Life throws its rough moments at you. I am in the midst of one right now as I help Larry, my husband and companion of more than 50 years, through the late stages of Parkinson’s disease. But as I stand on the end of the jetty, watching Noel and Litara Barrott sail Sina through the entrance to North Cove, near our New Zealand home on the island of Kawau, my thoughts are drawn back to a comment Larry made the second time we met this intrepid voyaging couple.

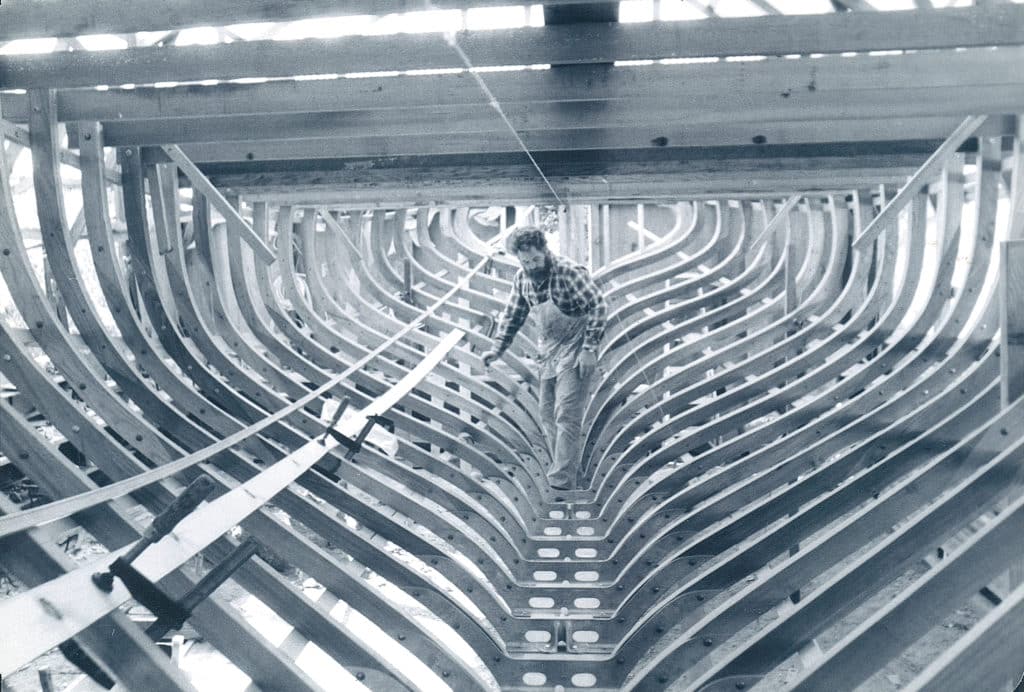

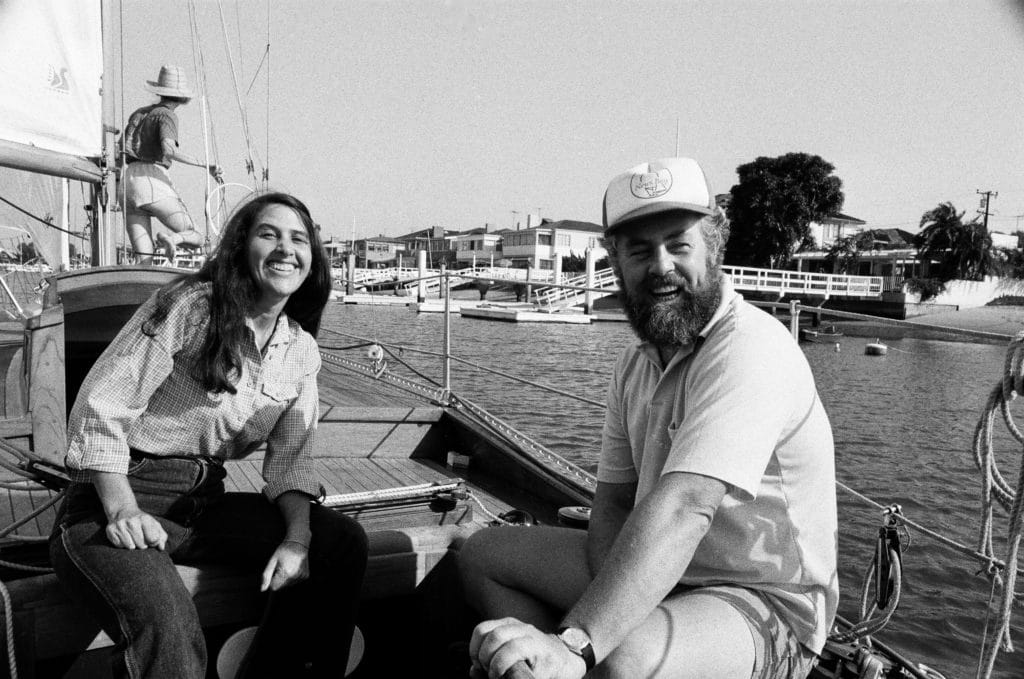

The first time was in the southern reaches of Canal Beagle. Stormy weather had forced us to seek shelter at the Chilean outpost of Puerto Williams and wait for a break before we headed back out into the South Atlantic for a second attempt at doubling Cape Horn aboard Taleisin. Noel and Litara were headed home toward New Zealand via the canals of southern Chile in their handsome self-built 53-foot yawl after a voyage to Iceland. Because Larry and Noel both love building wooden boats almost as much as they love sailing, the bond was immediate.

