Much farther and there will be no turning back. We’ll be committed to a narrow slot that is literally between a rock and a hard place. I’m feeling anxious, picking up on the wariness of both Karl and Mary Beth, whose boat this is. Michael, my husband, scouts ahead with binoculars and sees the house we’re to aim toward, but it’s not blue as stated in the guide. Standing on the rail, I can make out a stake hidden by the yellow seaweed. Maybe the one we’re to leave to starboard? Mary Beth suddenly turns Hattie Lee around and heads back out.

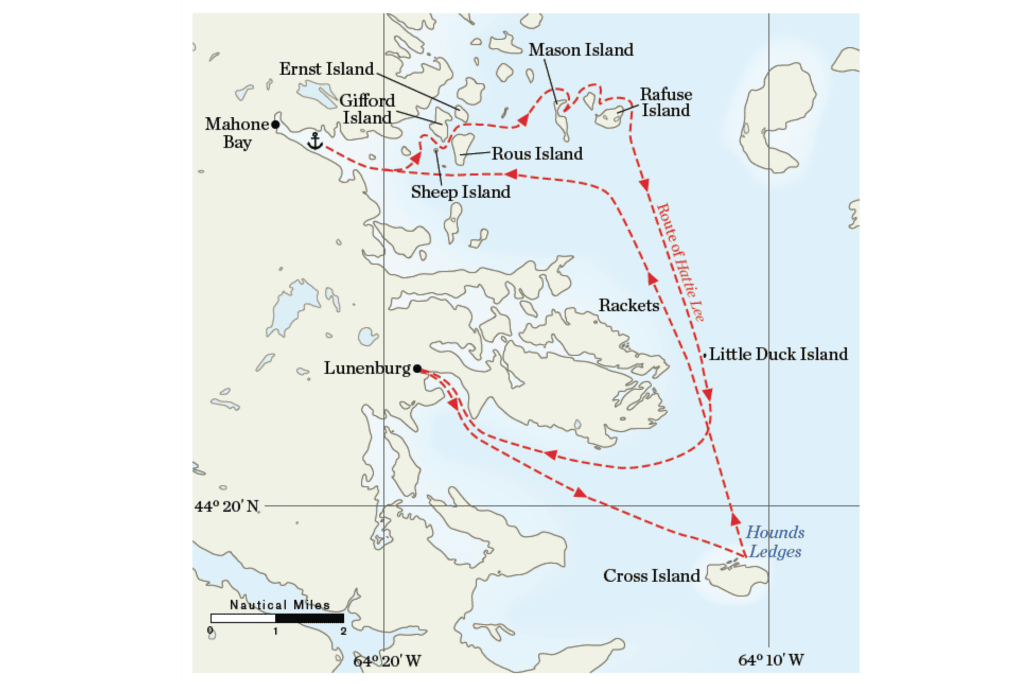

Just two days ago we joined Karl and Mary Beth for a week in Nova Scotia cruising aboard their 36-foot Cape George cutter, Hattie Lee. We met in Lunenburg, where the architecture and civic design are so classic of a planned British colonial settlement that it is designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

We had an uneventful 8-mile passage to Cross Island, where we now spin, debating whether to proceed or chicken out. We move in circles while Karl reviews the cruising guide directions, bearings and landmarks. The whole island is a mere speck in the ocean, about one square mile of wooded rock, with a lighthouse at the east end and a few occasionally occupied fishing shacks at the other. We’d been both lured to and warned away from the island by Peter Loveridge’s Cruising Guide to Nova Scotia. “The entrance is difficult for strangers and extreme care is required,” he warns. But only by succeeding will we have “truly cruised the coast of Nova Scotia.” How could we not try?

Karl nods at Mary Beth, who turns the boat toward the narrow entrance again. Each of us takes a watch, looking under and ahead and to the side. Though moving in slow motion, the boat seems to be going too fast. I realize it is because of the irreversible trajectory — like jumping off the high dive or shoving off from the dock, that sense of commitment to letting go.

