Towing with a tender

Although the modern marine engine has become very reliable, at some inopportune time, as with all mechanical devices, it may fail. Or you may find yourself in a position to help another sailor whose boat is disabled. Or you may find yourself becalmed in a less-than-ideal situation. Becoming proficient at the three primary towing configurations here will give you confidence that you can safely and efficiently handle these situations.

Much can be learned from professional seamen. Many of the finest boathandlers in the world are tugboat captains. The scale is different, but the techniques that they’ve developed for moving ships and barges are the same ones that cruising sailors use for towing and docking disabled boats.

Most sailboats today carry inflatable tenders with outboard motors of reasonable power to move the boat. A 10-foot inflatable tender with an 8-horsepower motor can easily maneuver a 50-foot boat in moderate conditions. In calm conditions, much less power will do the job. The first step is to have your tender, whether it’s a small inflatable or a hard dinghy, set up for the task. Inflatable tenders should be at their maximum recommended pressure. On our 11-foot inflatable RIB tender, we have 18 feet of 1/2-inch braided nylon for the bow line, several 12-foot lengths of 1/2-inch braided nylon that can be used as spring lines, a 5/8-inch braided nylon towing bridle with a stainless-steel snap on one end, and 100 feet of 5/8-inch braided nylon for the towline. The size and strength of the lines depend on the size and horsepower of the tender. Braided nylon makes a good choice because of its superior combination of strength, stretch, and chafe resistance. We also carry on board a sharp sheath knife should a line need to be cut in an emergency.

If the need arises (and it has), we can quickly hitch up and move a boat using any of these three configurations. When pushing or towing, always wear a life vest, preferably a work or sport style that’s comfortable and doesn’t inhibit movement.

The Side Tow, or On the Hip

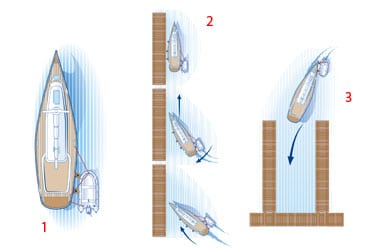

The best method for short tows in calm to moderate conditions where you’ll be docking the boat and are unlikely to encounter large wakes from passing vessels is the side tow, known in the commercial world as “on the hip.” First decide which side of the boat you’ll put next to the dock, then hitch up on the other side. Set up fenders for the tender; secure them alongside as shown in Diagram 1. The tender should be as far aft as the boat’s shape allows.

Sailboats with long stern overhangs won’t allow you to hitch up as far aft, but if the tender’s motor is aft of the boat’s rudder, maneuverability will be adequate. Double-enders tow well on the hip as the tender is able to push nearer to the boat’s centerline. On the hip doesn’t work well with catamarans.

Lines should be snug and secured properly to cleats in such a way that they won’t bind. It’s very important to be able to release lines in a hurry if a large wake should approach or you need to rapidly reconfigure. If towing in limited visibility or where other boats may be operating, give a sécurité call on VHF 16 with your description, location, and intended course. The last thing you want to encounter is a big sport-fishing boat roaring by unaware of your situation. As you begin towing, be aware that because you’re off center, extreme leeway will develop. The helmsman will need to crab the boat to make good on your desired course. As a reasonable speed is attained, the boat’s underbody will get a better “grip” on the water, and holding course will become less difficult. Until close-in maneuvering is required, steering should be done with the boat. Oversteering with the tender will make holding a course difficult. If the tow is configured as in Diagram 1, rapid turns can easily be made to port. Turning to starboard will be much slower and have a large turning radius. If a rapid turn to starboard is required, put the tender in neutral or even in reverse, allowing the boat’s momentum to carry it through the turn. This ability to crab the boat will greatly facilitate coming dockside. The key is to plan ahead and to get a feeling for the boat’s forward momentum and your ability to control and stop it. Always “test the brakes” prior to docking. Approach the dock (see Diagram 2) at an angle of between 30 and 45 degrees, keeping the bow pointed at the midpoint of the space on the dock where you want to end up. You should maintain only enough speed for steerage. Just before the bow of the boat reaches the dock, put the tender in reverse. As the boat continues to slow and stop, the bow moves out and the stern pivots in. This is a very satisfying maneuver when done properly. If you have to back the boat into a slip, reconfigure as in Diagram 3. If docking in a strong current, always plan your approach and final maneuver so that you’re pushing into the current. It can be used to your advantage when crabbing into a tight spot.

Pushing from Astern

Pushing from astern is my preferred method for covering longer distances in moderate conditions when good control is required, as in a waterway or a harbor’s entrance channel. In Maine’s Penobscot Bay, many of the passenger schooners have no engines. The crew rely on their tenders, or yawlboats, to push them in and out of the harbor in calm conditions. They have become very skilled at handling these large and beautiful vessels in this manner.

Pushing the boat from astern, as in Diagram 4, is efficient because you’re pushing from the boat’s centerline, eliminating the need to crab. Depending on what type of stern your boat has, this method can be used in rougher conditions than the side tow. Some sailboats have extreme reverse or scoop transoms that make pushing awkward. Self-steering gear, boarding ladders, and stern-hung rudders can also preclude this method. It does work well for most boats, however.

