|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| Billy Black|

| |

|

|

| |

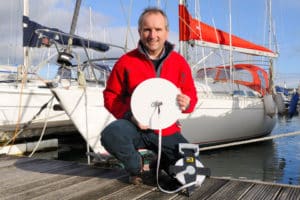

| Past and future run side-by-side as the older-style Bombardier-built two-stroke 15-horsepower engine (left) and the quieter but heavier four-stroke Johnson 15 (center), made by Suzuki, churn up Long I* * *|

| |

|

|

| How quickly the times can change. Five years ago, we looked at 9.9-horsepower outboards as possible propulsion for pocket cruisers. This spring, we tested the latest crop of 15-horsepower outboards, regarding them as potential dinghy engines. While many part-time cruisers, like me, are still quite happy rowing to shore or puttering around with a 3-horsepower engine, a growing number of long-termers are choosing double-digit horsepower to push a 10-foot-plus RIB thats filled to the brim with people and gear. A 15-horsepower engine is about the smallest outboard that will get a fully loaded four-person RIB up on a plane, so thats where we drew the line for our 2003 test. The drawback? These engines weigh somewhere between 74 and 117 pounds–hardly portable. But for RIB owners who want some serious oomph, this is the weight range they have to live with. Going down a notch to a 9.9 wont make a weight difference, since most brands use the same basic block for their 9.9- and 15-horsepower engines (Honda, with a 92-pound 9.9 and a 107-pound 15, is the only exception). If less weight is more important than more thrust, you have to drop down to 8 horsepower or less to find a selection of engines under 60 pounds, although Tohatsu makes a 9.8 that weighs 58 pounds.

After three days of muscling the big 15s into place, it became clear–achingly so–that if you want 15 ponies pushing your tender, you dont want to be taking the engine on and off the transom too often, especially if its a four-stroke version, which will be bigger and heavier. Todays cleaner-burning four-strokes are lighter and more compact than earlier versions, but the two-stroke 15s are still featherweights by comparison and, thanks to recent advances, more fuel efficient and quieter than two-strokes of just five years ago. So if your hearts set on a quiet, environmentally friendly four-stroke, you might consider looking at these manufacturers offerings in the 8-horsepower-and-under range. With more power, also consider that davits, a dedicated engine hoist, and substantial stern-rail brackets become necessities for most mortals.

Although no clear winner emerged from our testing, we found features we liked in every engine. In a perfect world, all these positive attributes would be combined into a quiet little four-stroke that tipped the scales at a dainty 70 pounds or less. Dreaming? Maybe so, but as environmental legislation both in the United States and abroad continues to push toward four-stroke technology, and engineers are consequently forced to whittle away at the horsepower-to-weight ratio, our ideal engine might not be so far off.

The Competitors

Our test featured 2003 models from the major manufacturers that offer a 15-horsepower engine in the United States: Honda, Johnson, Mercury, Suzuki, Tohatsu, and Yamaha. We looked at the four-stroke 15s from each and at the two-stroke 15s from Johnson, Mercury, and Yamaha. (Suzuki and Tohatsu are phasing out two-strokes in this size, and Honda has long focused only on four-stroke engines.) Two brands that appeared in our 1997 test dropped off the roster: Brunswick, the parent company of Mercury and Mariner outboards, now markets its Mariner outboards only abroad; Evinrude (like Johnson, a former Outboard Motor Corporation line that’s owned by Bombardier) has discontinued its small-engine line. We didn’t include the Nissan 15 because Nissan engines are the same machines as Tohatsus, with different paint and cowling decals.

The Test

We divided the test into two parts. Off the water, we weighed the engines “wet” (which includes a small amount of fuel in the system and, on four-stroke engines, oil in the crankcase). The weights we recorded were 3 to 7 pounds more than the manufacturers’ published dry weights, which in some cases didn’t include the weight of the propeller. We looked at how easy it was to carry the engines and to take them on and off the transom of our test boat, a 10-foot Avon 310 RIB. We evaluated the tilt/ trim, throttle, and gear-shift mechanisms. We considered each engine’s serviceability, including gauging how easy it was to flush it with fresh water and, in the case of the four-strokes, to change the oil and the oil filters.

Our on-the-water testing took place in Long Island Sound in about 7 knots of wind with a very slight chop. First, we used a decibel meter to determine actual noise levels at idle, at harbor-cruising speed, and on a plane. For our fuel-economy tests, we timed exactly how long we could run on 4 ounces of fuel at an average speed of 5 knots, the limit in most harbors.

The Results

Size and weight: The size of the four-strokes and the lack of good handholds (only the Honda had a grip that seemed useful) reinforced my impression that the designers didn’t intend these engines to be portable. The unwieldy nature of these engines is a major drawback for offshore cruisers, who may want to store their outboard on a stern-rail bracket. And should you have to lay a four-stroke engine on its side, you must make sure the correct side is up; otherwise, oil will drain into the cylinders, making the engine difficult to start again.