As we head into the granite chasm of a harbor, I realize the shoals we passed earlier, the Western Hounds and Hounds Ledges that lay near the island like welcome mats, top-heavy with grey seals, looked deceptively rounded and soft. Nothing is really rounded or soft here. We can only hope that the house we are steering for, gray not blue, is the house we’re supposed to be aimed at. We’ve got a wooden stake to starboard and a house at 270 degrees, so we proceed, on faith, at a snail’s pace into the gut. Each of us is staring over the side and ahead, looking for danger for what feels a long time. When it appears that we are in the right channel, I take a breath. A mooring ball appears straight ahead, but Mary Beth passes it by, continuing to one farther inside. Very quickly we secure to the mooring, looking under the hull at the rock ledges below our 6-foot keel. Except for one suspicious outlier rock, we agree it looks safe.

It’s beautiful. Quiet. Solitary. Our space is filled with spruce trees, granite, grasses, sea, seals and terns. A whisper quiet is punctuated by the occasional swoosh of a roller sliding across the ledges. It’s like this all afternoon as we explore the exposed rock on foot, slithering over the slimy seaweed exposed by the ebb tide. Seals loll about like fat sausages with whiskers. Gannets torpedo down for small fish. Willets, piping plovers, least sandpipers, common terns, a bald eagle and a kingfisher all hunt around us. For nature lovers, this is a feast.

Continuing along the shore, past haphazardly arranged shacks, I realize that these belong to the current generation of fishermen, whose homes are on the mainland. A hundred years ago, their ancestors fished the island full time. Today, there aren’t enough fish left to recreate such a life. With that thought, a mosquito takes a sip of my blood, and I head back to Hattie Lee. As night falls, we sit on deck with our wine, with nary an annoying buzz.

Now that we are at the site of a historically significant fishing village, we get to talking about our visit to the Fisheries Museum in Lunenburg. That’s where I first understood the importance of fishing in Nova Scotia. Boarding a recently retired dragger-fishing vessel, I struck up a conversation with a gentleman who had been captain of the boat for some 30 years. This fact I discovered too late to prevent me from indignantly proclaiming the terrific damage to the sea floor and peripheral creatures wreaked by this style of boat. Tourists, his look said, his eyes expressing both forbearance and a bit of twinkle. I feel the tourist he sees in me.

In the early morning that outlier rock clonks on the hull, letting us know we should move because it won’t. Shortening our mooring chain as well as tying off to a second mooring solves the rocky conflict. The day’s dead calm is forecast to continue, so we feel comfortable heading out in the dinghy for another island exploration.

It’s no easy task dodging the sharp rock ledges in our rubber dink to reach the gravel landing. The tide will be out when we return, so we’ll have a long haul back to the water later. We mull this over as we lift the dinghy above the tide line. The Spanish have an expression for our efforts — vale la pena, or “it’s worth the trouble.” I’m grateful that we all consider exploration — seeking to map new territory in our lives — to be a vital aspect of why we cruise.

An old chart shows a path leading from the bay to the lighthouse at the other end of the island. From the early 1800s to as recently as 1990, this was the route for the keeper of the lighthouse and his family. In fact, the author of our cruising guide, Peter Loveridge, once had the privilege of visiting with the keeper “and his one-eyed dog and three-legged cat.” After some scrambling around, Karl finds the path, which our guidebook suggests is behind the beach “somewhere.” We can’t be sure that this is the right beach or that the path still exists, but it is encouraging to know that now we might be able to reach the lighthouse at the east end of Cross Island. A long walk will help give a perspective of depth beyond the two-dimensional edge of the island we view from the sea.

