As the old saying goes, water and electricity don’t mix, especially aboard a cruising vessel. Even the best-designed and -installed electrical systems can come to grief if left to their own devices; the damp, salty environment virtually guarantees it. If you haven’t suffered an electrical failure, you simply haven’t cruised long enough. That said, in my experience the vast majority of failures are entirely avoidable. Let’s take a look at a few of the more likely examples.

Improperly installed solderless or “crimp” connections: When properly installed, high-quality solderless terminals are extremely reliable; millions of them are literally in flight at any given moment aboard civil and military aircraft. However, using terminals that don’t match the wire size, or ring terminals whose hole is larger than the fastener over which they are placed, or terminals that are improperly compressed all account for a large percentage of the electrical failures I encounter. Use nylon rather than PVC-insulated terminals, along with high-quality crimping tools, and make certain you know how to use them.

Direct-bearing terminals: Guidelines established by the American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) prohibit the use of screw terminals that bear directly against wires. Such terminals are commonly found in household or industrial electrical applications, where they are used with rigid solid wire. The wire used aboard boats, referred to as “boat cable,” is quite the opposite; stranded and pliable cable, while less prone to stress failure, is ill-suited for direct-bearing screw terminals. When used with direct-bearing screw terminals, stranded boat cable is often crushed and damaged, which causes it to loosen, arc or separate from the terminal. Only indirect-bearing terminals should be used with boat cable. If the use of a direct-bearing terminal is unavoidable, the wire should be terminated with a pin terminal.

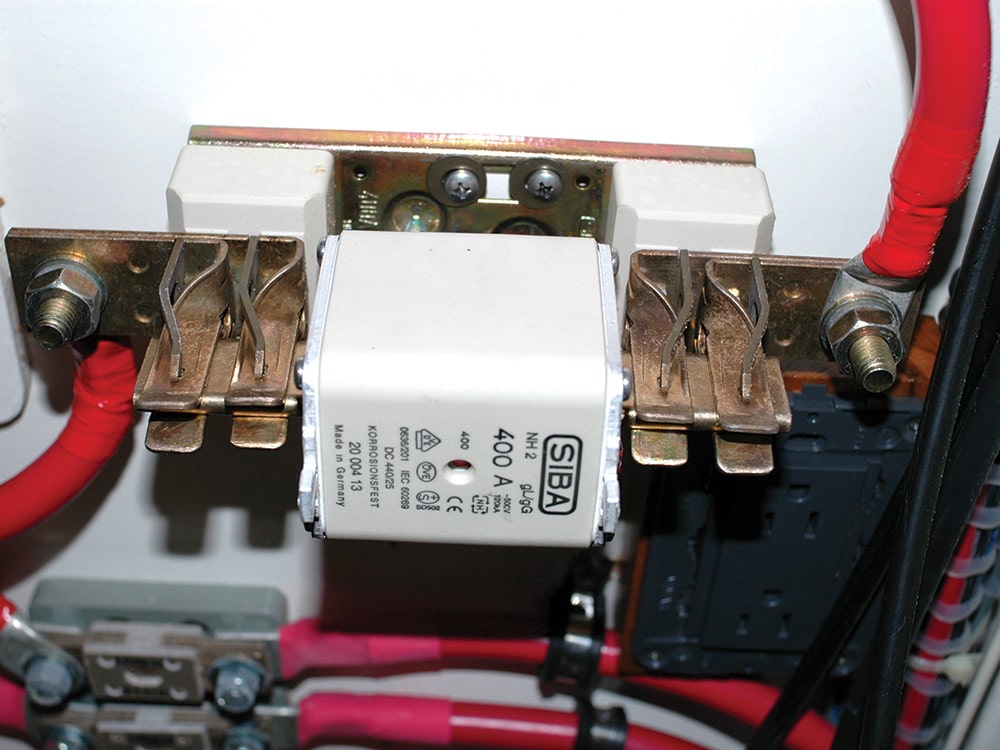

Lack of over-current protection: What about fuses and circuit breakers? For DC wiring, every wire connected to every battery’s positive terminal must be protected by a fuse or circuit breaker located within 7 inches of the battery terminal. This can be extended to 72 inches if the wire is protected by additional insulation or is within a conduit. The only exception to this rule is cabling for engine and genset starters, which are exempt from the over-current protection guideline. This guideline also holds true for smaller wires that are connected to secondary sources of power that are supplied by larger cables, such as starter positive posts, battery switches and bus bars. For AC or shore power/genset/inverter wiring, over-current protection must be located, once again, within 7 inches of the power source. That distance can be increased to 40 inches if the wire is additionally insulated or contained within a conduit.

Exposed energized connections: Ungrounded terminals, junctions and bus bars must be insulated or enclosed. For DC terminals, the risk is a short circuit (think of an aluminum boat hook falling against an ungrounded terminal and a seawater strainer or engine block). In the best-case scenario, it blows a fuse or trips a circuit breaker. In the worst-case scenario, it leads to a fire. In the case of AC wiring, an exposed hot terminal is a short circuit, fire and electrocution risk. Every hot AC terminal or junction should reside within a dedicated electrical locker (behind a fastened or locked circuit-breaker panel), or within a purpose-made junction box.

Corrosion: Assume that at some point every electrical connection will get wet — if not doused, then at least by a briny mist. Ideally all terminals, terminal blocks, bus bars and studs should be tinned. While it’s not required for ABYC compliance, wiring should also be tinned. For those items that aren’t tinned, coating with a corrosion inhibitor (I prefer CRC Heavy Duty Corrosion Inhibitor) is a must.

Even for those that are tinned, in engine compartments where a seawater hose or pump may leak, and in bilges, chain lockers and lazarettes, coating with corrosion inhibitor makes good sense.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.