As in all hitch-ups, ensure that lines are secured in a way that can easily and rapidly be unhitched or adjusted. The spring lines must be tight and well secured, as they carry a lot of strain when turning. The unexpected release of one of these lines when turning poses a danger to the tender operator, as the tender will quickly scoot to one side, possibly tripping and throwing the skipper overboard. Pushing should be steady, with the outboard centered. Most motors have steering dampers that can easily be adjusted. It’s worth setting it so that the motor doesn’t swing easily on its own.

As catamarans usually have twin engines, it’s less likely that you’ll ever need to tow a cat. But they can be pushed quite easily. (See Diagram 5.) It’s extremely important when pushing a cat to have the two bow push lines in good condition and well secured. The tender’s bow line acts as one of the lines. The other is attached to the same bow eye as the bow line. The lines should be attached as far aft as possible on the cat’s hulls. If one of these lines lets go when you’re pushing hard, the tender will scoot ahead under the stern deck, with a high likelihood of injury to the operator.

When pushing from astern or on the hip, if you have to stop the boat or maneuver quickly to avoid an obstacle faster than the boat’s forward momentum allows, use hard reverse and pivot the boat while the helmsman holds the rudder in opposition. The rapid turn will quickly slow and eventually stop the boat’s forward carry.

Towing Astern

Towing astern is the preferred method for longer tows, rougher conditions, or times when occasional large wakes may be encountered. This method requires the highest degree of skill, and it’s also perhaps the most dangerous if done improperly.

Good planning ahead of time with your crew is imperative, as communications won’t be as easy as they are when using the other methods. When towing, you won’t have a good line of sight to the helmsman, and the sound of the motor makes hearing difficult. Arrange some easily understood hand signals for stopping, slowing down, speeding up, change of direction, and the like. A handheld radio is helpful. Have the helmsman steer for the stern of the tender.

If the towed boat steers erratically or turns off in a different direction, it’ll cause the tender to go off course. In extreme cases, it can cause the tender to be overrun by the boat’s momentum as the tender struggles to stay in front or is swept alongside and aft, then swung stern-to as the boat surges ahead and the towline takes up.

When preparing to take the boat in tow, first rig your towing bridle. (See Diagram 6.) I clip the bridle on one transom eye, then run the line aft of the motor, securely attach my towline, then tie the bridle to the other eye. The bridle should be short enough to keep clear of the tender’s propeller but long enough to keep it clear of the motor. When the towline is centered and under load, it should form close to a 90-degree angle. I make sure that my towline is in several smaller coils and able to run free. Usually it’s best to approach the boat’s bow from leeward, then pass or toss the towline to the crew. I usually keep the bulk of the coil with me to lessen the risk of a foredeck tangle. Once the line is secure, maneuver ahead slowly and toss the remaining line astern.

As long as you’re moving forward, the line will stay clear of the tender’s propeller. As the slack comes out, ease ahead until the line grows taut. Depending on the conditions, I’d deploy 50 to 75 feet of towline to start. Gradually increase speed, and have the person on the bow adjust the towline so that the boats are in step, that is, both in the trough of the seas at the same time.

Towing out of step puts intermittent strain on the towline, as one boat surges down a wave while the other boat slows down climbing one. Having the towline properly secured is very important. If it comes loose or breaks a cleat, the loose end will slingshot toward the tender. The crew on the boat needs to keep an eye on the towline for signs of chafe and to ensure that the line remains secure.

Tugboats and purpose-built towboats are set up with towing bitts located forward of their rudders. This allows them to turn “under the tow” and maneuver. This can’t be done in a small inflatable, as the outboard motor is in the way. Attempting to tow from forward of the motor risks that the towline will catch on the motor’s cables and controls.

A technique that I’ve used when towing with boats that lack towing bitts or have outboards in the way involves using a sliding bridle. (See Diagram 7.) Anyone who’s attempted to tow a boat from off center knows that the towboat will rapidly be pulled sideways, and any attempt to get out in front means slacking the towline, trying to avoid getting it caught in the propeller, and starting over. With the sliding-bridle method, you attach the towline to a smooth stainless-steel ring or a seized shackle that can freely slide from side to side on the bridle. If one isn’t available, simply tie a bowline onto the bridle. When you first take a strain, the towline will go to center. Let’s say that you want to turn to port. Ease off on the throttle, but not so much that the line goes completely slack. Turn hard to port. As the tender’s stern goes to starboard, the towline slides to port. Take up the strain; when the tender is in the desired position and the towed boat is on the desired course, ease off, turn slightly to starboard, and throttle up to center the towline. This method served me well for many years when towing boats and floats at my boatyard.

In conclusion, I want to emphasize the importance of preparing and planning ahead for any of these maneuvers. Know the capabilities of the crew and tender, and take the time to practice. Good boathandling is a sign of good seamanship.

_

Captain Earl MacKenzie, who holds a 500-ton Ocean Master license for power and sail, and his wife, Bonnie, run and operate_ Bonnie Lynn_, a U.S. Coast Guard-inspected brigantine rated for ocean service. To learn more about the MacKenzies, see “Bonnie Lynn: A Dream in Fast-Forward” (August 2000)._