Most everyone is familiar with the ubiquitous ground fault circuit interrupter, or GFCI receptacle. Among other locations, they’re found in household kitchens, bathrooms, patios and garages. They’re also recommended by the American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) for use in heads, galleys, engineering spaces, and on the weather decks of boats. Since their introduction in the late 1960s, they have no doubt saved countless lives. Requirements for GFCIs have been part of the National Electric Code for more than 50 years, with the first mandate being inspired by electrocutions caused by underwater lighting used in swimming pools.

While GFCIs have been widely covered, there is yet another shore-power safety device, one that was introduced to the marine market only within the past decade, that’s also worthy of attention. Referred to as an electronic leakage circuit interrupter, or ELCI, it offers yet another level of protection from shore-power faults, fire and electrocution. Much like a common GFCI receptacle (these have a comparatively low trip threshold of 5 milliamps, and as such are considered to be appropriate for protecting people), ELCIs remain in a state of equilibrium. As long as the current on the hot and neutral wires (the two current-carrying conductors found in most AC electrical circuits) remains the same, they allow energy to flow. As soon as current finds an alternative path back to its source — through a green safety ground wire, the water or a person — the imbalance trips the ELCI’s circuit breaker and the power is turned off nearly instantly, often within 30 to 70 milliseconds. (Contrary to popular belief, electricity does not seek ground; it seeks to return to its origin, like the transformer at the head of the dock.)

While technically deemed “equipment protection” because of their 30-milliamp trip threshold, the goal of ELCIs is to interrupt current flow quickly enough to prevent electrocution, electric-shock drowning or fire — and for the most part, they do so quite effectively, saving countless lives every year.

As it was with the GFCI, the adoption of the ABYC ELCI standard was inspired by a number of electric-shock drownings, or ESDs. An ESD is different from a conventional electrocution; with comparatively little current flow, it can paralyze a swimmer’s voluntary muscle reflexes, causing the victim to drown, which can mask the underlying electrically related cause of death.

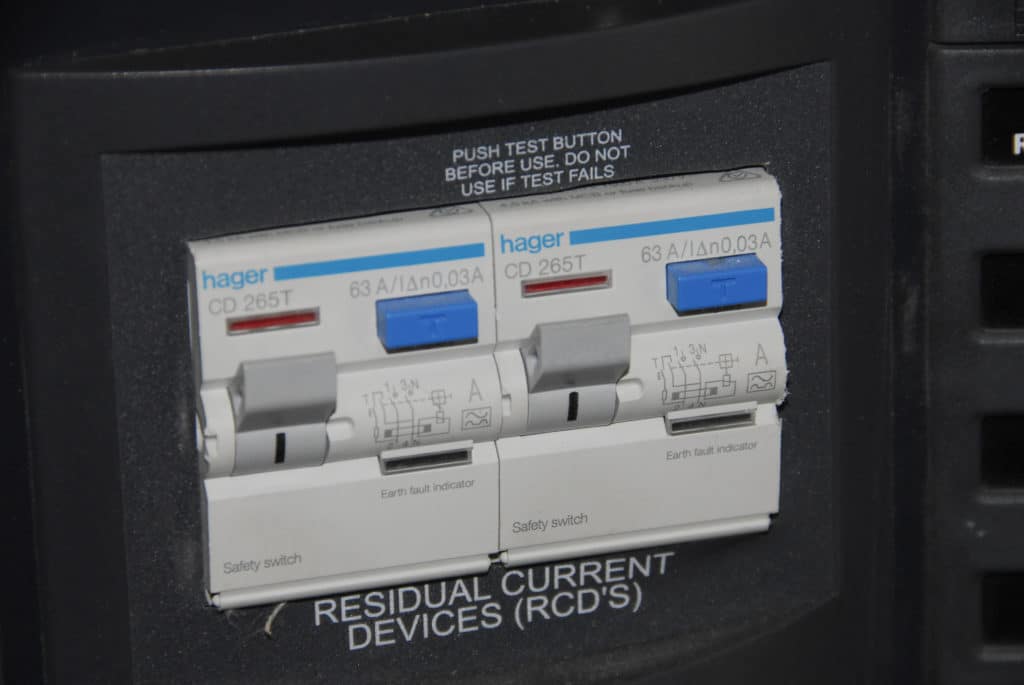

In addition to the trip threshold, the primary difference between the ELCI and the GFCI is the location in which it is installed. GFCI receptacles are installed where power is to be used, like the galley, head and so on. ELCIs are installed where power enters the vessel, near the shore-power receptacle. Think of it as a “whole boat” GFCI with some modifications. A primary shore-power circuit breaker is already required for every shore-power inlet, and in the case of an ELCI, it is often installed either in conjunction with this breaker or as a single combined unit, achieving the goals of overcurrent protection and fault protection. It’s important to note that the presence of an ELCI does not negate the need for individual GFCIs; both are still required for ABYC compliance.

ELCIs got off to a rocky start when they were first introduced in 2008. As is often the case, good intentions preceded the hardware with the ability to facilitate them; as a result, the implementation was postponed for a couple of years. Now, however, ELCI circuit breakers are readily available from several manufacturers in a range of configurations. With a few exceptions, new vessels or those that are being refit to ABYC standards must be equipped with ELCIs, and with good reason: They save lives. An ELCI can be added to virtually any vessel’s shore-power system provided it is free of faults.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting (stevedmarineconsulting.com).