A Pearl of the Pacific

Having spent nearly two weeks in the Pacific Ocean’s Line Islands, just north of the equator, and with some unsettled weather approaching from the north, my fiancée, Gayle Suhich, and I departed on a less than ideal day bound for the South Pacific. Our initial destination aboard our Flying Dutchman 50, Small World II, was somewhat open-ended. We were of half a mind to stop at Penrhyn Atoll in the Cook Islands, nearly 800 nautical miles southward. But we were equally attracted to the notion of heading straight for American Samoa; we could address some business there and then move on to Tonga while it was still early in the season.

Our first night out was full of nasty squalls and heavy rain, and we fell off toward Samoa. However, as each weather cell moved through, our windvane steered us farther east than we had intended. By dawn, with clearing skies, we realized we were only 30 miles west of the rhumb line for Penrhyn. If we just hardened up a bit more and made some more easting, we could possibly lay it on one tack. Finally, a review of the morning’s satellite pictures and weatherfaxes revealed that the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ) — the Southern Hemisphere’s most expansive, persistent rain band — remained fairly well entrenched over Samoa, meaning our passage there would likely have a rough finish with lots more unsettled weather. So we sheeted home the sails and committed to the easterly option.

We were bound for Penrhyn, the largest and most remote atoll among the 15 islands that comprise the Cook chain.

At 0700 we spoke on the SSB radio with some friends who’d planned on sailing to Christmas Island and then on to Bora Bora. But with weather similar to ours, they were abandoning their quest for Christmas and seriously considering a visit to Penrhyn instead. As chance would have it, two days later we spotted them on the horizon ahead; we ended up sailing more or less within VHF-radio range the next four days as we made our way, pinching as much as possible, south toward Penrhyn.

The captain of the convict ship Lady Penrhyn named the atoll. He discovered it for the Western world on Aug. 8, 1788, en route to British Columbia for a load of lumber after discharging a cargo of female convicts in Australia’s Botany Bay.

Although Polynesians resided in most of the Southern Cook Islands as early as A.D. 800, records indicate that remote Penrhyn, called Tongareva by the Cook Islanders, was not settled until the 13th century. Missionaries arrived in the early 1800s, and by midcentury the place was frequented by the so-called Blackbirders, the notorious Chilean slave traders who called it “the island of the four Evangelists.” With the assistance of three greedy missionaries, in 1862 and 1863 a series of raids by these illegal traders removed some three-quarters of the population from Tongareva and nearby Manihiki; they were transported to South America to work the mines, and few ever returned. Finally, in 1888 the Cook Islands became a British protectorate, and in 1901 they were turned over to New Zealand. The Cook Islands attained full independence in 1963, though they maintain strong legal ties with New Zealand.

In the early morning of the passage’s seventh day, we saw land on the port bow. Atolls are always such an amazing sight when coming in from the sea. As the sun rises higher, the turquoise of the lagoon begins to reflect off the clouds; oftentimes, before you actually see an atoll, this reflection is visible from far away. But it was still early and, aside from the smudge of trees on the horizon, the only other signs of land were the thousands of birds flying about. Approaching the island, a pod of dolphins escorted us almost all the way up to the pass; one of them had us laughing as it did barrel rolls under our bow wave, rolling over and over again. You could almost see the glee on its face.

