Murphy1

For a technology that’s been around in one form or another for more than 100 years, you might say that electric propulsion’s been a long time in coming to cruising boats. But that’s all changing now, and changing fast, as builders adapt what made sense in commercial, military, and day-boat applications for use in sailboats on a production scale.

Lagoon, the world’s most prolific catamaran builder, designed its new 420 Hybrid model around electric motors exclusively. The Moorings, the world’s biggest charter outfit, features an integrated diesel/electric package in a 43-foot catamaran built by Robertson and Caine. Still other builders of both powerboats and sailboats, monohulls and multihulls, are beginning to launch diesel/electric and hybrid models in numbers that qualify as a bona fide trend. Now, after its slow start, these alternative drive systems are evolving so quickly, in fact, that in some cases, they’re pulling ahead of the standards bodies that govern their use. (See “How Low Is Low?,” at bottom of page.)

So let’s look at what electric propulsion is and where it’s going.

Bring on the Brushless Motor

That story begins with a magnet-specifically, a neodymium magnet. Widely used in computer hard drives and stereo speakers, neodymium magnets have become more commercially viable in recent years, opening one of the doors for an emerging propulsion technology. The magnets are at the heart of today’s brushless direct-current motors, and these motors are at the heart of the diesel/electric revolution.

Opening the other door has been computer technology-specifically, the gee-whiz software it takes to distribute high-voltage DC current to the three poles of an electric motor, spinning the magnets around the motor’s axis and developing the torque it takes to push tens of tons of displacement at hull speed. This is part of a broader trend toward electronic networking throughout all of a boat’s systems. The backbone of these networks is a protocol called the Control Area Network, or CANbus, first developed for the automotive industry and subsequently adopted by the National Marine Manufacturers Association in its NMEA 2000 networking standard. Now, instead of relying on mechanical switches to distribute power and on fuses or circuit breakers to protect a boat’s electrical circuits, digital distribution panels perform these functions electronically-“smartly,” in the parlance of the computer age.

Right now, the state of the art in terms of the intersection between electronics and machines in a marine context is found in these new electric-propulsion motors. Electronic controllers have replaced the commutator in a conventional “brushed” electric motor. A commutator makes physical contact to deliver electrical power between the motor’s fixed stator and its spinning rotor-with undesirable byproducts ranging from sparking and radio-frequency interference to overall inefficiency and short maintenance cycles because of wear; however, in a brushless DC motor, there’s no physical contact between the moving parts, except at the bearings, which can be rated to last 40,000 hours or more.

From a mechanical perspective, two traits of electric motors are especially exciting for cruising sailors: the way they develop torque, and the ability they offer to decouple the propeller’s rpm from that of an internal-combustion engine. Consider that a diesel engine must maintain a minimum rpm or it will stall when it’s put in gear. This means that even at idle, when the transmission is shifted out of neutral, the prop begins spinning at a predetermined rate. Electric motors, by contrast, can generate torque as soon as electrons start flowing; this means they turn a prop at infinitely variable speeds-providing improved boathandling, most notably at low rpm.

In systems that rely on a genset to power the electric motors, decoupling the engine from the prop allows builders to size the genset’s engine most efficiently for the loads and install it in the boat for ideal weight placement and sound insulation. Taken together, these facts eliminate geared transmissions altogether-a further boon for efficiency.

Developing a Hybrid Technology

Two approaches to electric propulsion are evolving today: those that supply electrical power to the motor from a big battery bank (the “hybrid” approach), and those that rely on a running genset to power the motors (the “diesel/electric” approach).

In 1993, a former U.S. Navy engineer named David Tether gave a big boost to hybrid technology on recreational boats when he founded Solomon Technologies Inc. (See “Perpetuated Motion,” March 2005; see also “Solomon Technologies Revisited,” in Shoreline, June 2005.) His studies of efficiency in various power plants for the Navy led him to design a 144-volt motor supplied by a bank of a dozen 12-volt batteries wired in series. For sailors interested in hybrid propulsion today, those batteries are at the core of your choice. They offer the promise of “regeneration”-collecting electricity from the boat’s passage through the water when it’s under sail. We described earlier how electrical power spins the magnets in a brushless DC motor to turn the props to push a boat. Well, the same thing works the other way: a boat under sail spins a prop that turns the electric motor, which sends electric pulses back through the controller to refill the battery bank. But, of course, all those batteries come at the cost of space, weight, and dollars, and that regenerated energy comes at the cost of boat speed, thanks to the drag of the large propellers.

STI made news in early 2004 when it went public and began attracting such prominent sailboat builders as Groupe Beneteau (Lagoon), Hinckley, and others. But in early 2005, STI reorganized, Tether resigned, and STI actively pursued strategies apart from recreational boats.

