Sails do not last forever, but with proper care, cruising sails made of a high-quality Dacron sailcloth will provide many years of service. I know this because I spent more than 70 years maintaining sails, often turning for advice to Graham Knight, of Antigua Sails, who has been repairing sails in Antigua since 1970. Knight has repaired or supervised the repairs to more sails than anyone else I can think of.

My sailing career began in the days of cotton sails and manila or linen running rigging. It was a good school in which to learn how to repair sails, as there were few sailmakers in the Caribbean in the late 1950s, just a few locals who made or repaired canvas sails entirely by hand. We yacht owners did most of our own sail maintenance, also by hand.

When Dacron sails first arrived on the scene, we thought it was heaven. Dacron was unaffected by changes in moisture. Gone were the days of having to carefully ease the halyard and outhaul as you sailed into a fog, or when rain soaked the sail. Gone were the days of carefully drying sails to make sure they did not get mildewed, and we could forget about putting on the sailcover to keep the nighttime dew off the sail. I did, though, miss the most comfortable place to sleep in a boat: curled up on a dry cotton spinnaker in the fo’c’sle.

Over time, we learned from experience that Dacron sails become damaged in three ways: as a result of weak stitching, from flogging, and by degradation from exposure to UV radiation from the sun. The stitching was a particular weakness in those early Dacron sails, in part due to the sensitivity of the thread to UV exposure.

A Stitch in Time

I quickly learned that when the stitching fails, a sail will split from the leech in, seldom from the body of the sail out. If on Iolaire we noticed a seam opening up in the body of a sail, my crew or I would restitch it by hand at the end of the day. If a seam started to fail from the leech in, it would split all the way to the luff before we could get the sail down. I vividly recall spreading a mainsail across the fuel dock at Yacht Haven in St. Thomas, restitching by hand where it had split from luff to leech — two rows of stitches, each 15 feet long. That taught me to regularly inspect the leech of every sail and restitch the weak points before they failed.

Just before my late wife, Marilyn, and I decided to emigrate to Grenada, I acquired a heavy-duty Pfaff electric zigzag sewing machine mounted in a proper table. We disassembled it and packed it in Iolaire’s port pilot berth so it would be on the windward side going to Grenada. Periodically, I set up the sewing machine in the bar at the Grenada Yacht Club, where I could spread the sails out. I regularly restitched them along the leech and along the seams to 3 feet in from the leech. I did the same along the foot of the high-cut yankee. That ended the weak-stitching problem for Iolaire.

Take it from me, you will substantially increase the life of your sails by periodically taking them to a sailmaker who can inspect them, make any obvious repairs and do as I have described above. Also, have the batten pockets restitched if the stitching looks weak.

Once a sail is two or three years old, it will become apparent where it chafes on shrouds and spreaders. Have your sailmaker glue on reinforcement patches in the way of the spreaders and narrow strips over the seams where they chafe on shrouds. Taking these simple steps will lengthen the life of the sail considerably.

Knight recommends you persuade the sailmaker to use Gore Tenara thread when you have your sails restitched. Sailmakers do not like to use it because it is expensive and the machine must be specially set up for it, but the thread will last longer than the sail.

Shaken to Pieces

Flogging is another major cause of sail damage or destruction. In the days when Iolaire had cotton sails, I had a lot of trouble with the batten pockets or the sail under them tearing when the sail flogged during a tack or when reefing. When I ordered my first Dacron mainsail from Charlie “Butch” Ulmer, I asked for a battenless main. This eliminated the problem of broken battens, and battens fouling in the rigging when sails were hoisted or doused, but introduced another: I always had a fluttering leech unless the leech line was pulled taut, and then I had a curled leech.

When the battenless main was coming to the end of its life I replaced it with a main with battens. To keep the wooden battens (plastic battens did not yet exist) from breaking and tearing the batten pocket or sail, I installed three very thin battens in each pocket. The thin battens would bend more without breaking than a single thicker batten. I also removed the batten pockets, sewed a patch under each pocket, then reinstalled the pockets. As a result, if a batten did break and tear a hole, because of the double thickness, the hole was usually in the batten pocket rather than in the sail. A hole in the batten pocket was much easier to repair than a hole in the sail.

