The sheer number of battery chargers and combination charger/inverters available to boatbuilders and owners is daunting. How do you select the right one for a given vessel and crew? Fortunately, when you break down the list by capacity and features, the selection process is actually relatively easy.

In order to select the right charger for your vessel’s battery bank(s), begin by determining your goals. Ask the following questions: Under what conditions will the charger be used? If your boat mostly remains dockside and you wish to keep batteries topped up and a DC refrigerator running, with the juice to run bilge pumps should a leak develop, that’s one thing. Using the charger with a generator, to replace house bank amps in bulk after long periods of discharge, is another.

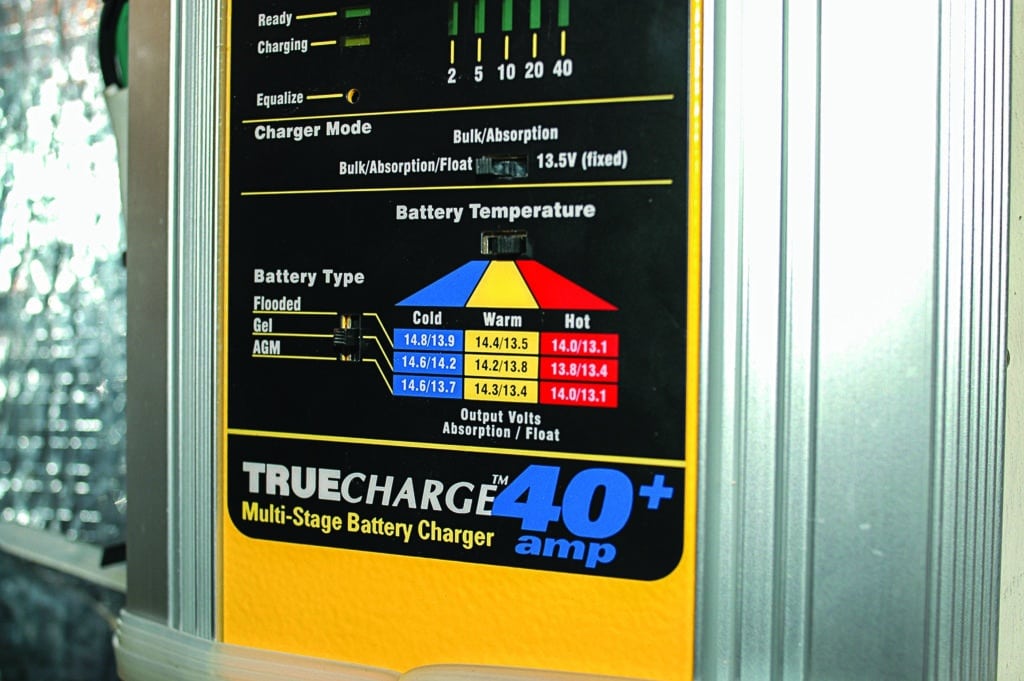

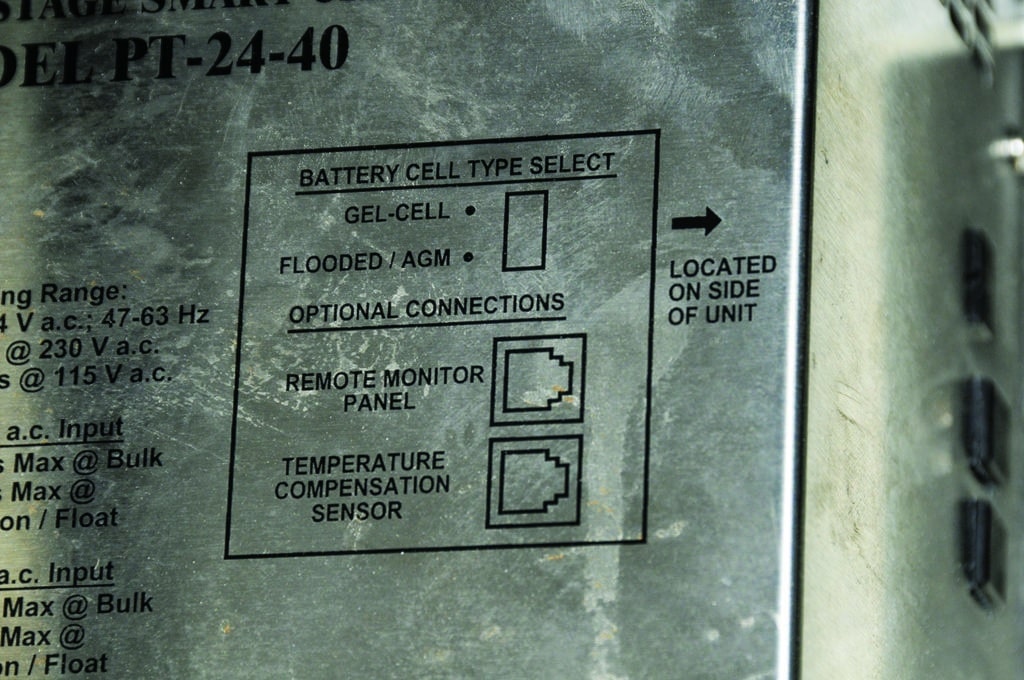

Will it be used to charge a single battery bank or multiple ones? Do you want at-the-battery temperature compensation and remote voltage sense capability? Both features are valuable, especially concerning sealed valve-regulated lead acid (SVRLA) batteries — which encompass both AGM and gel models. Do you want a charger that has the capacity to equalize batteries, using an intentional, controlled overcharge to resurrect a battery bank that’s lost some of its capacity?

Today, most battery chargers offer multistep charging (bulk, absorption and float, and equalizing if desired). Consider that a prerequisite. Multistep charging typically affords more rapid charges and is easier on batteries, extending their life span.

Remote (as opposed to local or inside the charger) temperature compensation is well worth the added expense, as is remote voltage sensing. Both features enable a charger to more effectively tailor its charge profile to the battery bank’s needs. Cool batteries can accept more current, and recharge more quickly than hot batteries; however, if the charger can’t determine the temperature, it can’t adjust its output accordingly. Also, the voltage at the batteries may be different from the voltage the charger is sensing at its output, making remote voltage sensing desirable. Once again, it allows a charger to more accurately adjust its output to suit the batteries’ state of charge.

