I roll off the cockpit settee, pop my head over the dodger and look into the night. Twenty degrees off our starboard bow, I do see it: three white lights in a vertical line, then a red light below and to the left of the others.

“I’ve been watching him for a while,” Hank says. “His bearing hasn’t changed.”

My first reaction is to call for an exaggerated turn to port. As I try to shake off sleep, an exam question flickers from some dim recess.

You are approaching another vessel at night. You can see both red and green sidelights and, above the level of the sidelights, three white lights in a vertical line. The vessel may be

a. not under command

b. towing a tow more than 200 meters astern

c. trawling

d. underway and dredging

My heart races before I call for the course change; another question runs through my mind.

You are aboard the give-way vessel in a crossing situation. Which of the following should you NOT do in obeying the Navigation Rules?

a. cross ahead of the stand-on vessel

b. make a large course change to starboard

c. slow your vessel

d. back your vessel

Adrenaline wallops me. “Turn 90 degrees to starboard,” I say.

For the next minute or so, the tug moves safely across our port side, and soon we both see the faint red sidelight of its barge some hundreds of yards behind. I think of the hawser connecting them, lethal and invisible, then sit chatting with Hank for a few minutes before lying back down for another 20-minute nap. (For the record, the correct answers are B and A.)

Hands-On Sailors

I’ve joined Shawn Brown and Hank Schmidt as their instructor for a pair of courses — Coastal Navigation and Coastal Passage Making — two intermediate steps in a tiered curriculum from novice to expert that’s created and administered by the United States Sailing Association, or US Sailing. Shawn is an airplane pilot who’s recently left a tech startup and is now looking to buy a 50-something-foot ketch to live and cruise aboard. Hank (no relation to the Hank Schmitt who organizes cruising rallies under the Offshore Passage Opportunities name) is a New York City emergency-room physician who hopes to start crewing on ocean-sailing trips from the U.S. East Coast to the Caribbean. Both would like to charter sailboats in different places around the world. If they can successfully perform the hands-on tasks laid out in each course and pass the written exams, they’ll receive US Sailing certificates that demonstrate to charter companies and skippers that they’ve attained a rigorous level of proficiency in these disciplines.

For this trip, we’re sailing Matilda, a newish Hanse 505 managed by New England Sailing Center in Newport, Rhode Island. The Coastal Passage Making curriculum includes night passages, so we plot a track that will take us from Narragansett Bay out to Shelter Island at the eastern end of Long Island, then across Block Island Sound to Martha’s Vineyard, before returning to Newport — a triangle of some 200 miles over five days, including two overnighters.

After stowing provisions and getting familiar with the boat’s systems, we work through this question together:

The Hanse 505 is fitted with a Volvo D2 diesel engine and 75 gallons of fuel. If she cruises at 6.5 knots and burns 1.75 gallons per hour at 2,200 rpm, what is *Matilda‘s safe cruising range under power?*

a. 75 miles

b. 175 miles

c. 275 miles

d. 375 miles

It takes two steps to answer the question. We know that the engine burns 1.75 gallons per hour and that Matilda will travel a distance of 6.5 miles in one hour. Our first step is to figure out how far we’ll travel on a gallon of fuel. Dividing 6.5 miles by 1.75 gallons gives the answer: 3.71 miles per gallon.

Next, we need to know how far our tank of fuel will carry us. Multiplying 75 gallons by 3.71 miles per gallon gives a result of 278 miles. Answer C, 275 miles, is mathematically possible but not a safe cruising range. Applying a safety factor of 25 percent leaves us with a range of 208 miles. The answer B, 175 miles, leaves us a safety factor closer to a third of a tank. B is the best answer to this question. In practical terms, this means that even if the wind shuts off all week, we could still complete our itinerary without refueling.

We spend our first afternoon sailing in Narragansett Bay, calculating time-speed-distance problems and plotting course-to-steer vectors through the tidal current as we reach over the top of Conanicut Island, then tack down the West Passage to Dutch Harbor. Shawn and Hank study the chart and select a spot near the mouth of Great Creek that shows 14 feet of depth at mean low water and is marked with an “M” for its mud bottom. Calculating for 7-to-1 scope and taking into account the tidal range and our 5 feet of freeboard, they set the hook, then put out 160 feet of rode. We grill chicken, share a few laughs and turn in early.

