionally touches you? Our gallery is small. It consists of the main bulkhead of our boat. Our collection rotates. Some items have been on display for a decade; a few only last a week or two before being brought down in disgrace.

Art isn’t straightforward. Neither is collecting it. We like to meet the artist and see where he or she works. Often, the studio is the shaded area beneath a palm tree. Many have a single tool: an old pocketknife, or a battered paintbrush. I enjoy woodworking, so it’s only natural that I’m particularly interested in woodcarvings.

We don’t really have a clue what we’re doing. We haven’t formalized our collection or locked ourselves into any single concept. Carolyn loves to buy me opium pipes. I dig knives and swords. But we’re open to anything. I’m enthralled with our death masks from Papua New Guinea; our cannibal fork from Fiji; our carved marlinspikes from Niuatoputapu.

Weapons are interesting: Every tiny dot means something to the chalk-dusted Aborigine who carved my outback boomerang.

In Tonga’s Ha’apai Group, we came across a weather-bound fishing vessel whose ancient skipper made carvings upon the swords of the swordfish he caught. I asked him about the mystical figures dancing within.

“This is a swordfish, and this is a sailfish, and this is an alpha male,” he said without a blink. I thought to myself, where did he get “alpha male” from?

“Beautiful,” I said.

“Twenty bucks,” he said.

“Would you consider $20, a small sack of rice, and a warm six-pack of beer?” I counter-offered.

“Twist my arm,” he said in agreement.

The more primitive the art, the better. I particularly enjoy our African carvings, representations of strange, tall people with oddly misshaped features and twisted skulls carved in ebony by nearly mute jungle folk who look exactly that way.

One piece I purchased from the animists of Indonesia was so powerful that I couldn’t keep it on the bulkhead. I’m not sure how to describe it; that it gave off an “invisible heat” is the best I can do. I took it down almost immediately. But it screamed out to me from the bilge, too. I eventually had to send it to the most powerful spiritual person I know in America, who now keeps it under three mattresses in the basement.

Art has power. Why else would sensible people pay millions for some paint-smeared canvas in a wooden frame?

Culture plays an important part. The Thais are in search of tranquillity, hence their Buddha is serene. The Chinese, on the other hand, were scared and starving to death; hence their Buddha is fat and happy.

Perhaps part of my obsession with art stems from the fact that my father was a commercial artist and sign painter by trade, and both my sisters have sold many of their paintings. My sister Gale, in fact, is married to James A. Whitbeck, a New England artist. Me? I can’t draw a bath.

I guess the point I’m trying to make with all of the above is that sailing the world isn’t just about sailing the world; it’s about living and loving it as you do so.

Carolyn and I are richer in time than even the Mellons, so why shouldn’t we spend a bit of it as they do? The joy we receive while doing so far outweighs the slight monetary costs.

Good artists are often generous in their praise of other artists. One thing often leads to another. So we adjust our whimsical course accordingly and thus meet the tattooist of Moorea, the pearl carver of Makemo, the basket weaver of Vava’u.

“Why are you here?” asked a maker of traditional fishing lures on a tiny island in the vast Pacific Ocean.

“Because you are,” we replied. “We heard about you in Tahiti. We viewed some of your work there. It was only a couple of hundred miles out of our way, so we thought we’d drop by, and we’re happy we did.”

If we didn’t collect art, we’d never have realized that the State of Yap in Micronesia is the only place in the Pacific that’s head-over-heels in love with macramé. Why? We still haven’t puzzled that out, although we’ve been asking for years.

But on this particular day in Tonga, we climbed the hot stairs above the teeming Nuku’alofa market and chatted with our favorite local carver once again. I was attempting to resist his pièce de résistance, a magnificently carved Tongan war club. It was too expensive and too heavy. I couldn’t possibly.

Then he pointed out the strange little Polynesian guy doing a haka on the shaft and the fact that the string on the handle grip wasn’t commercially made; it was woven locally out of coconut-husk fibers.

Gosh, it was lovely.

I looked over at Carolyn. She smiled her agreement and encouragement. We walked out US$88 lighter, but with the war club tossed casually over one happy shoulder.

The moment that we returned to Wild Card, I gave it pride of place on the bulkhead.

“Happy now?” Carolyn asked.

“Yes, very happy,” I smiled. “And I’ll never forget today. The French are right, the word souvenir really does mean ‘memory.’”

Cap’n Fatty Goodlander’s latest book, Red Sea Run: Two Sailors in a Sea of Trouble, is now available from Amazon.com.