John Lombardi 368

Donald McKay built clipper ships; Henry Nivens built yachts. Both imbued their vessels with their character and their artisanry. The same devotion to craft is evident today in their successors, of whom John Lombardi is, if not typical, certainly an exemplar.

Donald McKay built clipper ships; Henry Nivens built yachts. Both imbued their vessels with their character and their artisanry. The same devotion to craft is evident today in their successors, of whom John Lombardi is, if not typical, certainly an exemplar.

Lombardi’s three acres off Virginia’s Mobjack Bay is a sort of Elysian Fields for multihull fans. On a visit in the spring of last year, two Farrier folding trimarans, an F-39 and an F-22, were taking form in the sheds, a Chris White Atlantic 54 was parked outside, being finished by its owner, and the F-32 that wowed the crowd at the 2008 U.S. Sailboat Show in Annapolis, Maryland, was tied to the dock. A Dick Newick trimaran lay at the high-water mark a few yards away from Pacific Bee, the proa built by Russell Brown and a close sister to Jzerro, which Brown built and in 2000 sailed across the Pacific. (See Steve Callahan’s “A Starship to Oceania,” March 2001.) Russell’s brother, Steve, has a project under way in the yard, and their father, Jim Brown, the guru in this world of water skimmers, lives just down the road.

In the back shed, several laminated parts shaped like pieces cut out of an enormous onion lay across a couple of sawhorses. On the adjacent bench was an orderly pile of foam offcuts that I assumed were scrap until Lombardi picked one up-it was wedge shaped and about half the size of my little finger-and said, “Every one of these is part of an assembly for the Farrier next door.”

It takes a special individual to keep straight these intricate details and render them with craft and artistry into the birdlike structure that is a folding trimaran. And it’s easy to admire the end result, which rests on, rather than in, the water. The appeal of these craft lies in their delicacy of line and their urgency of movement. They aren’t built to bear the trappings of the 21st century but, like their Polynesian forbears, as Callahan wrote in his story about Jzerro, “to happily tiptoe down the path of least resistance” across a sea of dreams.

Donald McKay wouldn’t recognize these vessels, but he’d no doubt appreciate the dedication with which Lombardi builds them.

John Lombardi’s path to boatbuilding was written in the stars, not on his career plan. He has a degree in Fine Arts from East Carolina University-he still finds time to paint watercolors-and he’s designed kitchenware for upscale retailers and made pottery on a production line. Boats entered Lombardi’s consciousness at college, where he minored in woodworking and found his skills in demand at a boatyard in Washington, North Carolina, near the university’s Greenville campus, fashioning the intricate parts of Chris-Crafts and other old woodies being repaired or restored.

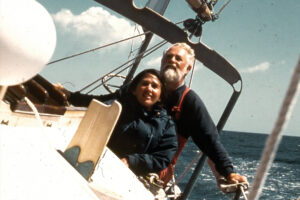

While working on boats, he had a vision of sailing over the horizon, but instead of building that boat, he’s built the craft that have sent his clients in pursuit of their dreams. Among those boats are nine built to Chris White’s Atlantic 42 design. With the first of them, Lombardi won the Best Multihull award in the 1998 Cruising World Boat of the Year contest.

Thus far, every time he’s completed a boat, Lombardi has said, “I think I have another boat in me.” Finding the client for it has been a challenge these past couple of years, but by contracting for other composite specialists while doing repair work in his own shop and a little commercial fishing, he’s kept the doors open.

On a sunny Sunday this past spring, those doors opened to let out one completed Farrier F-39 and admit another for substantial updating. For a couple of hours, trimarans took flight as a crane hopscotched them around the yard, choreography by John Lombardi.

Jeremy McGeary is a CW contributing editor