The problem of the flogging mainsail was solved in 1989, when Robbie Doyle gave Iolaire a fully battened mainsail with one of his first StackPacks. I will not get into the debate about which sails are faster, but from the cruising sailor’s standpoint, a fully battened sail beats the battened soft sail six ways to Sunday. A fully battened sail does not flog when it’s being reefed. If a squall approaches and the skipper feels it will only be a brief one, the main can be eased so it’s completely depowered but will not flog. It may take some strange shapes, but it will be depowered. It can be retrimmed once the squall has passed.

We discovered a few problems with the Doyle StackPack as originally conceived, but we sorted them out over time. A fully battened sail installed in a StackPack or a similar cover will last virtually forever.

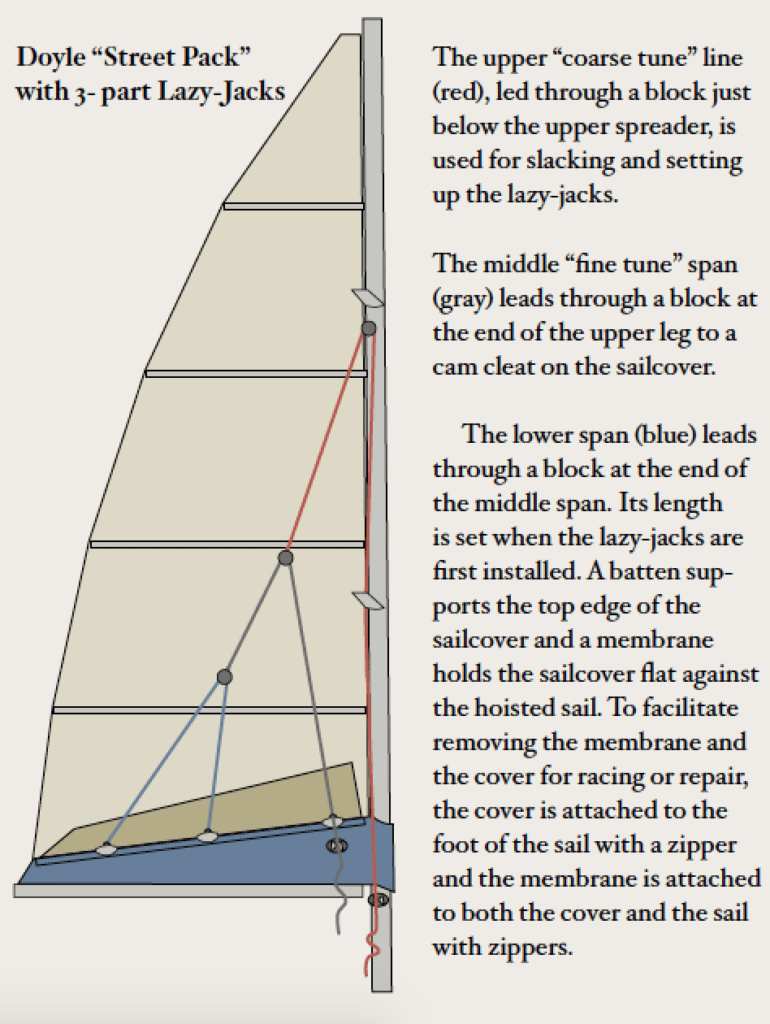

After six hard seasons in the Caribbean and a transatlantic passage, I replaced Iolaire’s original StackPack with a Street Pack — a Doyle StackPack installed with zippers (see “From StackPack to Street Pack,” page 85). I replaced it not because the sail was worn out but because the cover and the membrane were falling apart and, being all sewn together, were too difficult to repair. Since then, the cover and membrane have been removed and repaired three times, but the sail was still going strong when I sold Iolaire 17 years later!

Many sailmakers make their own versions of the StackPack. Before ordering one, make sure the sail, cover and membrane (if fitted) are all connected with zippers rather than being sewn together.

UV and Polyester

We discovered the hard way in the tropics just how susceptible to rapid degradation polyester fabrics like Dacron are when exposed to UV rays. Knight showed me how to determine how severe the damage was. He pushes a sail needle through the cloth. If it goes through cleanly, all is well and the sail can be restitched and repaired. But if the needle goes through the material with a pop, the cloth is toast.

We also discovered that the light, easily handled Dacron sailcovers were not the answer; they did not protect the sails from UV damage. The solution was to make the covers out of mildew-proofed Vivitex or, later, Sunbrella. The life expectancy of boom-stowed sails on all rigs was greatly increased if the crew put on the sailcovers every day as soon as the sail was dropped. The StackPack took care of the UV problem to a great extent, on Iolaire’s mainsail anyway. Headsails were another matter.