Our trip’s first night passage begins at 0200.

From Lubber to Salt, Step by Step

US Sailing, which has existed in one form or another for more than 120 years, describes itself as “the national governing body for the sport of sailing.” In the 1980s, it got into the business of teaching sailing, with an initial focus on kids and small boats. In the 1990s, it began developing courses for adult sailors in bigger boats — “keelboats,” as opposed to dinghies, and cruising in addition to racing. Similar instructional programs are available that lead to American Sailing Association certification (see “ASA Courses and Certifications,” at the end of the article).

Two years ago, US Sailing reorganized itself to simplify its several missions. Now there’s a dedicated Youth department, which focuses on teaching kids to sail small boats through local sailing schools, yacht clubs and community sailing centers. Its Youth network includes some 1,500 instructors. Other US Sailing departments support sailboat racing up to the Olympic level, providing rules, coaching, measurements and other tools to create a level competitive playing field.

The courses Shawn and Hank are taking fall under US Sailing’s Adult department. Since January 2017, that division has been led by Betsy Alison, a champion in several senses of the word. Five-time winner of the Women’s Keelboat Championships, five-time Rolex Yachtswoman of the Year and 2011 National Sailing Hall of Fame inductee, her competitive record speaks for itself. But in a broader sense, Betsy has long been a champion of providing people access to the water, especially folks with clear barriers. In 2015, she won the ISAF World Sailing President’s Development Award for her work as head coach of the US Paralympic Sailing Program.

In her new role, Betsy’s mission has broadened. “We just want to get butts in boats,” she told me last winter. “We want people to try sailing and have a hands-on experiential learning opportunity that hopefully sparks their interest and makes them want to continue.”

For Betsy and her department, that mission starts with a program called First Sail. First Sail sessions typically run two hours and cost between $35 and $100 per person; after that, many clubs or schools offer discounts on future lessons. “We have First Sail locations that are not US Sailing keelboat schools or yacht clubs,” Betsy said. ”And we don’t mind whether someone is using ASA instructors or volunteer instructors or whatnot. It’s the first entry point in my department, and it’s for people who have never tried sailing before.”

The next step for folks who want to learn more is US Sailing’s Adult Keelboat program — and this is the track Shawn and Hank are following. The US Sailing website includes a list of accredited schools that offer certification. With about 75 schools on the list, that network is smaller than what you’ll find with US Sailing’s Youth program (1,500 instructors) or the American Sailing Association (roughly 300 schools and clubs).

The Adult Cruising Track lays out a progressive set of standardized stepping stones to lead novices toward sailing expertise:

- Basic Keelboat

- Basic Cruising

- Bareboat Cruising

- Cruising Catamaran Endorsement

- Coastal Navigation

- Coastal Passage Making

- Celestial Navigation

- Offshore Passage Making

In addition to these, US Sailing offers other targeted programs, including Safety at Sea courses and a host of online instruction. “If you look at the millennial generation,” Betsy said, “they don’t want to own things. They want to go to a community sailing program or to a shared-boat club and lease or charter a boat and enjoy it without having to make the big financial investment in it. So this year we’ve started expanding our small keelboat program.” For such people, certifications are their ticket to renting boats. So, US Sailing expanded its program last year to include Performance Keelboat. “It’s an opportunity to teach people to sail their boats better and faster without being related to racing.” It’s also unrelated to the more systems-heavy cruising track.

Another new course comes under the heading of US Powerboating. “What sets us apart from some of the other powerboat-instruction providers is that our programs are all focused around hands-on, experiential learning,” Betsy said. “So you learn how to pivot-turn; you learn how to dock and undock, and all the little nuances that you don’t get if you sit online for your boater’s education card.”

Bringing It All Home

The full reality of that hands-on, experiential instruction hits us at 0130, when wake-up alarms start ringing through Matilda‘s cabin. After that initial jolt, only the clatter of the anchor chain breaks the midnight silence as we hoist the main and sail off our anchor engineless. A gentle southerly and the ebbing current take us quietly out past the Dutch Harbor mooring field and back toward West Passage.