The second time we shared an anchorage was a month later, at Puerto Montt, after we’d successfully sailed back out into the Atlantic, then headed south of Cape Horn before beating north past the wind-blasted, rock-strewn lee shore of Chilean Patagonia. Noel and Litara, with their daughter Sina on board, had taken a far different route, exploring the glaciers and fjords of Canal Beagle before escaping into the open waters of the Pacific Ocean through Canal Trinidad. The first hours of that reunion were spent rehashing the four days of hurricane-force winds each of us had encountered just after sailing clear of the Furious 50s. Now, as I watch Noel and Litara round up into the 35-knot wind that roars across the cove, I remember Larry summing up our mutual heavy-weather stories by saying, “Only good thing about storms: They teach you patience.”

It is an important lesson to recall at this moment. And as I wait for Noel and Litara to secure their boat, launch the dinghy and row ashore, other lessons cruising taught me begin to leap into my mind, lessons that have stood me in good stead both at sea and ashore.

Everything Passes

Strangely, we actually found the storms we encountered at sea easier to endure than some of the storms that kept us harbor-bound in foreign ports. But in each case, as I look back, I realize the time did slide by. In hindsight, these trying times often created the best sense of shared purpose. I have memories of the encouragement we gave each other during stormy times at sea, reminding each other we’d worked hard to prepare ourselves and our boat to face these conditions and now had a chance to test our endurance and patience. But most of all, when the winds abated and we sailed into calmer waters, I remember the feeling of confidence gained and the sense of accomplishment.

Calms, too, pass. That is a lesson that slowly grows in importance the longer you cruise. To some sailors, calms represent frustration. But to others who have learned to put aside schedules, calms can be a time of quiet introspection. To Larry and me, sailing engine-free as we did, calms at sea were often our favorite times. Time to forget about sail trimming, to catch up with simple onboard chores so when we reached shore we had little left on our work list. Though we were rarely truly becalmed — when we couldn’t keep the boat moving even with our largest nylon sails — for more than a few hours at a time, we once had several days of complete calm as we crossed the Arabian Sea. The passage had so little wind, the 2,200-mile voyage took almost 36 days. So how does this translate to a useful lesson once you spend more time ashore than cruising? Once again, the lesson I learned is this: All calms eventually pass. Now, when I find myself looking at my calendar and thinking, Not much interesting planned for the next while, instead of rushing about looking for something to add, I remind myself to sit back, relax and drift with the moment.

Sometimes, Do Absolutely Nothing

One summer when we were cruising through the islands of Maine, I was invited to crew on a race boat with several very high-powered businessmen. As often happens in those waters, we were surrounded by heavy fog for four out of the five days. One day we’d been sitting on the rail for several hours, keeping as quiet as possible to ensure we would hear any approaching boat. We had nothing at all to look at but a sheet of gray dripping fog. The crewmember next to me broke the silence. “If someone caught me sitting and staring at a blank wall for two or three hours at a time they’d say I’d gone crazy,” he stated. “But if they saw me right now they’d just say, ‘He’s out sailing.’”

Back when we were cruising full time, I had a lot of time to myself during night watches, or times when Larry was taking a daytime nap. I didn’t always particularly feel like reading a book, but I didn’t feel the need to fill these hours with activity. It felt normal at the time because we were sailing. This too is a useful lesson cruising taught me. It is OK to sometimes do absolutely nothing, to let your mind rest or wander lazily among dozens of thoughts that would otherwise be drowned out in the noise of everyday life. Some truly refreshing and original ideas have occurred to me because I brought this practice to shore.

Be Spontaneous

We’d risen early one morning and worked our way free of the reef surrounding Huahine, French Polynesia. We were bound for the island of Raiatea. This was the second time we’d set off to make this 26-mile passage. The first time, we’d been becalmed exactly halfway across. Then the normal easterly trade winds reversed and came in strongly from the west. With dark falling, we decided it would be prudent to turn around and run back to Huahine. We would wait for a favorable wind and full daylight to pick our way through the reefs and coral heads surrounding the anchorage we wanted to reach in Raiatea.