If you’ll rely on a charger to restore a depleted house battery bank via a generator — an approach that often makes sense for generator-equipped vessels that are also operating other AC-powered gear — it should be sized accordingly. For conventional flooded batteries, assume they can accept no more than 25 percent of their amp-hour capacity during an initial charge. Thus, a 400 Ah battery bank would be limited to 100 amps; any more simply couldn’t be digested. For gel batteries assume 50 percent, and for AGMs assume 100 percent. The latter two battery types are desirable, among other reasons, for their ability to recharge quickly. This characteristic also favors larger chargers.

If, on the other hand, the charger will simply be used to maintain house and start banks while the vessel is dockside, far smaller units can be used. These are typically in the 20- to 40-amp range, more than enough to float these batteries.

Flooded and some AGM batteries are capable of being equalized, with limitations. This feature can be a lifesaver (or at least a money saver) if a bank becomes severely depleted and forms power-robbing sulfate deposits on its plates. Sulfated batteries often lose significant capacity, making them all but unusable.

Finally, make certain that positive cables that connect chargers to batteries are overcurrent protected: Use a fuse or circuit breaker at the battery, rather than at the charger. This should be within 72 inches if the wire is supplemented by a sheath or in a conduit, or 7 inches if it isn’t. The mission of overcurrent protection is to shield the wire from overheating in the event of a short circuit; it’s not designed to protect the charger, which has its own internal protection.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting (www.stevedmarineconsulting.com).