On average, the four-strokes were 29 percent, or about 32 pounds, heavier than their two-stroke counterparts. The 100-pound Suzuki stood out as the lightest four-stroke. The 117-pound Tohatsu was the heaviest of the group. The 74-pound Johnson, the lightest in the two-stroke category, was a relief after a morning of manhandling the big boys.

Fuel efficiency: In 1997, we found that the four-strokes were 45 percent more fuel efficient than the two-strokes. Using essentially the same test in our 2003 comparison, I was stunned to find that on average, the two-strokes were 17 percent more fuel efficient than the four-strokes. With more testing at varying speeds (instead of at just one speed, 5 knots), Im sure that the four-strokes will have a better average fuel economy than the two-strokes; our test just happened to find an inefficient rpm for the four-strokes. Nevertheless, its obvious that the fuel efficiency of two-stroke outboards has significantly improved since 1997. Yamaha proved to be the most fuel-efficient two-stroke, while the Tohatsu turned out to be the thriftiest four-stroke, followed closely by the Honda. In general, the difference in fuel efficiency among all engines was relatively small and inconsequential.

Emissions: All the engines are rated with one, two, or three stars according to California Air Resources Board (CARB) standards, some of the strictest in the world; the more stars, the cleaner the emissions. Interestingly, the two most fuel-efficient engines, the Tohatsu and the Honda, were the only ones that earned the superior, three-star rating; these engines meet the new ultra-low CARB standards for 2008, with emissions that are 65 percent below the 2006 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards. All of the other engines had two-star CARB ratings (see sidebar, “CARB Stars Deciphered”)

Noise pollution: Quietness is one of the main reasons people are turning to four-stroke outboards today. Normal conversation will typically measure about 65 decibels; 90 decibels is the measurement at which unsafe levels of noise begin, and thunder averages around 110 decibels. In our 1997 full-throttle test, at least one of the two-stroke engines hit 100 decibels, an unsafe level for prolonged exposure. This year, we compared noise emission at three speeds: at idle, at 5 knots, and on a steady plane. Among the four-strokes, the Honda came in with the quietest average, followed closely by the Suzuki. In many cases, the difference was less than 2 decibels, almost imperceptible to our ears. The loudest four-stroke at planing speed, the Mercury, registered 94 decibels, only slightly louder than the others, which generated 90 to 92 decibels. Conversely, Mercury had the quietest two-stroke. The two-strokes were 3 to 7 decibels louder than the four-stroke engines at planing speeds and 5 to 6 decibels noisier at 5 knots, a noticeable increase in both instances. The loudest of the bunch was the Johnson two-stroke, which hit 99 decibels on a plane.

Engine Controls

Because dinghies are often operated in extremely shallow water and are frequently beached, the ability to easily trim, or tilt up, a dinghy engine to get it up and out of the way is particularly important. All of the tilt mechanisms worked well once we figured out the secret formula peculiar to each, but these mechanisms aren’t as intuitive as they could be. The clear winners here were the Suzuki and the Johnson (made by Suzuki, the Johnson is essentially the same engine with a white cover and some subtle differences). To tilt these engines, you simply push a button at the front of the mounting bracket, then pull on the back of the cowling.

Proper trim is particularly important on a small boat. An engine trimmed too far up will cause the boats bow to rise and make it difficult or impossible to bring it up on plane. An engine trimmed too far down will cause the bow to plow, creating a wet ride and making steering difficult. Generally speaking, the more trim adjustments the better, and our selection ranged from three positions for the Mercury two-stroke to six on the Tohatsu four-stroke.

Ive always been a fan of separate throttle and shift controls on small outboard engines. When by accident we flood the engine with fuel, this arrangement allows us to rev up to clear fouled spark plugs without putting the engine in gear. Back in the 1980s, nearly every manufacturer tried a combined throttle/shift twist grip, but in todays group, only the Mercury two-stroke still used this system. Id be happy to see it go.

Steering friction will control the force required to turn the engine. More friction allows hands-free operation in open water; a looser setting best suits maneuvering in tight quarters. Ideally, steering friction should be easy to adjust, and the simple lever mechanism found on the front of the Honda, Mercury, Tohatsu, and Yamaha four-stroke engines as well as on the Merc two-stroke does the trick. Three of the engines required wrenches to adjust friction, and the Johnson two-strokes age-old set-screw design isnt much better.