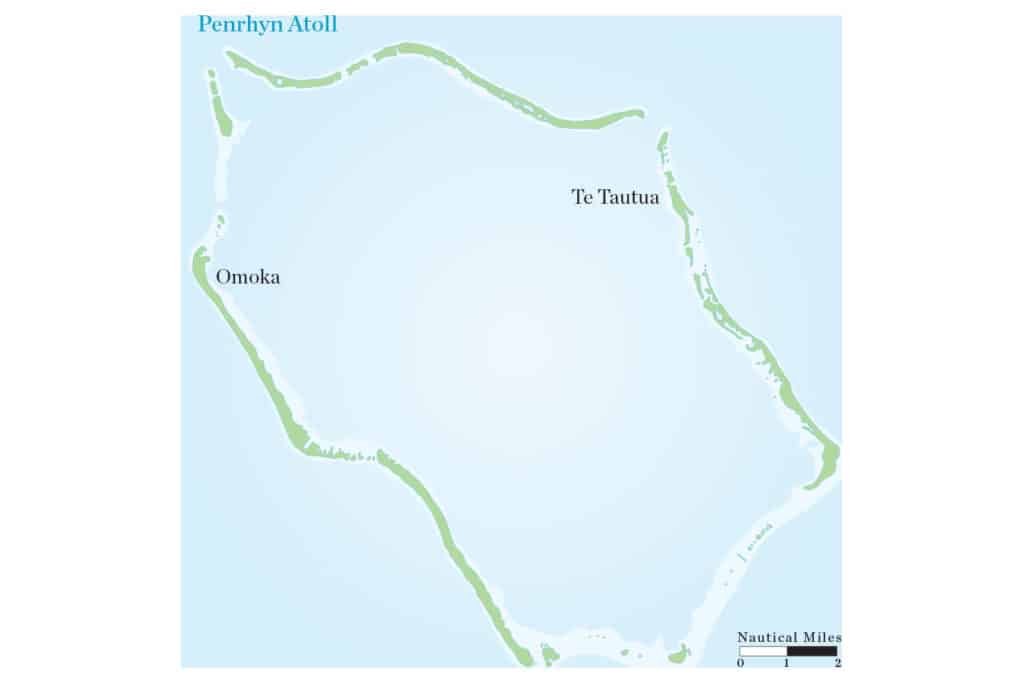

As we waited for the sun to rise a bit higher and for slack water to arrive, our good friends on Ruby Slippers, a Stevens 47 with which we’d left the Line Islands, joined us in Penrhyn’s lee. By 0930 we were both approaching the pass. Like most atoll passes, Penrhyn’s are narrow and have a strong outgoing current with a very brief slack-water period. We weren’t patient enough to wait for it and ended up powering into a 2-knot outgoing flow. However, the pass was easy and straightforward, and only after we turned south toward the small village of Omoka did the tricky navigation begin.

Myriad coral reefs dotted the route to town. Some had stakes marking them with arrows, although it was unclear whether they pointed toward good water or reefs. It seemed like they were aiming toward danger, so we weaved our way through this coral maze until just off the village, searching for a place to anchor. Lots of shallow reefs, a very uneven bottom and a 15- to 18-knot wind coming across the large lagoon made finding a good spot tricky.

I had noted on the Noonsite website a set of coordinates that promised a patch of clear sand, and which I’d also provided to our friends on Ruby Slippers. They were having engine problems and had rigged a tow line that we’d been prepared to take coming through the pass if their engine failed. But they made it through unscathed and anchored according to the website’s recommendation in what seemed to be the only area off the village clear of coral. We were left with a much less desirable spot.

Checking in, however, was easy. Once our hook was set, a man launched a heavy aluminum skiff and made his way out to us. We quickly rigged fenders and watched with trepidation as he came alongside, but he deftly stepped aboard, secured the painter and gave his heavy boat a good shove so it trailed behind Small World with no problems. His name was Ru, and he introduced himself as the island’s customs and immigrations man. Those formalities were completed swiftly, and if the health officer had not been tardy, we would have left that sketchy anchorage and made our way across the big lagoon before sundown. No such luck. We ended up spending an uncomfortable night pitching in the wind and waves a short distance from a foul, coral-strewn shore.

After some difficult maneuvering, Gayle and I managed to raise our anchor the following morning, and by 1030 were on our way across the white-capped lagoon toward Te Tautua, 7 miles away. What a difference this little village was. We found a spot of clear sand in 18 feet of water off the village proper, with the motu providing a perfect lee for us to sit quietly at anchor for the first time in weeks. Our lone neighbor was a French catamaran that had arrived a few days prior to us and was heading back to French Polynesia in a few days.

Penrhyn Atoll is off the regular cruising routes. In 2013, the year before our visit, only 14 boats called there. We were only the fifth boat of 2014, and as soon as we went ashore, we were instant celebrities. A small group of shy but curious children crowded around us with big eyes and genuine smiles. The few adults we met greeted us warmly, and within a short time we were introduced to a family that virtually adopted us for the remainder of our visit. Rio and Kula lived in a tidy, bright blue house with a concrete seawall, and were busy at a large picnic table shucking oysters for food — and for pearls! The whole family helped, including their quiet 5-year-old daughter, Tianna, who adeptly opened the oysters with the best of the adults. Meanwhile, their teenage daughter, Lilly, served us cookies and Tang. After the pleasant visit, we excused ourselves for a look around the village.

