I was 8 years old, and the Vinoy Basin, in St. Petersburg, Florida, was my private kingdom to patrol. Making my rounds, I spotted a skiff barely floating offshore. A few days later, I noticed that it had drifted into the harbor, awash with the tide. The next day, there it was: half-buried in sand in the northwest corner, the one closest to the Flagler-built hotel. It was an honest-to-goodness treasure!

The frayed, sunburned painter told me it had come adrift long ago, as did the barnacles inside and out. There were no markings. But the thwarts were sturdy, the oarlocks stout. It was a 16-foot generic fishing skiff — or, more accurately, it had been a generic skiff, until I started to dream upon it. Two wide athwartship bottom planks were missing, but who was counting?

“Worthless,” my father said when I told him of my find. “Besides, she’s too heavy for a little guy like you.”

“Please?” I asked. Something in the tone of my voice made my father look up and narrow his eyes.

“OK,” he said, “but you’ve got to do the work, not me.”

We were both true to our word.

The following day I scrounged “one-by” wood from every unguarded source I knew. On the weekend, my father carried the saws and planes while I lugged the bits and brace.

“Don’t chop at it,” he instructed me while I sawed. “Just allow the teeth to effortlessly flow. Keep the blade at the same angle. Picture it cutting in your mind. Breathe regular. Use the whole length of the saw. Slow and easy wins the race.”

Getting the planks to fit tightly was difficult.

“Creep up on it, son,” my father advised. “It’s easier to cut again than it is to glue that sawdust back on.”

He held up a bronze wood screw. “You’re going to need exactly the correct bit in your brace. And you’re going to draw the screw threads on that bar of soap I brought to help them turn in. Keep going slowly. If you stop and the screw cools, it might bind and then twist off its head.”

Using the brace and staying perfectly aligned above the holes was particularly challenging.

Once the planks were in place, we had to keep the water out. “Red-lead the seams first,” my father told me. “Then caulk her by sound. I brought several irons and the mallet. Finally, knife on some Woolsey’s seam compound and pray.”

She floated like a swan upon the water.

“She don’t look so worthless now, does she?” I asked him.

He grinned. “No, son, she doesn’t,” he said. “You did good.”

Three days later, she’d swelled up enough to completely stop leaking. Oh, I was proud. “Tight as a drum!” I shouted happily as I rowed her around the harbor.

My father was right on one account: She was heavy and a bear to row, but row her I did. She was mine, all mine. When I finally got through splashing her with paint, she was the prettiest flat-bottom 16-footer in the harbor.

A part of me, 50-plus years later, still loves her deeply.

At age 15, I was living in Chicago and had a plan. I’d save up my money and buy a Volkswagen van. When I turned 16 and had my driver’s license, a pal named George and I would drive to San Francisco for what would turn out to be the Summer of Love. It wasn’t a great plan, but it was a fairly common one for an American youth of that era. But then I was at a hippie Christmas party in an ex-funeral parlor on Cleaver Street (it was an odd period) when I overheard a slightly tipsy sailmaker named Mike Joyce saying: “I’ve got half a dozen sailboats. One is right close by in the Chicago River. I’m going to convert her into a coho fisher!”

A few days later, I happened to be on a bus in snow-snarled traffic on the North Avenue Bridge when I spotted said vessel. It was a lovely William Atkin-designed 22-footer, built in 1932 of Port Oxford cedar. I jumped off the bus. The boat had been broken into and looted. All her ports were smashed. Gang graffiti was spray-painted inside. There was no rig, a fire had been lit in the head area, and the engine was frozen solid with rust.

Like I said, she was lovely.

I sat in the cockpit — gently, so as not to scare her. I felt the most powerful surge of lust I’d ever experienced. I silently told her I loved her and would take care of her and that we’d sail far, far offshore together. Promise. Cross my heart and hope to die. So help me God.

I didn’t have Mike’s phone number, so I called his girlfriend, Lynne Orloff (who would go on to become author of the marine cookbook Can-to-Pan Cookery), and explained the situation. She was a tad taken aback.

