Modern boat electronics provide a great benefit to sailors when it comes to navigation, weather, collision avoidance or just the plain fun of being under sail. So it’s no surprise that we cruisers regularly add to our gadget list, often mixing brands and coupling old with new. Often this raises compatibility issues, some of which lead to creative work-arounds and others to outright failure.

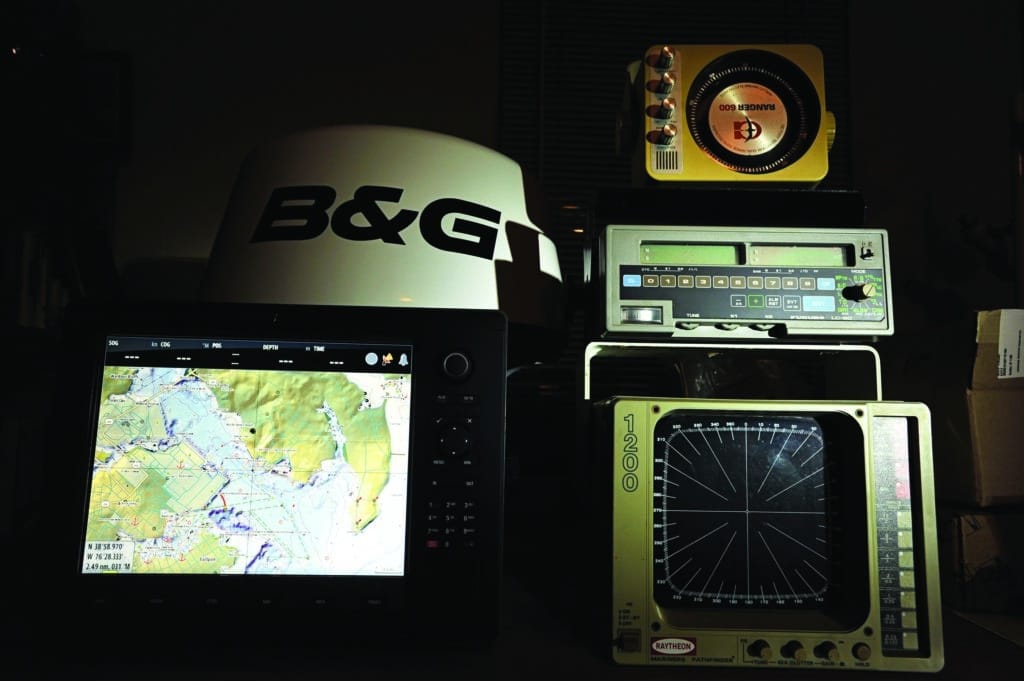

This mix of labels and vintages was all just fine in the stand-alone era, when a black box wasn’t lurking somewhere below, taking in data from an array of output devices and spewing it out to screens scattered from bow to stern. Oh, for the days when the chart plotter had yet to become today’s multifunction display! Some would even say that retaining this “stand-alone” mind set, where each unit has its own power cable, display and electronic autonomy, is the right answer when it comes to coping with a mix-and-match multibrand nav station. However, there are other options for boat electronics.

With the proper cables and devices, today it’s possible to interface an array of onboard instruments and enhance their ability to share a common data stream. These inputs can come from the masthead anemometer, the depth sounder transducer in the bottom of the bilge, or anything in between. This digital dialogue, at its most basic, relies on a stream of bytes running through special cables at nearly the speed of light. All are ducted to a controller area network (CAN bus) — a bit of automotive brilliance put to good use in the marine industry. Those with older, but not quite antique, boat electronic gear can sometimes use an instrument’s NMEA 0183 data feed to “talk” with more modern NMEA 2000-compliant devices, or even employ an analog-to-digital signal converter to breathe new life into older components. But the more esoteric the networking solution becomes, the bigger the bill and the more poignant the question: Is it really worth it?

