On passage, as long as there are 12 knots of true wind, a combination of wind and water generators will reliably churn out 200 or more amp-hours per day (APD) at 12 volts. To produce this amount of power via the engine’s alternator or a generator would typically require running it for four to five hours a day.

The first practical wind generator was developed by the late Hugh Merewether, a retired Hawker Siddeley pilot. He reached Grenada in 1973 with a small wind generator mounted on the face of the mizzenmast of his Nicholson 38, Blue Idyll. Since Blue Idyll had an engine, he never really knew how many amps per day the unit produced.

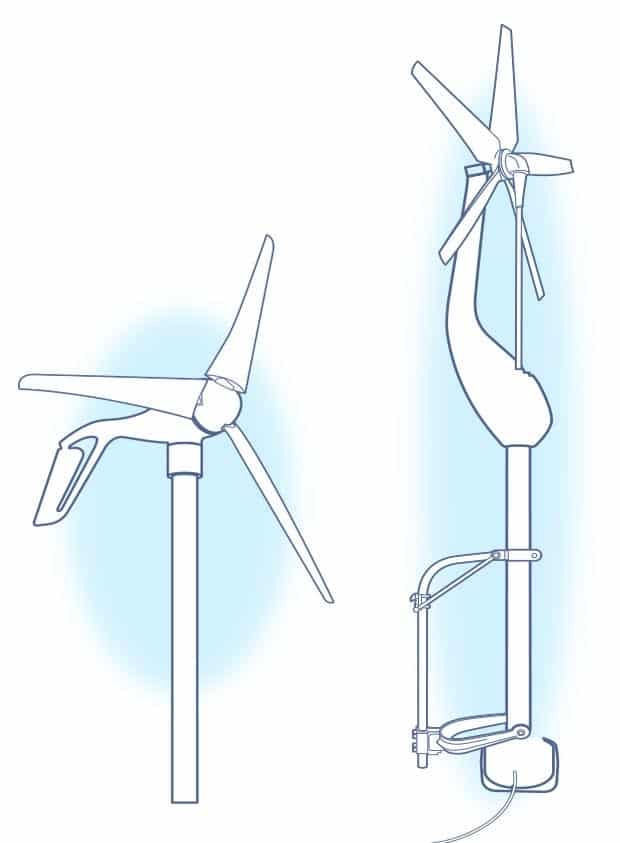

In 1975 I persuaded Hugh to lend me the wind generator to see if it would produce enough APD to run the lights aboard Iolaire, my 1905 46-foot engineless yawl. He mounted the wind generator on Iolaire’s mizzen masthead so it would be as high as possible and allow me to use the mizzen staysail. That year Iolaire did a double transatlantic, along with the Fastnet, La Rochelle, La Trinité, and the Bénodet and Solent races. Iolaire arrived back in Grenada having sailed 13,000 miles in seven months with the wind generator providing enough APD to run her lights. This proved to Hugh that he had, with development, a commercial proposition. Hugh and the British company Ampair developed the Ampair 100, one of which was on Iolaire’s mizzen masthead from 1977 until 2008, when Ampair gave me one of its new 300-watt wind generators.

The 100 gave me 31 years of silent, trouble-free service. It went through many gales, three storms blowing 70 knots, and one hurricane. In the storms and hurricane, the wind in the rigging gave more noise than did the wind generator. Its 300-watt replacement begins to give an audible hum at 40 knots, at which time it is electrically locked off.

On Iolaire’s double transatlantic, I realized that as long as the wind was abeam or forward of the beam, the wind generator produced enough APD to run Iolaire’s lights. Downwind, however, since the apparent wind drops off, the output of the wind generator would also drop off, to the extent that Iolaire at times had to revert to kerosene lamps belowdecks.

When that Merewether generator was replaced by the Ampair-developed 100, I cannibalized the original and assembled bits and pieces from an Antigua slipway junk pile, inventing a water-powered taffrail generator.