“See that red light that’s flashing twice then once every six seconds?” I say to Shawn. “Keep that just off our starboard bow.” This is the preferred-channel buoy “DI” at the south end of Dutch Island — red on top, green on the bottom, with a composite group-flash light pattern at night. We talk about how boats traveling north up the West Passage treat this navigation aid as a red mark if they intend to continue up the main channel but as a green mark if they’re going up the secondary channel into Dutch Harbor. When Shawn and Hank take their exam at the end of the week, they’ll remember this moment; at least five questions deal with aids to navigation, and more than one of those asks about preferred-channel buoys.

With sunrise off Point Judith comes the New England fog — the “smoky sou’wester,” as advection fog is known in these parts, recognizing the strange pairing of zero visibility with a ripping breeze. What should we do?

Shawn combs through the Navigation Rules to find out. Subpart D covers “Sound and Light Signals.” Rule 35 treats “Sound Signals in Restricted Visibility.”

That’s us.

“In or near an area of restricted visibility, whether by day or night,” he reads, “a power-driven vessel making way through the water shall sound at intervals of not more than two minutes, one prolonged blast.” Elsewhere we read that a prolonged blast sounds for four to six seconds.

Sure enough, we can hear one of those off our port beam — and it’s getting louder.

But that signal is for power-driven vessels, and we’re sailing with our engine off. What about us?

“A vessel not under command; a vessel restricted in her ability to maneuver, whether underway or at anchor; a sailing vessel; a vessel engaged in fishing, whether underway or at anchor; and a vessel engaged in towing or pushing another vessel shall … sound at intervals of not more than two minutes, three blasts in succession, namely, one prolonged followed by two short blasts.”

And so for the next three-quarters of an hour till the fog clears, we take turns blowing the air horn — one prolonged, two short blasts, every two minutes. The sound of the other boat moves aft, but we never catch sight of it.

Through the morning and the early afternoon, we devise a watch schedule to make up for last night’s short nap, and we set up a detailed log of our progress. All day we motor sail a little south of west toward Gardiners Point, keeping a close eye on the weather. The NOAA forecast calls for a powerful front arriving later and bringing gale-force winds through the night. We call up National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s graphic marine weather charts and compare the surface analysis with the 12-, 24- and 48-hour forecasts. We talk about the isobars, those lines of equal barometric pressure on the map, and how tighter isobars indicate greater wind velocities. We talk about the changing sky, and what the progress from cirrus to stratus to cumulus foretells. Later that night, safely anchored in Shelter Island’s Coecles Harbor, the shrieks through the rigging and the boat’s snappy pitch send home the message that what we’re learning here isn’t just theoretical.

The gale doesn’t quite blow itself out till early afternoon, so we use the next day for coursework at anchor: tide problems using the rule of twelfths, set-and-drift plots, safety procedures in cases of fire or crew overboard. We use the time to plot a current-corrected course back across Block Island Sound to Martha’s Vineyard. After a swim and a late lunch, we up anchor and set off in time to round Gardiners Point by sunset and begin our second overnight passage.

By the time we return to Newport after five days out, the exam questions for the Coastal Passage Making certification seem a little less daunting — and a little more real.

The greater the pressure difference between a high- and low-pressure center, the:

a. cooler the temperature will be

b. drier the air mass will be

c. warmer the temperature will be

d. greater the force of the wind will be

Fog formed by moisture-laden air moving across a cold portion of Earth’s surface and condensing is called:

a. sea fog

b. radiation fog

c. advection fog

d. frontal fog

A lighted preferred-channel buoy will show a:

a. Morse (A) white light

b. composite group flashing light

c. yellow light

d. fixed red light

To pass the course and gain their certification, Shawn and Hank need to answer at least 80 percent of these questions correctly (the answers to the questions above are D, C and B, respectively). That’s 64 out of 80. But after this week, all that theory from the textbook has been fleshed out with a boatload of indelible memories. All that said, this story has a happy ending: They passed.