To get a good answer, I spoke with boat electronics pro Bob Campbell of Annapolis, Maryland, who had sage advice when it comes to electronically interfacing a diverse gaggle of gadgets.

His first priority is helping the boat owner consider electronic gear as a navigation system rather than individual components. Before focusing on specific brands, the next step is to develop a realistic two-column list of gear under the headings “Must Have” and “Might Want.”

Once that’s completed, Campbell’s advice is to steer clear of brand hopping to minimize the need to lash one manufacturer’s equipment to another’s network. Carefully consider the value, cost savings and reliability that come from brand allegiance. Focus on the essentials and go with the gear line that hits the most points in the Must Have column.

Admittedly, Campbell does a lot of “transmutations,” often turning an analog signal from older equipment into digital compliance, but it can be a costly and complicated process. He often reminds owners that there’s a point where Kenny Rogers’ “fold ’em” theory is the best way to play your hand.

When the right tack is a clean sweep to a new system, Campbell says, the result is faster processor(s), higher resolution, more user-friendly MFD, plus better reliability and more flexibility. A good resource when it comes to planning an electronics makeover is the manufacturers themselves. Many have already included some backward compatibility in their new gear, and can answer questions about which of their black boxes will converse with previously installed units. Naturally, they’d prefer you buy a whole new system, and that may be the best solution in the long run. But you can take baby steps: If you are pleased with the mainstay of the gear in your nav station, a partial upgrade can be a smart move.

Bring your lingering questions to a local or regional boat show to chat with a factory-trained technician familiar with your gear. A very typical questions is “Can I network my older wind instruments with my new MFD?” If the units are from the same manufacturer the answer is probably yes, but if interfacing requires more complex custom analog-to-digital signal conversion, it’s likely time to consider a wind-instrument upgrade or live with the apparent wind direction and speed as stand-alone data.