Our first impression was how clean it was, with not a single dog or pig wandering the streets. We later learned that it was forbidden to let these animals run free. There were also virtually no flies or mosquitoes, a testament to the good housekeeping exhibited by these friendly, gentle islanders. We were invited to the church service the next day, and afterward were treated to a big lunch at the minister’s house, where we enjoyed fine conversation until early afternoon, when the next service was due to begin. These villagers attended three services each Sunday, and no work — or play — was allowed on the Sabbath.

The next day we took a long walk on the main motu and found a lagoon that appeared to be the quintessential tropical paradise. Gayle was shelling all along the way and found huge purple sea-urchin spines and several shells she had never seen before. On our return to the boat, we heard from the locals that Ruby Slippers, which had stayed anchored on the other side of the lagoon to attend the church services there, was on its way over. By midafternoon they too arrived, and there were now three boats at Te Tautua village. A virtual flotilla!

Over the next several days we extensively explored some of the adjacent motus and passes by dinghy. There are actually three navigable deep-water passes into Penrhyn’s lagoon, and several small-boat or canoe passes as well. With all this clean ocean water pouring in over the reef, the interior of the lagoon, with depths in some places reaching 160 feet, contrasted vividly with the colorful, large coral nodes brushing the surface in other spots.

Navigation here, especially after dark, requires extreme caution, most notably for the small power vessels that regularly transit from Omoka to Te Tautua at all hours of the day and night. But thanks to the efforts of our island host, Rio, there is a buoyed channel across the entire lagoon, with bright blue floats marking its southern edge and black stakes lining the northern side. Knowing this, we were much more comfortable coming across in less than perfect light. Still, a lot of care is required to avoid the many coral patches off the village of Omoka until you learn how to read the maze of stakes on that side of the lagoon. If check-in were possible on the very well-protected Te Tautua side of the lagoon, a lot of the stress and anxiety in visiting Penrhyn would be eliminated.

With a population of less than 250, Penrhyn is truly a remote and unaffected place to see the authentic Cook Islands way of life. Still, times have changed here. Thanks to an enterprising New Zealander in the village of Omoka, who runs the only service station, grocery and general store, there is now also wireless, high-speed Internet. With a repeater in Te Tautua, we were able to make Skype calls, surf the Net and enjoy fast downloads at “first world” speeds from our boat. Amazing. Meanwhile, the kids all watch the latest movies and the adults are all up on world events. Many of the older children are educated in distant Rarotonga or New Zealand, and a few of the more outgoing kids spoke with clear Kiwi accents. Yet in church, the majority of the service was conducted in the Maori language, which is the native tongue of the Cook Islanders.

One day blended into the next, and time passed too quickly. Near the end of our stay, a contingent of New Zealand engineers arrived by private plane and visited Te Tautua to make plans for a large solar array that will service both villages and allow residents to shift from diesel power to solar. The villagers were quite proud of this development, which reflects on the “waste not, want not” attitude we observed in life ashore.

Having noted all the good reasons to visit Penrhyn Atoll, there were some troubling aspects. For instance, because of the extremely lucrative pearl gathering we witnessed, there seemed to be little interest in fishing, farming or local industry. The oysters being brought in by the bushel were, for the most part, very small. Overharvesting may have been the culprit; if these oysters were allowed to mature a bit longer, the resulting pearls might have been larger and more valuable.

Apparently, an Iraqi man has become the sole buyer for the very rare golden Penrhyn pearls, which fetch some of the world’s highest pearl prices due to their unique color and because they are not farmed, but caught in the wild. It seemed that virtually every adult was involved in pearl harvesting or collecting, and they were very reluctant to part with their pearls, which had been promised to the buyer, who was due to arrive in a few more months. We were, however, given a few small pearls as gifts; their color and luster were second to none. Still, an economy based on only one product or resource seemed tenuous at best.

After nearly two weeks, a good weather window opened for heading south to Suwarrow Atoll and so, with great reluctance, we sailed away from Penrhyn. Watching this nearly perfect slice of paradise, and our many new friends, fade into the horizon was saddening. The world is a changing place, but I believe that these hardy, enterprising Cook Islanders will maintain their wonderful homeland and that their lifestyle will endure.

If on your transpacific wanderings you can justify a detour to see one of the least-visited anchorages in the South Seas, one that offers good shelter and protection in normal trade-wind conditions, make the effort to visit Penrhyn. Like us, you’ll be welcomed as family.

Todd Duff and Gayle Suhich are crossing the Pacific aboard their 50-footer, Small World II. This is part of their ongoing series on remote Pacific destinations.