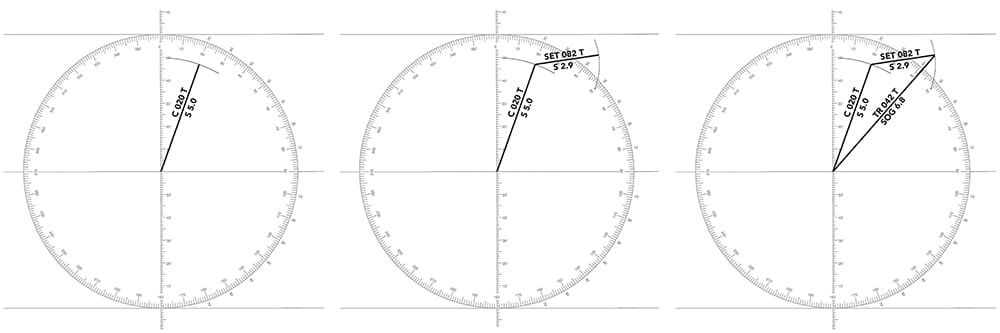

Plotting the Effect of Current

Step 1: We’ll use a universal plotting sheet to work out our current vectors. The plotting sheet is marked with units for distance and angle. We’ll use it to draw vectors, lines that represent both angle and distance. To solve problems for tidal current, the trick is to create a plot based on one hour of travel. That way our speed (knots) equals our distance (miles), and the length of each vector directly represents our speed. In this problem, we’re steering a course of 020 true and making 5 knots through the water. Using dividers with a pencil tip on one end, measure off 5 miles on the distance scale and make an arc near our course. Next, using the compass rose, line up parallel rules from the plotting sheet’s center mark through the 020 mark on the compass rose. Draw a line from the center to our pencil arc; this vector represents our course and boat speed. Above the line, label it “C 020 T.” The “C” reminds us that this is our course, uncorrected for current; the “T” reminds us that this is a true course, corrected for compass error. Below the line, label it “S 5.0”; the “S” reminds us that this is our boat speed (through the water, not over the ground).

Step 2: Now we’ll draw a second vector representing the current’s set (direction) and drift (speed). Using NOAA’s Tides & Currents tables, we’ve determined that the current is setting us at 082 true at a speed of 2.9 knots, so we can start by marking off a distance of 2.9 miles with the dividers. From the head of our course/speed vector, scribe an arc near 082. Set the parallel rules at the center of the plotting sheet and at 082 on the compass rose, then walk them to the head of the course/speed vector. Draw a line that intersects our second arc. Label these “SET 082 T” and “S 2.9.”

Step 3: Using parallel rules, draw the vector from the center of the plotting sheet to the head of the set/drift vector. Read the angle off the compass rose, then measure the distance with the dividers. This vector shows that our actual track is 042 true and our speed over the ground is 6.8 knots. Label this vector “TR 042 T” and “SOG 6.8.” We’ve solved for current. A plot on the chart based on this exercise would be called an “estimated position” — more accurate than a simple dead-reckoned position but still not as accurate as a positive fix.

ASA Courses and Certifications

Founded in 1983, the American Sailing Association has developed programs for sailing instruction that include textbooks and online courses, as well as classroom and on-the-water instruction. The ASA counts among its membership some 300 sailing schools and yacht clubs, as well as charter companies and professional sailing instructors. Its entry-level textbook, Sailing Made Easy, gets my vote for the best learn-to-sail book for novices. The ASA has developed standards for a series of progressive sailing certifications, including:

- ASA 101: Basic Keelboat Sailing

- ASA 103: Basic Coastal Cruising

- ASA 104: Bareboat Cruising

- ASA 105: Coastal Navigation

- ASA 106: Advanced Coastal Cruising

- ASA 107: Celestial Navigation

- ASA 108: Offshore Passage Making

- ASA 110: Basic Small Boat Sailing

- ASA 114: Cruising Catamaran

In addition to these broad standards, the ASA has also developed endorsements for more specialized skills:

- ASA 117: Basic Celestial Endorsement

- ASA 118: Docking Endorsement

- ASA 119: Marine Weather Endorsement

- ASA 120: Radar Endorsement

Be sure to check out ASA’s online courses too.

CW editor at large Tim Murphy holds a 100-ton Master’s license and has taught sailing for many years. He’s preparing a 1988 Passport 40, Billy Pilgrim, for long-distance voyaging.