Our path parallels the beach through fields of aster, downy thistle, grasses and flitting butterflies. Farther inland, stumpy pines huddle around a small freshwater pond. Hiking alone with no signs of civilization enhances our feeling of pioneering discovery. From the pond the path returns to the shore, now along the edge of a cliff. Looking down I can see deep cuts into the rock, striated with the colors of a journey much wilder than our own. Initially deposited off Africa, these rocks were later thrust up against North America by continental drift millions of years ago. Magma flooded the cracks and fissures in a southwest-northeast orientation that made the rocks look like slices of bread. Glaciers came later to knock off the crust, and what was left is what I see here. Clearly I have been looking at the same ancient folds under Hattie Lee, under the dinghy and underfoot.

As we continue on our way, we pass a small inlet called Oil Cut, where I imagine oil was brought ashore to power the original lighthouse beacon 150 years ago. The lighthouse has been rebuilt twice, and is now automated with the help of solar power.The lighthouse keepers’ houses we find are in ruins, gutted of all reusable materials. Walking inside and looking through the empty windows on this clear, sunny day, I imagine myself living on this lofty hill overlooking the Atlantic. I call this feeling the “romance of imagination” — or illusion. You rarely consider the months of isolation, the bad weather or restricted mobility. It’s not so different from the romance of any unknown, sailing included. You have to love the whole package, which, when you think about it, is not so different from life itself.

Letting go of that dream, I walk out to join the gang by the cliffs. We picnic, just the four of us, watching a fishing boat bob in the heavy rollers 60 feet below. The fisheries have taken a beating in Nova Scotia, just like everywhere else. Despite their high original numbers back when the Vikings were hauling in cod, fish are no match for humans and fossil-fueled machines. In the late 1970s, Canada extended its territorial fishing waters to 200 miles to save the industry. Even that was not enough. If they wanted anything at all, fishermen themselves realized, they needed to limit the harvest. Since the lobster season is staggered and generally does not include the cruising season of July to late September, we mariners are relieved of dodging entangling pot lines. I find the fishermen’s discipline in the face of the fisheries’ imminent collapse reassuring, although I’m fairly sure self-regulation is the ideal, not the given.

An hour later we are hauling our dinghy 100 feet to the water. Although the outboard won’t start, our apprehension about a rough return trip proves unfounded. Anxiety must be the dark form of illusion. It’s enough to keep you from doing something you can do, as much as the romantic encourages you to go right ahead with something you may not be prepared to do.

Our last night on Cross Island, mosquitoes swarm with a vengeance — a reminder that one night does not a reality prove. I grab my drink and, with a farewell to the setting half-moon, follow the others below.

The calm weather holds through the next morning, giving us fair visibility and calm seas to get ourselves out of this geologic wrinkle. Steering northerly, we pass forlorn Little Duck Island, a silhouette of skeletal trees bleached with cormorant droppings. We leave the maze of islets called the Rackets to port, and make our way closer to the mouth of Mahone Bay. We anchor in a snug pond formed by three islands — Gifford, Rous and Ernst — and once again, all is silent. The boat shed on Gifford is quiet, and the one other boat in the pond appears to be unoccupied. The only beach we are confident to land at is on Sheep Island, which we passed on our way into the anchorage. Because the currents are running through the channels between the islands, and the distance to Sheep is farther than any of us wants to row, Karl is trying again to get the outboard running. Michael told him yesterday that the only spark plug aboard gave no spark, but Karl bends to the task with diligence, and soon the motor coughs to life. I feel like we should all recite Kipling: “If … you can trust yourself when all men doubt you.” His perseverance is all I can think about for the rest of the day.

Sheep Island is a mere 500 yards long, with an abbreviated sandy hook that completes the island’s shape of a stingray. We pull the dinghy up on the sand, where Michael and I strip for a swim. The water is barely 60 degrees, but it feels comfortable enough. Swimming along the shore, I can see a large boulder that appears to contain hundreds of sea creature fossils. We’re swimming around an island that was once far under the sea, sailing slowly away from Africa. What a tiny bit of earth we experience in our brief lives.

The air temperature hovers at an above-average high in the mid-70s. Shirtsleeves in the day, long sleeves at night and no sign of fog make cruising a joy. We are just plain lucky.