Maintenance Details

Corrosive salt deposits can ultimately restrict water flow through an outboard’s cooling system, so any setup that makes it easier to flush the cooling system with freshwater will prolong the engine’s life. Historically, flushing required fitting an adapter “muff” over the cooling passages and connecting this adapter to a hose. Although all of the two-stroke engines still require this procedure, the four-strokes, except the Honda, came with improved systems that didn’t require muffs. The Yamaha four-stroke had the best setup, with a threaded fitting on the housing that connects to an ordinary garden hose.

Four-stroke engines require oil and filter changes, and some engines made this task easier to perform than others. Mercury and Tohatsu have convenient spin-on oil filters, just like modern automotive engines. The Honda, Johnson, Suzuki, and Yamaha use harder-to-service cartridge filters; changing this type involves unbolting a cover on the engine block to remove the cartridge element.

Any cruising sailor looking for a new engine should take a good look at the service network behind it. The availability and price of spare parts and the duration of the warranty are significant considerations. All of the engines we looked at offered anywhere from one- to three-year warranties, but in many cases, these warranties arent transferable outside of the United States. When you study the table on pages 00 and 00, remember that the best initial price may not be your best deal over the long term. If you cant easily find parts or get service in your area, the expense and delay of getting your engine running again will quickly erase any memory of the money you saved.

Ed Sherman is Cruising Worlds electronics editor and the author of Outboard Engines: Maintenance, Troubleshooting, and Repair (International Marine, 207-236- 4837, www.inter nationalmarine.com)

15-horsepower Two-Stroke Engines

Yamaha 15

At a hefty 86 pounds, the Yamaha was the heaviest of the two-strokes by a considerable margin. It did, however, show noticeably better fuel economy than either the Johnson or the Mercury models. The engine fell right in the middle of the noise range both while idling and at planing speeds. In terms of starting, acceleration, and overall handling, the engine performed flawlessly. My only wish is that the folks at Yamaha could figure out a way to trim 10 pounds off this engine and add a steering-friction mechanism like the lever that worked so well on the Mercury. One curious note is that the Yamaha has a slightly smaller, 2 1/4-inch maximum opening on the yoke for its mounting bracket. While this may not matter on some boats, this was the only engine in our group that didn’t fit on the popular Avon 310 or on the West Marine 310 by Avon, which have transoms that are 2 1/2 inches thick. Some minor transom modifications would fix this, but even a tight squeeze here can be a real pain when trying to fit the yoke over a transom.

Mercury 15

The Merc 15 was the quietest of the two-strokes we compared, and at 76 pounds, it wasn’t noticeably heavier than the Johnson. I particularly liked the lever at the engine front, which made it easy to adjust steering friction. Although it took some fiddling for us to figure out the tilt mechanism, Mercury’s simple pull-knob release was fine for getting the engine up when beaching the boat. As a father, I’m a little concerned that it’s too easy to bypass the toggle that Mercury uses for an automatic shut-off switch, to which you can attach a lanyard that the driver wears. Although not much harder to bypass, the slotted-button-and-key system that the other engines use makes more sense to me. Mercury has a huge dealer presence, but the engine comes with only a one-year warranty, versus the two-year coverage that its competitors offer. As with the Johnson, I think this engine has fallen off of the design-development radar screen. Brunswick seems to be throwing more effort into the larger, more profitable engines.

Johnson 15

The two-stroke Johnson doesnt appear to have changed much from its earlier iterations. Aside from a slightly redesigned engine-cowl cover, the engine seemed quite familiar during our test. The Johnson was the lightest of the two-strokes, but it was also one of the noisiest. At planing speeds, the engine emitted 99 decibels of noise, 3 decibels more than the other engines in our group. It also finished last in our fuel-economy test. For friction adjustment, Johnson employs the same screw-adjustment mechanism on the engine-pivot shaft that its used for years. Overall, it seems Bombardier hasnt invested much in this particular engine in terms of design improvements; it has the look and feel of engines from a decade ago. It does, however, come with a two-year warranty, which puts it on a par with Yamaha and gives it a warranty jump over Mercury, at only one year. In a nutshell, if youre looking for innovation, this engine has little to offer. But if youre looking for light, proven design with a huge global presence, this engine is right up your alley.

15-Horsepower Four-Stroke Engines

Tohatsu 15

The Tohatsu 15-horsepower engine came out at or near the top in several categories. It tied with Honda for the best emission rating, three stars. It just edged out the Honda in our fuel-consumption test, and it came out less expensive than every other engine except the Mercury. On the downside, at 117 pounds, it was also the heaviest engine in the bunch. Otherwise, it works and looks just like its Mercury brother.

Whats happening at Tohatsu is probably a good indicator of what to expect in the four-stroke arena. In the past few years, Tohatsu has nearly doubled production at its manufacturing plant in Nagayo, Japan, where it can produce more than 130,000 outboards a year. Its 2004 lineup, scheduled to be unveiled this autumn, concentrates on shedding excess weight. One engine that looks promising to us is the new 9.8-horsepower four-stroke, which weighs just a tad over 81 pounds, a good deal lighter than any other engine in that category and only 6 pounds more than some of the two-strokes we tested.