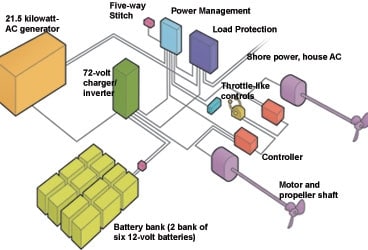

Lagoon subsequently consulted with Tether and designed its own hybrid propulsion system in-house, based around motors running at 72 volts and two banks of six batteries each. The Lagoon 420 Hybrid is the first cruising boat to feature electric motors as its standard propulsion package. One of three prototypes came to last season’s U.S. Sailboat Show, in Annapolis, Maryland, and to Strictly Sail Miami; according to Nick Harvey, director of Lagoon America, at press time the company had taken orders for 100.

Any new technology begins with an initial trial-and-error phase. When CW reviewers sailed the prototype in October, only one of the cat’s two motors worked, a problem Lagoon attributed to a software glitch in the controller. “We’ve worked very hard with our suppliers in the past six months to increase the reliability of the various components, and we have achieved our goals,” Harvey said in March. The same boat that CW sailed in Annapolis last fall was leaving Panama in April en route to New Zealand and, according to Harvey, all systems were “go.”

And Lagoon’s future plans? “We’re actively working on finding ways to better manage and use the energy stored in the batteries and also to maximize the efficiency of regeneration.”

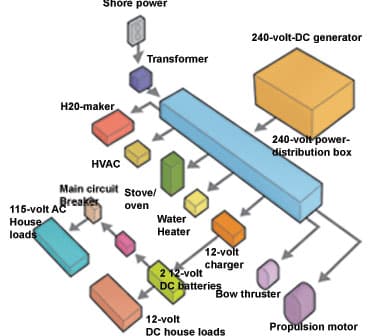

Joseph Comeau| |The Ossa Powerlite Diesel/Electric engine relies on a 240-volt-DC generator to provide all of the electric power needs of the Moorings 4300 Electric catamaran. DC current flows into a software-controlled power-distribution box that then routes current at the appropriate AC or DC voltage to Ossa Powerlite components, including motorsl heating, ventilating, and AC gear; cooking appliances; the watermaker; and power inverters.|

David Tether, for his part, recently founded a new company, Electric Marine Propulsion, based in Fort Myers, Florida. He still favors motors that run at 144 volts, tacitly alluding to the Ohm’s-law notion that amperage increases as voltage decreases for any given power. In practical terms, that means his higher-voltage motors would allow for the use of smaller wires, which would mean less weight, a critical concern on multihulls. Tether also says that the higher-voltage motors generate less heat.

One of EMP’s projects is to install hybrid propulsion in a line of 55-foot Dudley Dix-designed performance catamarans being built by former Gunboat builder Phil Harvey in Trinidad. One customer is Bill Choice, a longtime Hobie Cat racer who circumnavigated from 1989 to 2000 aboard a Wauquiez Centurion 47. “The advantages of a hybrid approach for sailboats are even greater than for automobiles, because sailboats have another source of power to tap: the wind,” Choice says. He reckons his hybrid system, which incorporates two gensets and two motors, will cost a third more than if he’d installed two traditional diesel engines and a genset. But for him, that initial investment is outweighed by the advantages, which include cost of ownership and fuel savings brought about by the efficiencies gained throughout the propulsion system; less noise, fumes, vibrations, and heat in the aft cabins; easier maintenance on the gensets; greater maneuverability with faster prop response and greater torque for motoring into wind and swells; regeneration capabilities, especially at sea; better weight distribution of equipment around the boat; and improved resale potential.

“The industry is going this way,” he said.

Battery (Banks) Not Required

For several years, STI’s hybrid approach was the only choice, practically speaking, for sailors and boatbuilders interested in electric propulsion. But that, too, is changing. At the Miami International Boat Show in February, The Moorings introduced a 43-foot cat featuring optional electric propulsion from Glacier Bay. Maine Cat, builder of the 41-footer that won CW’s Boat of the Year multihull category in 2005, will launch hull number 17 this spring with Glacier Bay’s diesel/electric package installed as an option. Also this spring, Maine Cat is introducing a new 40-foot powercat featuring electric motors exclusively.

OSSA Powerlite is the name of the Glacier Bay drive unit that all these builders are talking about; it’s a single, integrated system that encompasses not just propulsion but all of a modern cruising boat’s power generation and accessories. According to Wayne Goldman, head of OSSA Powerlite sales, Glacier Bay is now working with more than 10 production boatbuilders, and that number is growing.

“Glacier Bay is a good company with a lot of money and a new plant,” said Maine Cat builder Dick Vermeulen. “The people are on fire, and they’ve got a great warranty: If there’s any problem, they’ll take out that component and replace it.” While Vermeulen likes the theory behind today’s hybrid systems, he finds that Glacier Bay’s “engineering execution is far superior.”

The centerpiece of the OSSA Powerlite system is an efficient, variable-speed DC genset. That efficiency follows from three new technologies: one in the genset’s diesel plant, one in the generator component, and one in the interface between the two. The diesel plant, developed with Mercedes, features common-rail injection for improved fuel efficiency. It’s a technology that’s been used in trucks and high-end automobiles in the last decade; what’s new is its application to engines as small as those that drive a 25-kilowatt generator. The generator itself is a permanent-magnet brushless motor of the kind described earlier, with all the same advantages in efficiency and shorter maintenance schedules. And the third innovation is a CANbus interface between the power plant and the generator that matches engine speed with the real-time loads from the boat’s systems.