DIY Advice from the Pros

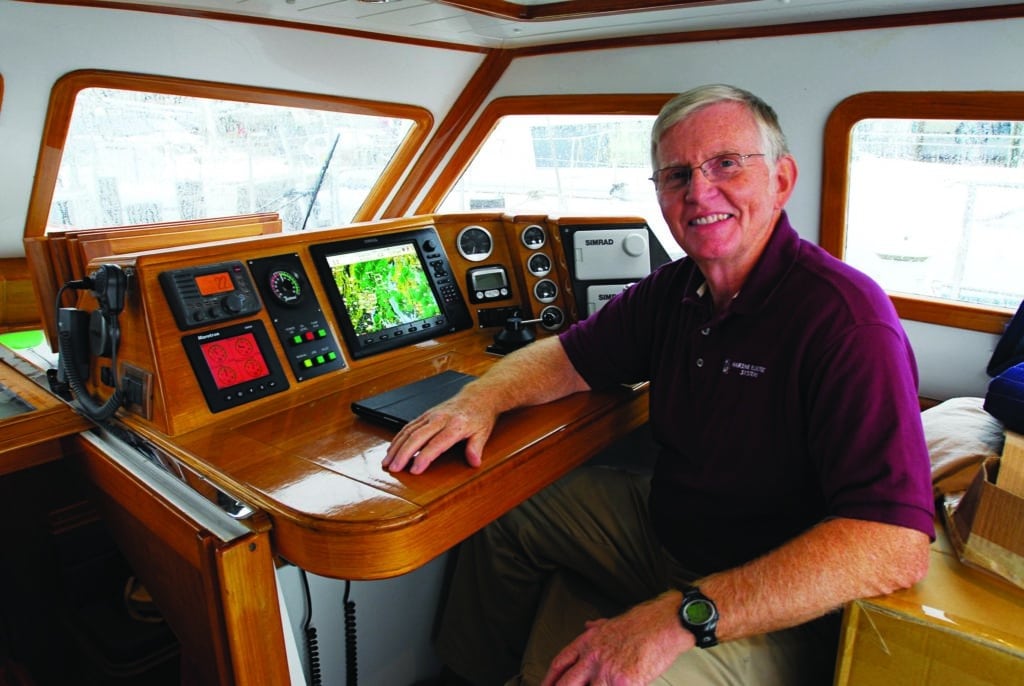

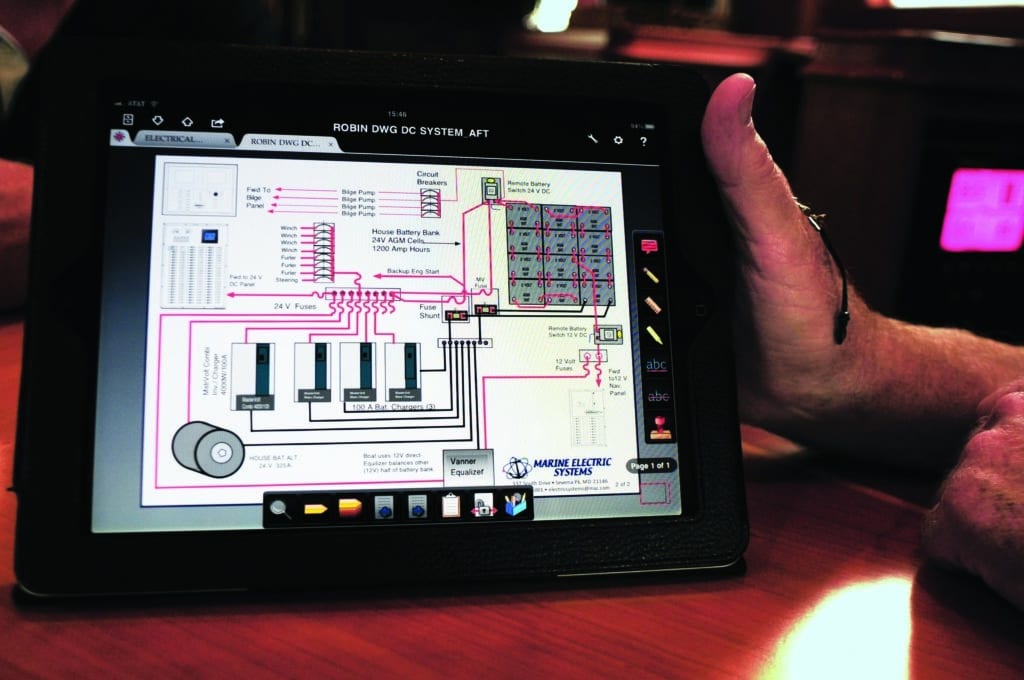

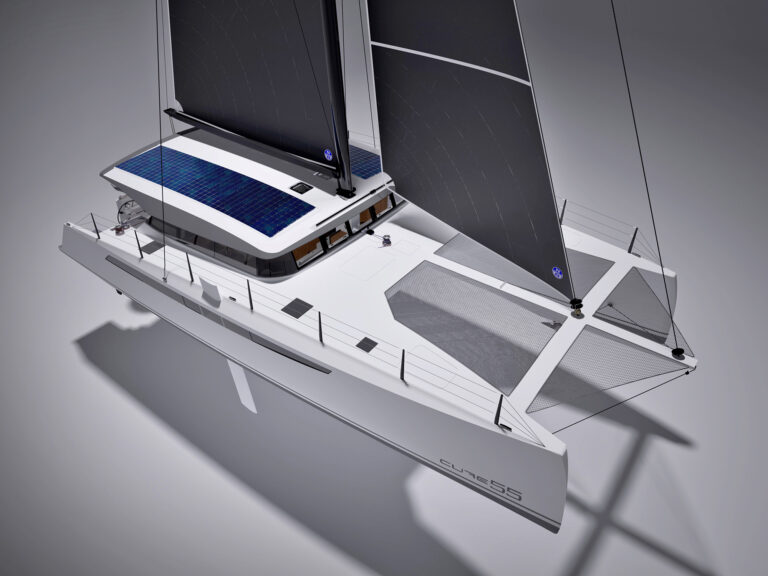

For those tackling their own electronics installations, there’s nothing more informative than watching a skilled team of pros go through a complete electronics refit. When I met with the crew of Annapolis-based Marine Electric Systems they were in the midst of a major makeover on a complicated 55-foot uber-networked cruising boat. The project was a lesson in how to set up a complicated network, and where the big challenges lie. Strict attention to detail was the underlying refrain. The crew crimped dozens of connections; securely sealed network cable plugs; and merged the antenna, digital compass and autopilot feedback leads. Little things like a loosely crimped connection could lead to moisture intrusion, corrosion and a changed impedance — a combination that’s not always easy to find and can cause lingering problems.

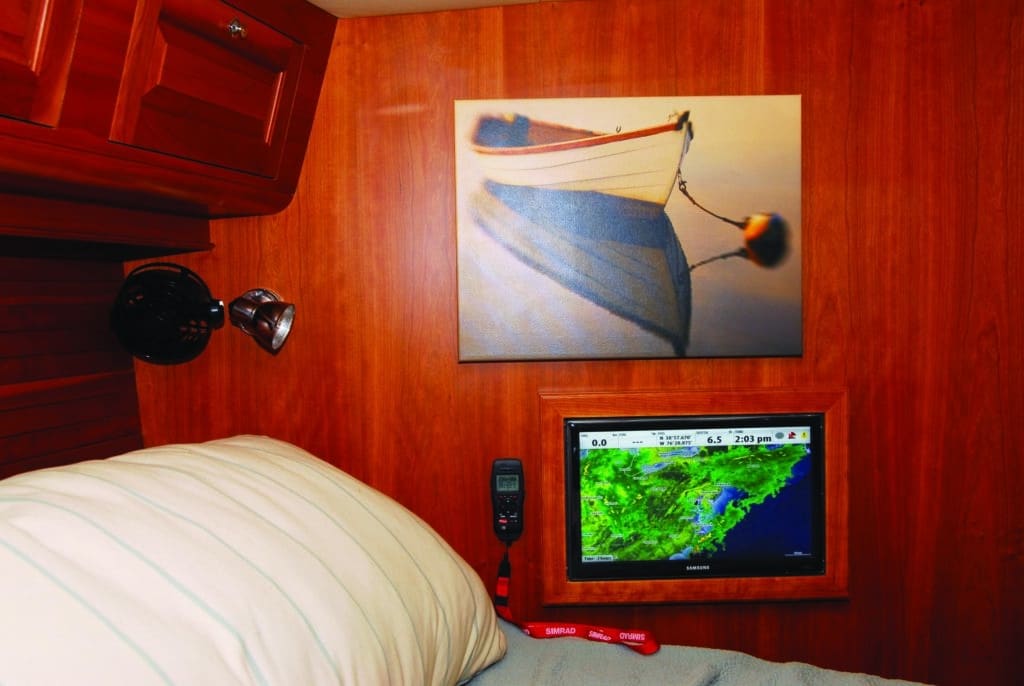

Campbell and crew stressed the importance of an owner’s developing a viable electronics game plan, one in which the operational goals merge with what’s technically achievable. In this case, the installation included an Ethernet, NMEA 0183/NMEA 2000 and proprietary cabled network with enough expansion capacity to cope with additional equipment. A sky’s-the-limit options list included dual GPS and GLONASS (the Russian equivalent of GPS) position inputs, and radar, AIS, weather and FLIR data streams can be overlaid on digital charts. There was also a desire to display this avalanche of information on large-format screens and on multiple displays. Fortunately, on this boat at least, the bad habit of breaking a 7-inch MFD screen into three sections to show cartography, a radar image and boat stats wasn’t considered. (In such situations, essential detail is hidden by the diminutive size of the screen.)

By the refit’s conclusion, it was clear that today’s top-end electronics installers have engineering and technical skills akin to what you’d find in the aviation industry. For the DIYer, there’s a lot to be learned.