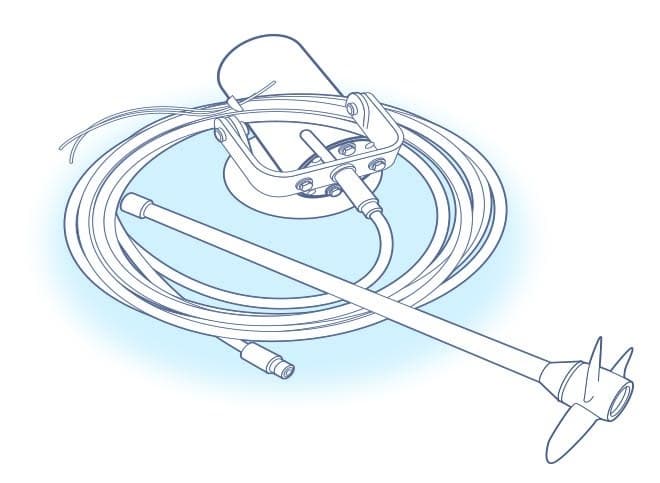

I proved that it worked on a sail from Antigua to Grenada and then showed it to Hugh. Ampair developed the idea into the Aquair 100, a unit that produces 144 APD at 7 knots with only 24 pounds of drag, measured on a spring scale.

Today, with wind and water generators, there’s no excuse for boats on passage to use engines or generators to charge batteries. Engineless Iolaire has made five transatlantic passages, all with cold beer. All the electricity needed has been generated by a combination of the Ampair 100-watt wind generator on her mizzen masthead and a taffrail water turbine.

This was in the days when the three-way masthead light had an incandescent bulb drawing 3 amps. Belowdecks, lighting consisted of low-amperage fluorescent lights, but each still drew 1 amp. Quiet and reliable 300-watt wind generators, affordable LED lights, and efficient 12-volt refrigeration units were still in the future.

Today, with the combination of a 300-watt wind generator when the wind is forward of abeam, backed up by the water-powered generator when the wind is abeam or aft, a boat should expect to be able to produce 200 APD reliably on passage.

A tricolor LED masthead light draws 10 APD, LED lights below deck probably no more than 20 APD, a properly installed and insulated refrigeration system no more than 15 to 20 APD, and a deep freezer the same. Watermakers are available that draw as little as 1 amp per gallon. If the crew is willing to limit water consumption, there should be enough amperage produced to allow limited use of a watermaker, permitting occasional showers.

As soon as the wind goes abeam, the drag of the water turbine is not important, so it’s streamed. The water turbine, depending on which model you’re using, will produce 120-plus APD.

On trade-wind passages, where boats are knocking off 160 or more miles per day, water turbines kick out an absolute minimum of 144 APD, backed up by the wind generator producing 70 to 90 APD, for a total of about 214 to 234 APD when sailing dead downwind. If the wind is on the quarter, the apparent wind will increase, and the total APD may be 250 or more.

My advice is this: Do not buy a wind generator unless the salesman will put you in contact with three people who have had the same model mounted on their boat for at least one full year. This is essential to ascertain if the output of the wind generator matches up with the claims of the sales brochure. Noise level, reliability and after-sales service must also be checked.

Similarly, a water-powered generator should not be bought until you have talked to sailors who have made at least two long ocean passages using the same model.

If the wind generator is not mounted high on a mizzenmast, it must be mounted on a pole tall enough that the tallest member of the crew, going aft for an early-morning stretch, will not have his fingernails clipped by the revolving blades.

In port, the Aquair 100 can be made into a wind generator. The fan is pulled out from below and assembled (blades are numbered so it will stay in balance and not make noise), then hoisted on a halyard with guy lines well above anyone’s head or fingertips. The higher it’s hoisted, the more wind it gets and the more amperage it produces.

Paul and Jenny Davies, the parents of Volvo Ocean Race skipper Sam Davies, have sailed Nanita doublehanded for many years. Nanita is an exact replica of the original Nina, a 63-foot schooner that won the 1928 race to Spain. They have an Aquair water-turbine/wind-generator combination and love it.