We take a short dinghy ride from the anchorage to a dock on the mainland, where Michael and I opt for the 4-mile hike to the town of Mahone Bay. Because the roads are quiet, it’s a pleasant walk, past houses perched on hills adorned with cultivated lawns on the one side and small seaside cottages on the other. Though nobody waves or stops to offer us a ride, the locals’ good-natured personality appears in the whimsical wooden creatures peeking out of tree trunks.

In Mahone Bay we meet up with Karl and Mary Beth, who have sailed Hattie Lee to a mooring just offshore. Much like tourist towns in Vermont or Cape Cod, Mahone Bay sports funky shops and restaurants. As we sit overlooking the harbor for a very tasty seafood lunch, what impresses me most is the youth and quiet of the clientele. The whole day has been singularly noise-free: no mowers, blowers, music or loud voices around us. The tranquil mood stays with us as we sail around Mahone Bay, enjoying the easterly wind and protected seas blessedly devoid of lobster traps (unlike Maine), then head back to our pondlike anchorage for the night.

With so many islands inside Mahone Bay, we have a choice of protected anchorages with views of forest, beach and expanses of island-dotted ocean. Sunday morning we head for Mason Island with its curved sand beach, about 3 miles to the east. We set sail and are soon joined by cruising and racing sailboats pouring out of Chester Harbour.

When we arrive at Mason, Sunday cruisers have claimed much of the anchorage along the beach. It’s not so much the company of other boats, but the wind, persisting from the east, that makes us consider moving on. In the current wind direction, this is no real harbor at all. There’s no dismissing the lure of the crowd, the X on the chart that clearly states one should anchor here. But after swinging wildly on our hook, we move around to the west side of the island. Though we are the only boat choosing to anchor off this shore, we feel secure in the perfect calm. With all the other boaters on the other side in the conventional anchorage, we have this narrow beach to ourselves. No people, no bathing suits. While Karl and Mary Beth explore the red sand beach, Michael and I enjoy a nice long swim in water almost as clear as the Caribbean.

Though the anchorage is good for the day, none of us wants to dare the night. We’ve had too many emergency moves in the dark to take a chance on wind shifts, so in the late afternoon we up anchor and drift across the mile to Rafuse Island. Here we tuck into a semicircular cove for the night. There’s no competition for anchoring space, but we have trouble finding water shallow enough for dropping the hook without putting ourselves on the beach. Years of gravel mining have turned this basin into a deep quarry with steep sides. Finally, circling around in front of the sandbar connecting Great and Little Rafuse, we find an area that’s about 30 feet deep and anchor. Though the sandy beach looks inviting, the cruising guide informs us that the owner has gone to great lengths to keep people off, despite 150 years of public use. There is a strong suggestion to challenge this stance, but the owner’s beautiful Herreshoff sailing dinghy puts us in a more sympathetic mood, and we remain in the cockpit for sunset.

By all rights we should have endured at least a few fog-shrouded mornings. Apparently the cold Labrador Current and warm Gulf Stream have called a truce, as we’ve been blessed with clear blue skies and warm days the entire week. Our best sail of the trip comes on our last day. A light wind swings to the southwest and we set all four sails, leaving Mahone Bay astern. Breezing past the familiar Rackets and Little Duck, we haul northwest around Fairhaven Peninsula. From this distance, Lunenburg appears and rises uphill from the harbor. Roofs in shades of red and orange and yellow stack up one above the other like a Cubist painting, protectively overlooking the curved shorefront of yachts and fishing vessels. T.S. Eliot wrote, “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” No longer a stranger to the town or the bays, I feel I am coming back into my home port.

Since shipwrecking in the Bahamas 40 years ago, Ida Little and Michael Walsh continue cruising shoal-draft craft from Nova Scotia to the Bahamas. They are co-authors of Beachcruising and Coastal Camping, available from Amazon.