As system complexity grows linearly, networking demands expand exponentially. For the self-reliant cruiser, consider limiting your needs to a fairly simple two-station system, and commit to single-brand allegiance. Installation becomes much easier and keeps the challenge of maintenance and operation within your grasp. If you have champagne tastes and a budget to match, find a skilled pro, work out a detailed quote and invest in a job well done.

The Screens Are Just the Start

When embarking on an electronics upgrade, remember that the retail price for the components is just the beginning. Each manufacturer has its own network architecture and proprietary waterproof cabling, control nodes, junction boxes, rate gyros, antennas, etc. The cost of options and the need for complex cabling increase with the number of peripherals to be networked. If planning a do-it-yourself project, look at the online installation manuals of the prospective gear. Most hardware comes with bracket mounts that eliminate the need for complex recessed joiner work. Even cockpit installations can be done using pre-manufactured pedestal-mount boxes, saving time and the need for special carpentry or fiberglass fabrications.

The really big-screen “glass helm” extravaganza seen on many motor yachts is a wonderful aid to navigation, but it’s overkill on the average cruising sailboat. The daily current consumption of such a system can be greater than the load your refrigeration places on the house battery bank. This means running the engine while you’re under sail in order to create power for the nav station. Part of the big-picture planning process is ensuring that the energy appetite of your networked electronics is in keeping with your boat’s battery bank. Engineering into the system an ability to turn individual equipment on and off — for example, to be able to run the depth sounder and chart plotter without activating unnecessary components in the network — is a big plus. After all, that’s exactly what you could do with the stand-alone architecture, an approach that still has a reasoned and vocal following.

Like many other sailors, I find myself overly attached to familiar equipment. Though I long ago switched to GPS, it took the U.S. Coast Guard’s curtailing Loran signal transmissions to get me to finally retire the receiver. Until recently, I’d held the same commitment to advocating for stand-alone electronic equipment. Aboard our sailboat, Wind Shadow, electronic simplicity had meant a GPS, sounder and conventional piloting/paper chart routine. But I finally made the transition, and wondered why I had waited so long. I like to think of this as a fully considered commitment to technology — not a borderline Luddite complex. Either way, I made a clean-sweep upgrade and did the work myself. The nav station on Wind Shadow now sports a 12-inch MFD chart plotter/radar combo that juggles a GPS signal, depth sounder input and a rate gyro signal to make the autopilot happy. I have leveraged one manufacturer’s components, cabling and installation wisdom. On the horizon is a smaller MFD for the cockpit.

Previously, I’d bootlegged a modern approach to navigation with Nobeltec software on my laptop and an iNavX app on my iPad (Luddite complex resolved!). But in case of bad weather, I wanted a fixed, waterproof, hands-free display installed in a known location. The reason I have the larger-screen MFD located below is that my wife, Lenore, and I sail double-handed and in tricky piloting situations we prefer the off-watch person to handle the radar and plotter down below while the person on watch tackles boat handling and keeps a lookout.

With this streamlined approach to networking, I found the manufacturer’s plug-and-play wiring to be quite straightforward. The radar uses an Ethernet link and all the other components use a mini-C or micro type of proprietary cabling. The biggest issues were the constraints imposed by joinery that made running wires through tight spaces and finding the right location for junction boxes a slight challenge. To minimize surprises during and after the installation, I set up the gear in my workshop and became familiar with the cabling and junction-box configurations ahead of time.

Furuno, Garmin, Navico (Simrad and B&G) and Raymarine have each committed to a sensible proprietary approach to networking onboard electronics. Each has its own unique features and user interface, so it’s up to you to investigate each and choose the overall system that best meets your needs. The navigational advantage such integrated packages offer is compelling, making it easier than ever to discern where you are and where you’re headed. What’s left is the responsibility of a crew to leverage all the value unleashed by such an electronic navigation network.

Ralph Naranjo is a frequent CW contributor.

This article first appeared in Cruising World March, 2014.