Ask six manufacturers where marine electronics are headed, and you’ll usually get six different answers. That wasn’t the case last fall, however, at the 2015 National Marine Electronics Association Conference and Expo, where the industry buzzword was straightforward: “integration.”

Not so long ago, the “wired” sailboat might have sported a GPS; instruments displaying wind, speed, depth and engine data; a stereo; possibly an AIS monitor; and maybe additional gear at the nav station down below, all with their own screens and knobs.

Today those stand-alone devices are quickly disappearing, and in their place, manufacturers are rolling out networked instrumentation packages that can increasingly combine data feeds and display the results on a variety of screens, both on your boat and in your pocket.

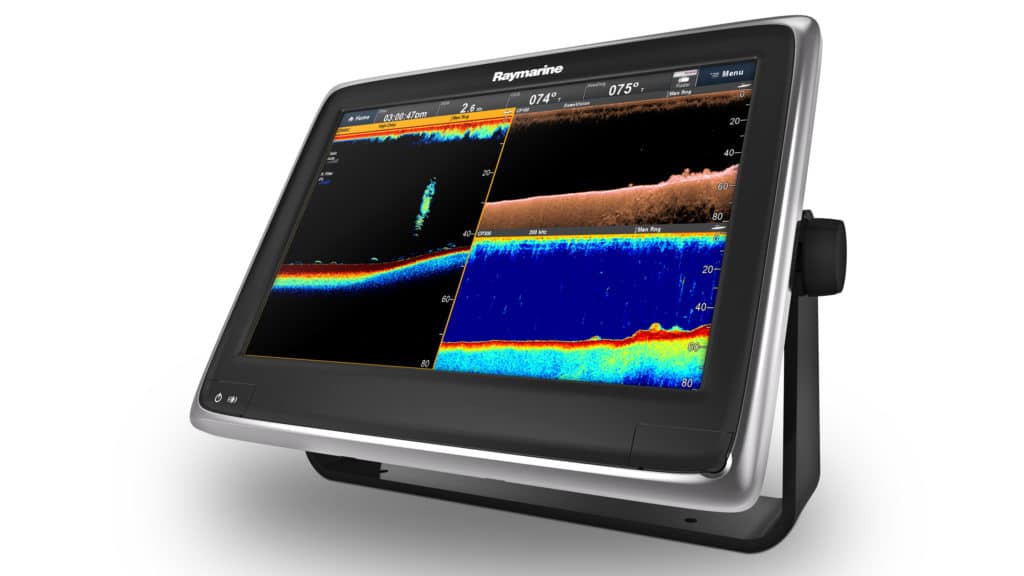

Typically these systems employ sensors that talk to dedicated black-box modules, which are in turn networked to share information with a multifunction display that now sits at the heart of the network, disseminating that information to other devices as needed.

Examples of this integration include performance-sailing packages, cameras and other video devices, and a growing array of sounders. Together, they can tell you where you’re going and what the route ahead and below looks like, as well as keep you company in the cockpit on a long night’s watch.

The biggest development, aside from information-sharing protocols like NMEA 0183 and NMEA 2000, has taken place within the world of MFDs, with both dramatically improved user interfaces and greater processing power. In each case, MFDs have directly benefited from the rise of high-end smartphones and tablets in the consumer-electronics market, which use touch-screen interfaces and demand lightning-fast processor chips. Moreover, smartphones and tablets have helped everyone quickly learn about and feel at home with touch-screen and app-based software. The net result is that today’s MFDs are far more capable than chart plotters and displays from even five years ago. “We’re seeing more features that are built into MFDs as standard equipment,” says Jim McGowan, the U.S. marketing manager for FLIR and Raymarine. “Years ago, this all required individual modules, which added to the costs.” Now, he adds, this functionality is integrated into the MFD. “All the core features are there, but they’re less expensive for the customer.”

McGowan says this cost-savings is the result of higher manufacturing volume; the influx of high-end, off-the-shelf tablet and smartphone processors; and the standardization of MFD hardware. In other words, the components in various product lines are identical, with different levels of software providing increased levels of functionality.

“MFDs are getting more development than anything else,” says McGowan. “They are the key focal point for navigation — and sometimes entertainment — so we want to make a user’s experience as simple as possible.” Other experts agree. “Everything connects back to the MFD,” says Marc Jourlait, deputy CEO at Navico, which is the parent company of B&G, Go Free, Lowrance and Simrad. He believes today’s marine electronics have to be easy to use, and pushing information to the cloud has to be a simple task. “There are so many opportunities to make [electronics] better and more seamless,” he says, describing the challenges manufacturers are tackling. While pushing data to the cloud depends on Internet connectivity (more on this in a minute), one way contemporary MFDs simplify the user experience is through customizable screen views. Depending on the display, these views can often be created by dragging and dropping app icons onto one of several screen-layout templates. With a swipe of a finger, a user has the ability to control and monitor networked fixed and handheld cameras, determine the content viewed in split screens, display television and video imagery, and even control the stereo.

As MFDs become increasingly important to a boat’s operations, some manufacturers have begun building smaller, fully marinized smart displays to augment them, including B&G’s Vulcan sailing chart plotter, Garmin’s GNX 120 and 130 large-format marine instruments, and Sailmon’s line of performance-oriented smart displays. In the case of B&G and Garmin, these new screens complement the boat’s main MFD, allowing sailors to spec a full MFD at the nav station (and possibly a second MFD at the helm) while installing a few of the smaller displays on deck for specific purposes.