On Iolaire, we fought the problem of UV degradation on roller headsails for 50 years. In 1961, I installed a jib and a staysail that roller-furled on their own luff wires. We made them work by setting them up on two-part halyards led to a winch. The luff wires were the same diameter as the stays, and we tensioned the luff wires until the head and staysail stays were slack. The system worked well, but the sails were all the way out or all the way in. To minimize damage from UV rays, any time we would not be sailing for two or three days, we lowered the sails and stowed them coiled in bags.

Eventually, the leech and foot of the yankee, which remained exposed when the sail was furled, were shot. The body of the sail was fine, so my crew and I laid out the sail and removed the luff wire. I then had a sailmaker cut 18 inches off the leech and foot and rebuild the head, tack and clew corners. My mate and I shortened the luff wire to suit the new luff length, fed it through the sail and tensioned it between two palm trees with a four-part tackle. We then adjusted the luff tension of the sail, secured the head and tack cringles to the ends of the wire, and secured the sail to the luff wire. We now had a good J2 and bought a new J1.

This same operation, cutting the sunburned material from the leech and foot of a high-cut jib, can also be done on a genoa, reducing a 150 percent genoa to a 135. With headsails fitted to a roller-reefing foil, this operation is much easier than with the old sails with luff wires.

Roller Reefing

In 1986, Olaf Harken offered me a very good discount on Harken’s headsail roller-reefing gear. From the late 1960s to the ’80s, bent-up and broken-down roller-reefing headsail gear was stacked like cordwood in rigging lofts across the Caribbean, so despite the limitations of my roller-furling headsail rig, I was not at all interested in switching to a roller-reefing headsail on a foil.

What Harken really wanted was for me to test his company’s new gear for larger boats. When he offered to give me the gear and a headsail to go with it, I accepted. The gear worked perfectly for nine hard years in the Caribbean, three transatlantics, 17 years cruising and racing in Europe, and was still going strong when I sold Iolaire.

In one way, though, it was a step backward. To protect the sail from UV rays, we removed it whenever we were not sailing for any amount of time. With the headsail it replaced, one person could slack the halyard, drop the sail and, with some difficulty, coil the furled sail into its bag. By contrast, removing the big yankee from the headstay was a three-person job, as was hoisting it. Thus we did not do it with the frequency we had with the roller-furling sails, and the sail suffered.

To eliminate the sunburn problem, many cruisers have a protective layer of Sunbrella about 18 inches wide sewn on the leech and foot. It looks like hell and does not improve the set of the sail. The better solution for a roller-reefing headsail is a cover of the kind I first saw on German yachts in the Baltic in the late ’90s and is now becoming common elsewhere. The cover, which is a long sleeve, is hoisted, usually with the spinnaker halyard, then tightened with a lanyard threaded through a series of hooks and eyes. It covers the sail completely and does not flap in the breeze. However, friction imposes a limit as to how big a sleeve can be made and still be practical to hoist and douse. Knight says the maximum practical luff length is about 60 feet. A sail with a luff any longer than 60 feet is too big to regularly take down when the boat is not being sailed, so it is left up and the leech and foot remain exposed to UV rays. Some skippers, rather than use a colored protective material, have sacrificial strips of cloth the same color as the sail sewn on the leech and foot. Mark Fitzgerald, the longtime skipper of the 115-foot high-tech ketch Sojana, coats the leech and foot with white emulsion paint, which has proved to minimize UV damage. North Sails has a liquid “ink” that reduces UV damage. It is available in several colors and can be sprayed on existing sails if they are clean.

Be sure when you furl your sail on a roller furler that the drum turns in the direction that leaves the Sunbrella cover and not the sail itself exposed.

I have been told by Evelyne Nye, head of Custom Canvas and the North Sails agent in St. Thomas, that the best headsail covers are made by Etienne Giroire, a French singlehanded racing skipper who does business as ATN (atninc.com). This certainly looks like the solution to the UV problem with roller-furling headsails.

With diligent care, Dacron sails can be made to last a good long time: Don’t let them flog, inspect and restitch vulnerable areas on a regular basis, and protect them from sunlight.

– – –

Voyaging legend Donald M. Street Jr. has been racing and cruising on both sides of the Atlantic — and writing about his exploits — for over five decades.