“Are you suggesting I, er, withhold my affection from Mike until he sells you that boat?” she asked, appalled. “Great idea!” I said.

Mike and I settled on $200 for Corina, with another $15 for a mainsail and $10 for the jib. “You’re on your way, kid,” he said to me. I believe I’ve proven him correct.

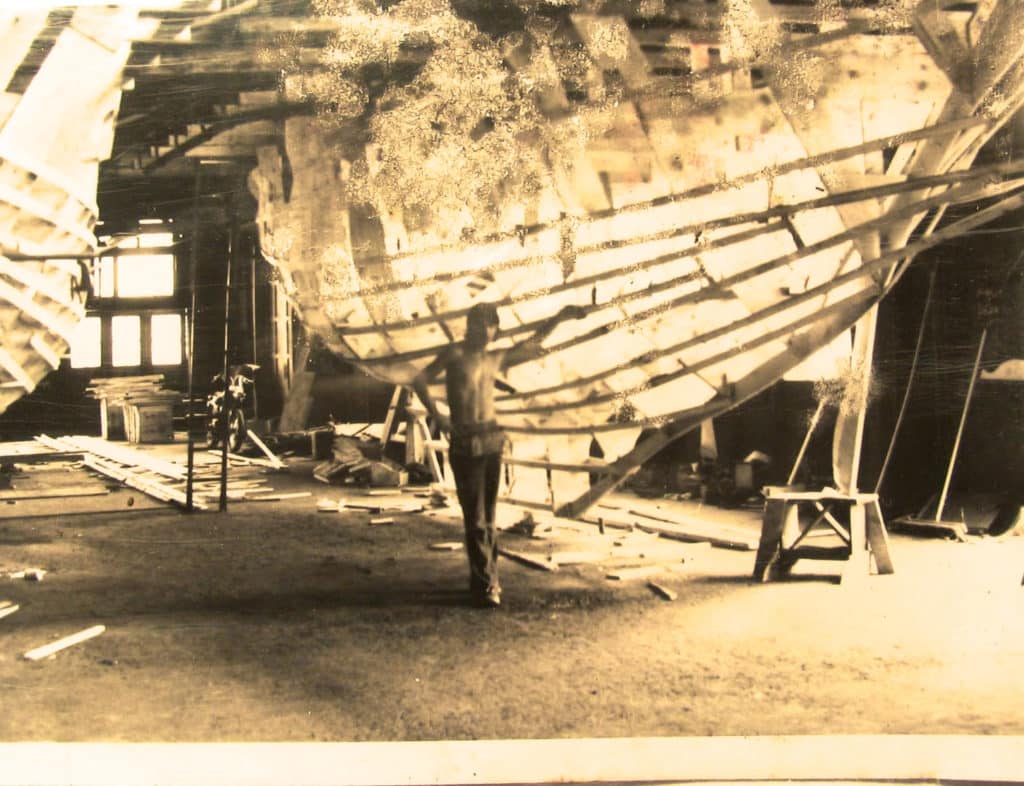

When I reached 19, I put an ad in the Boston Phoenix to see if anyone else was interested in building a bluewater cruising boat. Seventy-some people responded. We had a spaghetti dinner that more than 30 hippies slurped. We picked a couple of dozen freaks out of the pile and formed Ferro Cement Boats of Boston.

Three years later, I splashed Carlotta, our 36-foot Endurance ketch, and arrived in the Caribbean a few years after that. This boat gave me the greatest gift of all. It was not just a home and boat and lifestyle. She gave me the confidence that I could do almost anything if I had my wife, Carolyn, there to help. (Five other boats were built at Ferro Cement Boats, but only the aptly named Perseverance, many years later, saw the water.)

I’d built Carlotta to sail around the world, and she proved a seaworthy, seakindly craft. But rum was 84 cents a bottle on St. Thomas, and life got in the way. Our daughter, Roma Orion, was born. I sailed every regatta on every famous boat in the islands, from San Juan to Trinidad, for over a decade. But at 6:23 a.m. on September 17, 1989, Hurricane Hugo, a Category 4 storm, forced us to swim away from a floundering Carlotta in 120 knots of breeze.