Two days later, on our second attempt, we had wonderful sailing, with no sign of faltering trade winds. We’d been under way for just two hours when we noticed familiar-looking sails approaching from the west. Soon, two friends we’d first met a year previously in Mexico were alongside. “We’ve been working our tails off, fixing boats for the charter fleet in Raiatea,” Mike called as we hove-to a few dozen yards from each other. “We’re headed for Huahine to rent some motor scooters, catch up with some friends at the south of the island, do some diving and have a few days’ fun,” Mike continued. “Why don’t you turn around, come and play with us?” I didn’t have time to protest before Larry yelled, “Sure thing.” A week later, as we reached easily (and this time successfully) toward Raiatea, we had a fine time talking about the people Mike had introduced us to: Polynesians who welcomed us into their home, shared their meals, took us out fishing on the reef and gave us an insight into their culture.

When we first set off cruising and first came across opportunities like this, I remember remarking to Larry that it was easy to change plans because we didn’t really have any — just the desire to set sail and explore for four or five months. But plans did form, and sometimes I had to remember how important that spontaneity, that willingness to change plans, could be. It was definitely a lesson we brought to our onshore life.

Don’t Be Too Determined

In a way, this lesson goes hand in hand with the previous one. We’d had a fast, wet, windy and squall-prone run across the Indian Ocean, bound for the intriguing, isolated and deserted atolls of the Chagos Archipelago. It was a destination that had been on our wish list for years. When we were about 400 miles from the unmarked, unlit atolls, the weather became even more unstable: squalls with torrential rain overtaking us sometimes twice in an hour; 15- to 20-foot following seas; and gray and cloudy skies with low visibility between the squalls. “I’m just not willing to risk running down on a maze of underwater atolls in these conditions,” Larry said that evening. “We wouldn’t know we were in danger until we were already on top of a reef. Let’s slow the boat down and hope this weather system passes over us.” We reefed down to just a storm trysail. Our speed dropped from 7.4 knots to about 4.5 knots. Two days later, we were within 125 miles of the first underwater reef we’d have to negotiate to reach a safe anchorage. The weather had not improved. “OK, let’s heave to and wait for things to change,” I suggested. For two days we lay hove-to. Life was not uncomfortable; I didn’t resent the wait. But on the third morning, with squalls coming through just as often and the barometer unchanged, I agreed when Larry stated, “I don’t think Chagos is in the cards for us this time. Let’s go for a Plan B solution. Let’s reach south toward Rodrigues Island.” A day later, we sailed out of the near-gale-force winds, squalls and grayness into bright sunshine. Four days later, we were secured alongside a clean, palm-frond-covered stone quay right in the center of the capital of Rodrigues Island, enmeshed in one of the more memorable experiences of our cruising lives.

As an affirming footnote, the Rodrigues weather station, which tracks Indian Ocean weather systems, recorded almost three more weeks of heavy cloud cover, squalls and near-gale-force winds over Chagos. Several months later, in southern Africa, we met two sailors who had been bound from Malaysia toward Chagos just a week after us. They had radar and GPS on board, and carried on in spite of the weather, only to end up hitting the exact reef that had worried us most. They were fortunate to get their boat free after three weeks of very hard work. Repairing the damage once they reached South Africa cost them a year’s cruising funds.

Yes, this is a lesson we have carried into nonsailing situations, realizing when to step back and rethink a project, plan or scheme, to take a different tack. Sometimes we even have to admit that something just isn’t going to work and it’s time to let go and head in a new direction.

Take Time to Cultivate Friendships

This is the most important lesson of all. Everyone comments about the amazing friendships that develop when you are cruising. I’ve heard explanations such as, “I had something in common with everyone I met.” Or, “Everyone was so willing to be helpful with information and ideas.” But I think the real reason we found it so easy to make quick and lasting connections with people when we headed out cruising was that we actually took the time to do so, and once we came to know someone, we went out of our way to spend time with them. I can recall literally hundreds of afternoons when we lounged in our cockpit or lazed on the foreshore with someone we’d just met — other sailors, fishermen, the local couple we chatted with ashore and then invited on board for their very first visit to a yacht. Once we settled in the cockpit, the only distractions were the birds flying overhead, the fish breaking the surface, maybe a boatman rowing past. This uninterrupted time let us leisurely find the common ground that tends to make all people appear helpful, friendly and interesting. These afternoons sometimes stretched right through dinner and late into the evening. We almost always felt the time had been well-spent. And once we made these new friends, we went out of our way to spend lots of time with them over the next days, knowing we might not ever get to spend time with them again. This is harder to do ashore, but using this cruising lesson — making extra time for new people I meet, turning off my telephone, loosening up any schedules and being open to each person who comes into my life — has definitely paid dividends.

Yes, cruising taught me many lessons, and when I use them, life does seem to flow more smoothly. The hard part is recalling them through the hustle of shoreside life. But today, standing on the jetty, I remember to use the lessons. Though I hadn’t expected Noel and Litara to sail in, though I had a list of “important” things that needed doing, I mentally re-prioritized plans as I watched them row toward me. I have no qualms about putting everything aside for a day, or even two, to devote myself to doing nothing but enjoying their company.

– – –

Over 45 years, Lin and Larry Pardey sailed the equivalent of three times around the world, visiting 75 countries. They now live ashore on the island of Kawau in New Zealand.