Nanita is big and fast enough that they are not worried about the drag of the water turbine going to windward, so on passage they tow the water turbine all the time. At anchor they hoist it in the rigging and use it as a wind generator.

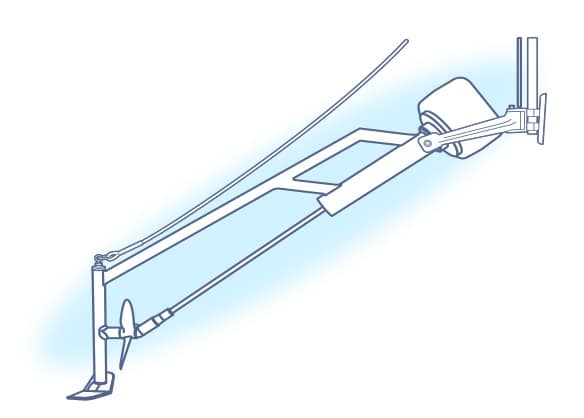

For those who are willing to experiment, almost unlimited amperage is available from a shaft-driven alternator, which uses the boat’s freewheeling propeller to generate electricity.

If you are contemplating a lot of offshore cruising, especially a trade-wind passage to the Caribbean, or heading across the Pacific, you certainly should install a 300-watt wind generator and a water turbine.

When on passage, why tolerate the noise and fumes of running an engine or generator just to charge the batteries, when wind and water can do the same silently with no pollution?

Resources:

Ampair

The company is now owned by Seamap and based in Singapore. At press time, Seamap is manufacturing the hybrid Aquair 100 and has parts available for the Ampair wind generators.

www.seamap.com/products/ampair

Eclectic Energy

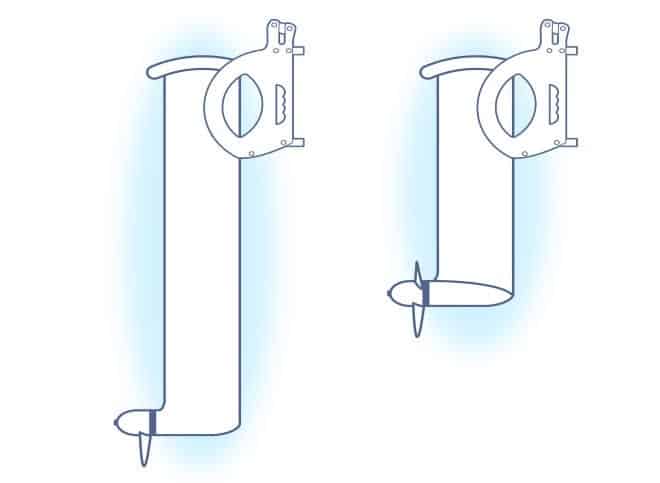

Based in the U.K., Eclectic Energy produces the DuoGen hybrid wind/water generator, the Sail-Gen water generator and the D400 wind generator.

www.duogen.co.uk

Hamilton Ferris

The Ferris WP-200 can be towed behind a sailboat or easily converted to a wind generator in port. The unit has been in production since 1975 and is made in Massachusetts.

www.hamiltonferris.com

KISS

In production for more than 20 years, the popular KISS wind generator is now available from Cruise RO Water & Power.

www.cruiserowaterandpower.com

Primus Windpower

Primus Windpower, located in Colorado, produces the popular Air X wind generator along with the Air Breeze, Air 30, Air 40 and the new Air Silent X.

www.primuswindpower.com

Rutland Windchargers

U.K.-based Marlec produces the range of six-bladed Rutland Windchargers, which includes the 504 and the 914i. In 2016, the company will introduce the 1200, a three-bladed model.

www.marlec.co.uk

Watt & Sea

Watt & Sea is a French company that manufactures “outboard”-style hydrogenerators. There is a version for racing sailboats and a simplified version for cruising sailboats.

www.wattandsea.com

Don Street, lifelong sailor and prolific author, is a passionate supporter of green energy aboard. Thanks to the Cruising Association in the U.K. (www.theca.org.uk) and the editors of their in-house publication, where this article originally appeared.