There is nothing quite like wrapping your 7-year-old child’s passport in a plastic bag, duct-taping that plastic bag around her chest, and then jumping into the frothing water with her in your arms.

In the wake of the storm, I was in shock. I was homeless, boatless, penniless, jobless, and farther away from circumnavigating than ever.

I had to shake myself, and shake hard. It was time to get serious about life. Well, as serious as a salt-intoxicated sea gypsy can be.

A few months before the hurricane, a sailor had asked me to survey his boat, a lovely Sparkman & Stephens-designed 38-foot sloop built by Hughes in Canada. Alas, it had been driven onto a reef during the same storm at Mary’s Point, St. John. The owner had nearly drowned in the process, and then decided instead to drown his sorrows in the liquor lockers of all the wrecked yachts surrounding him. The result was that he had been airlifted back to New York City and rehab.

I called him up and offered to help salvage his boat, but he turned me down. “That boat almost killed me,” he said. “I never want to see her again.” “But she’ll just be pounded to bits in the surf and looted as well,” I told him. “So be it,” he said.

I eventually gave him $3,000 for her salvage rights. Once again, Carolyn and I had grinders in our hands and were tackling a project that a sailor with any sense or cents would not be involved in.

What we did have were strong backs and fierce determination. Aboard what was to become Wild Card, we would sail around the world twice, for an initial cost of 4 cents a mile!

We owned Wild Card for 23 years, sailed her almost 100,000 ocean miles, and sold her for 10 times what we paid. But my most powerful memory of her was wading out that first time and wondering if I should bet my entire future on something that had fish swimming inside.

In 2009, we were surprised to find out that the primitive island of Yap had broadband Internet access. This allowed my nerd wife to go off keyboard surfing.

“Did you hear that Jeff at Amazon has invented an MP3 player for books?” she asked. I ignored her, preferring to surf real waves, not cyber ones. But she wouldn’t give up. “Can I contact him and send him some of your writing?” she asked.

“Sure,” I said. “Just leave me out of it, OK?”

Damn it if my nerdy wife didn’t earn us a pile of money — and without me fully understanding what she was doing. Don’t you hate it when that happens?

One day back in the Caribbean, boat fate struck once again. The moment I saw the Wauquiez Amphitrite 43 slumped over in her hurricane hole with a tree branch growing between her mast and forestay, I knew. Her engine was a pile of rust. Her rig was useless. Nothing electric worked. All her running rigging was bright green in the tropical dampness. The spreader lightbulbs hung down like eyeballs out of their sockets. Her dinghy was a deflated mosquito breeder. The fabric of her sails tore easily. There was a major problem with the title, so having her documented in the United States would probably be impossible, which meant no bank was interested in financing her.

Then the story took a turn for the worse. It had been four years since she’d last floated. Looking closer, I saw that a major refitting project was required, one that would demand diverse skills. There was a huge yard bill coming up in 60 days. Rainwater was leaking inside, ruining the varnished interior. The bilges reeked of diesel oil. The rudder didn’t turn, and she was sunk so deep in the mud that we couldn’t see the keel.

Carolyn said, “This boat is almost worthless!”

“Exactly,” I concurred. “Let’s buy it!”

We did, and for $100,000 less than the owner originally had the boat listed for. We tossed in a new Perkins M92B diesel (I make it sound easy; it was not), nailed on a Monitor windvane (ditto), and immediately set off on circle number three before the dirt dwellers and land sharks could get their greedy hooks into us.

Whew!

Each of these boats has given me enormous personal satisfaction for very little money. Basically, we pay for our vessels with sweat instead of cash. Is this difficult? You betcha. Can it be fun? You betcha. Especially since there’s nothing I’d rather do more than mess around with boats with Carolyn at my side. But the real key to my life as a penniless yacht rehabber was that 16-foot fishing skiff and the 22-foot double-ender Corina. Their message was clear: If you’re willing to work harder and smarter than the next fellow — and you’re married to Carolyn — damn near anything is possible.

Fatty and Carolyn are currently preparing to cross the Indian Ocean on Ganesh, their 43-foot Wauquiez Amphitrite ketch.