Yamaha 15

This 15-horsepower engine has all of the features I like and more. Though not the lightest in this group, the Yamaha ran noticeably smooth and quiet at harbor speed. One of its best features is the hose-adapter arrangement. Located up on the side of the engine case, where it’s accessible, it allows you easily to attach a garden hose for a quick freshwater flush. This is one of the simplest and best things you can do to help reduce maintenance woes on an outboard engine used in salt water. The Yamaha’s four trim-adjustment points provide adequate trim options, though fewer than any other engine in this group. Yamaha’s strong point is, again, its dealer and service network. With 2,400 dealers in the United States and Canada and tens of thousands dealers worldwide in 180 different countries, Yamaha is a name with universal recognition. In general, Yamaha engines have a reputation for being reliable. The engine is backed by an excellent network of well-trained technicians, and Yamaha’s willingness to offer a two-year warranty on this engine indicates the great faith it has in its product.

Honda 15

Nobody has more experience than the folks at Honda when it comes to four-stroke outboard technology. The company has been making four-strokes for nearly 40 years, and the refinement of its product line shows it. With a wide presence worldwide and 900 dealers in North America alone, getting support shouldn’t be a concern.

One of only two engines in our roundup with a three-star rating from the California Air Resources Board (CARB), the Honda BF 15 beat out all the two-star engines in our fuel-economy test. Honda uses a decompression system to make its engines easy to pull start. Our engine was quick and easy to start, even after we ran all the fuel out of the system as part of our test. Honda also touts its higher displacement, high torque, and greater thrust. Interestingly, it was the only engine in our group with a four-bladed propeller, which, in general, delivers more thrust. Given its built-in 12-amp charging system (the highest output in our group), I can definitely see this engine serving double duty for some users: on the dinghy and as primary propulsion on a smaller weekend cruiser.

Johnson 15

A Suzuki in a white cowling, this engine bears little resemblance to the familiar Johnsons formerly made by Outboard Motor Corporation (OMC). When Bombardier acquired Evinrude and Johnson from OMC in 2001, part of its revitalization plan involved turning to outside suppliers for the new Johnson line and narrowing this line to engines of 70 horsepower and less. Suzuki, which is focusing on four-stoke technology for its small engines, was a logical choice for a 15-horsepower four-stroke. We were very impressed with this engine’s compact form. Our electric/manual-start engine was slightly heavier than the straight manual version we’d want for our tender, but it was still one of the lightest in the group. The one-button tilt mechanism was our favorite, and the engine controls were easy to use and well placed. At press time, Bombardier was reviewing bids for the purchase of its recreational division, which includes Evinrude and Johnson. The sale isn’t expected to disrupt Johnson’s wide dealer and service network in the United States, a bonus with this particular engine.

Mercury 15

Mercury’s parent company, U.S. marine manufacturing giant Brunswick, is a big investor in Tohatsu, so it comes as no surprise that the Mercury 15-horsepower four-stroke is made by Tohatsu. Like Suzuki, Tohatsu is also shifting almost exclusively to four-strokes in the smaller engine size, making it a capable partner for filling this niche. Aside from Mercury’s famous black paint, we could see some minor differences between the Tohatsu and the Merc. I noticed that the Mercury has five trim-adjustment positions; the Tohatsu has six. Another odd difference is that the Mercury has only a two-star emission rating, whereas the Tohatsu version received three stars. Our tests showed no noticeable performance difference between the two engines. We liked the Merc’s automatic-enrichment device, which enables easy starting without fiddling with a choke button. Mercury has a huge dealer presence in North America, and Tohatsu, which also supplies the Nissan brand, has a wide presence worldwide, so the global service and parts network for this engine is comprehensive.

Suzuki 15

We liked all of the same things about the Suzuki that we liked about its twin, the Johnson. The Suzuki was the lightest engine in this group and one of the quietest. Its noise at idle speed was right down there with the Honda at 65 decibels, the same decibel range as normal conversation. It was smooth running and easy to operate. One missing feature that I would have really appreciated was the lever-type steering-friction adjustment found on all of the other engines in this group. The only significant difference between the Suzuki and the Johnson four-strokes is the dealer density. Currently, Suzuki has about 525 dealerships in the United States, including Hawaii and Alaska. By comparison, Johnson has about 1,572 full-line dealerships. Suzuki has worked hard to expand its network in the past 10 years, but in certain areas of the country, you may still find it difficult to locate an authorized service center. If your area has a convenient dealer, than this engine is definitely worth a close look.