The result? “Our generators produce over twice the power for the same weight or space as our competition and emit less than a quarter of the particulates of comparable products,” said Glacier Bay president Kevin Alston.

Building on that genset platform, OSSA Powerlite offers a range of power-matched accessories, from propulsion to refrigeration, stoves, heat, air conditioning, water heaters, bow thrusters, windlasses, winches, furlers, battery chargers, and more. Depending on the loads, OSSA Powerlite gensets feed DC power at anywhere from 120 volts to 800 volts. Typical draw for the big items-air conditioning, watermakers, battery chargers-is between 120 volts and 240 volts DC.

Tony West is an enthusiastic Glacier Bay customer. The former chief technology executive for Sun Microsystems, West retired two years ago and brought The Moorings and Robertson and Caine together with Glacier Bay to build Electric Leopard, the 43-foot catamaran that was on display at the Miami show. He’d looked carefully at both hybrid and diesel/electric options before going with OSSA Powerlite.

“I knew when I bought my boat that it was going into charter,” West said. “The usage mode of such boats isn’t long-haul cruising but short-haul sailing. Since you’re not sailing for more than a couple of hours at a time, you don’t pick up enough regeneration from sailing to be worth lugging the batteries around.” For that kind of use, he wanted to avoid “the charge/discharge management of a large bank of series-connected batteries” and the risks he saw of extremely short battery-life cycles.

The best thing about OSSA Powerlite? “It’s a system,” said West. “The components are all connected and communicate with one another via a CANbus network, so you can look down into each device and get detailed status information about what’s going on.”

At press time, West hadn’t yet performed careful fuel-consumption tests, but he thinks the boat consumes about a gallon and a half (6 liters) per hour at full power, or at about 8 knots. A normal 4300 would burn 1 gallon per hour per engine at a cruising speed of 7-8 knots.

According to Josephine Williams at The Moorings, the OSSA Powerlite package adds $44,000 to the $400,000 standard boat.

What the Future May Hold

Apart from Glacier Bay, Lagoon, and Electric Marine Propulsion, several other companies are worth keeping an eye on in the near term. Foremost of these is Fischer Panda, best known for its variable-speed gensets. The company has been developing both a DC and an AC propulsion system under the Whisperprop brand. At present, it’s testing it in Europe but not marketing it in North America. Another is a small company called Re-E-Power, which offers skeg-shaped “pods” comprising electric motors and propellers designed to be easily installed by either a do-it-yourselfer or a professional yard. The pods look like an interesting small-boat alternative; a recent installation was on a Com-Pac sloop. At the other end of the yacht spectrum, the German company Siemens has been supplying electric propulsion to megayachts, but at present it isn’t marketing systems designed for smaller, owner-operator boats.

Still more exciting are likely new developments in the components that should improve all of these systems. For example, we’ve long known that lithium-ion batteries have a much higher power density than their lead-acid counterparts, but they’ve never been available in capacities large enough to meet the power needs of cruising boats. That time is now coming, and it’ll be a huge boon for hybrid systems whose biggest downside currently is the size and weight of the batteries. And there are promising new developments on the power-generation front. Every one of the leaders in electric propulsion today-Electric Marine Propulsion, Glacier Bay, Lagoon-has designed their systems in a modular way to accommodate the next new thing that’ll get us where we’re going more quietly and ever more cleanly than before.

Tim Murphy is a Cruising World editor at large.

How Low Is Low?

A word about high and low voltage and the standards that dictate how systems are installed aboard a sailboat. The American Boat & Yacht Council, International Standards Organization, and National Fire Protection Association define “low-voltage” DC as anything below 50 volts. Glacier Bay, by contrast, makes a point of calling its accessories “low voltage,” although they often draw 120 volts or more. When asked about this discrepancy, Kevin Alston said, “International certifications and legal definitions for voltage descriptions are based on the following: “extra-low-voltage” is below 120 volts; “low-voltage” is between 120 and 750 volts.”

The point here is that we’re heading into new territory, and not all standards bodies have reached a consensus on these definitions or their safety implications. ABYC representatives say they plan to weigh in on this issue soon.

For Further Information

Dudley Dix Yacht Design: www.dixdesign.com.

Electric Marine Propulsion: www.electricmarinepropulsion.org.

Electrosail: www.electrosail.com.

Fischer Panda: www.fischerpanda.com.

Glacier Bay (OSSA Powerlite): www.ossapowerlite.com.

Lagoon America: www.lagoonamerica.com.

Maine Cat: www.mecat.com.

National Marine Manufacturers Association: www.nmea.org.

Re-E-Power: www.re-e-power.com.

Solomon Technologies Inc.: www.solomontechnologies.com.

The Moorings: www.moorings.com