Sailmon takes a different tack with its Model X and Model VII smart displays, which replace an MFD with a networked PC that’s running Expedition software (as well as a networked black-box module that interfaces with various onboard sensors, instruments and networks).

In all cases, these new devices eliminate the need for dedicated instrument displays such as outmoded depth sounders or anemometers, and provide a huge amount of flexibility when it comes to displaying germane information both in graphical and numerical formats. They also offer robust system redundancy.

While powerboaters continue to represent the bulk of the marine-electronics market, several MFD manufacturers are now bundling their systems with sailing-specific features and functionality (see “Meet Your Electronic Tactician,” January 2016). This trend, which B&G pioneered in 2012 with its SailSteer wind-rose icon, is now gathering considerable momentum, with Garmin and Raymarine also offering similar capabilities. All three manufacturers boast advanced, graphically rich sailing features that include starting-line assistants, laylines and wind roses. And while the starting-line software is of little use to the pure cruising sailor, laylines and graphical wind roses are great examples of performance-sailing software that can directly help any helmsman sail more efficient courses and increase big-picture situational awareness. For example, B&G’s software calculates its estimated arrival times based on how long it will take the boat to sail to a given waypoint, layline or destination tack by tack, as opposed to a straight-line time-over-distance calculation.

While these sailing-specific features are fairly new, users can expect more development in this field. “We’ll have more sailing-specific features coming in 2016,” says Dave Dunn, Garmin’s senior manager of marine sales and marketing. “We’re going really hard at the sailing market.”

Garmin acquired Nexus Marine AB in 2012 and is rolling out Garmin-branded products that are heavily influenced by Nexus’ line of racing electronics, including the GNX 120 and 130 large-format marine instruments. Dunn says consumers should look for more sailing instrumentation packs and separate sail kits that are designed to make things easier for the navigator-helmsman.

Depending on the manufacturer and model, added sailing-specific functionality and other features often come in the form of software updates as opposed to hardware upgrades, thus adding value for MFD owners and eliminating the need to constantly buy new devices.

As in the broader consumer-electronics market, marine-electronics manufacturers are also adopting wireless technology, albeit at a slower clip than land-based electronics manufacturers. Given the amount of trust that sailors place in their onboard electronics, it’s understandable that manufacturers have historically embraced hardwired connections for critical instruments such as radar, autopilots and GPS, but this attitude is starting to change as manufacturers (and customers) gain confidence in onboard Wi-Fi.

A prime example is Furuno’s DRS4W 1st Watch Wireless Radar, which debuted last winter, and which wirelessly shares its imagery with Apple iOS devices rather than a dedicated display. “Wireless is of interest to all, but so are safety concerns,” says Matt Wood, Furuno’s national sales manager, who suggests that more Wi-Fi radars are on the not-so-distant horizon. “There’s a fear about how far Wi-Fi should go. It’s important to embrace Wi-Fi, but also to remember its limitations and ensure safety.”

Other experts see wireless instrumentation and sensors as a natural evolution. “I foresee that everything will go wireless, but it’s a personal opinion,” says Dunn, who’s careful to exclude radar and sounder transducers, which he deems to be mission-critical, from the list of wireless candidates. “Telematics will take over, allowing owners to call in and check their bilge levels. That’s the future.”

Navico’s Jourlait says the “smart boat” is the future, especially as people get comfortable with smart household systems that are digitally controlled by apps, smartphones and tablets — the so-called Internet of Things.

Meanwhile, across the marine space, traditional boundaries that defined what sort of mariner used a particular piece of gear are breaking down. Sonar, for instance, was traditionally found on powerboats, not sailboats, but this is changing with forward-looking sonar technology — including B&G’s ForwardScan and Garmin’s Panoptix Forward Transducer. This gear hit the market in mid-2015 and now gives sailors the ability to see what lies ahead in a coral pass or harbor entrance. While the technologies behind these products are different, both aim to increase a sailor’s situational awareness and are reportedly already being used by sailors to wend through ice and tight, rocky passages.

Digital-switching systems — already entrenched on the powerboat side — have also emerged as a fast-moving trend on new sailboats. These systems are often significantly lighter and easier to install than their hardwired rivals. “Digital switching is growing all around,” says McGowan. “Builders can save several grand by installing digital switching, as copper wire is expensive.”

Some manufacturers believe modern MFDs can serve as the user interface for a digital-switching system that controls all a vessel’s functions, but not all are sold on the concept.

Wood says Furuno is looking at digital switching, but so far the company remains skeptical of the ability of an MFD to control such a system. “There are a lot of traditional sailors who don’t want navigation and switching combined,” he says. While integrating digital-switching systems and wireless instrumentation and sensors is contentious to some, everyone can agree that having access to up-to-date information allows sailors to make better, more informed choices. To further this goal, most MFDs are now equipped with built-in Wi-Fi, both to facilitate information-rich Wireless Local Area Networks and to allow the MFD to go online when connectivity exists — say, at a marina — to do myriad tasks, including chart updates and sharing crowdsourced information.

The bottom line:

Cruisers are already benefiting from faster, more capable and less expensive MFDs that come loaded with sailing-specific features, especially as manufacturers compete with one another over this market share. Thanks to current market trends such as wireless connectivity, smart devices and digital switching, odds are good that sailors can look forward to increasingly sophisticated interfaces that will be easier to use, but will also help ensure the safety of their vessel both at the dock and underway.

David Schmidt is Cruising World’s electronics editor.