I held my breath as I pulled up the sock to unfurl our spinnaker in Haro Strait. Of the five headsails we’d brought aboard our Santa Cruz 27, this enormous black parachute was the only one I hadn’t bonded with before we’d cast off dock lines in Victoria, British Columbia. We were 50 miles into the 750-mile Race to Alaska—a somewhat insane wilderness adventure where 30-odd teams pedal, paddle and sail a hodgepodge of random crafts from Port Townsend, Washington, to Ketchikan, Alaska—and I was about to learn how to fly a kite for the first time.

Sure, I’ve been aboard other sailboats a handful of times when spinnakers were flown. It always involved male captains wanting to go faster around buoys in big winds; zero discussion of how we would raise, douse or jibe the giant sail; and terrifying near-disasters that elicited lots of confused yelling. So I’d learned only to fear spinnakers, not fly them.

I hoped that this time would be different. The wind was a measly 5 knots, barely filling our genoa. We had a destination that was still days away. And we were a crew of three mid-40s women who were cautious, conscientious, and considerate of one another’s fears.

Our team, Sail Like A Mother, almost didn’t bring any of the spinnakers that came with the boat because none of us had much experience flying them. But we knew we’d likely need at least one in our quiver to navigate the fickle winds of the Inside Passage—especially if we wanted to finish the race before the “Grim Sweeper” tapped us out.

We decided to bring the asymmetric spinnaker, but only after we attached a sock to douse it quickly. We also made sure at least one crewmember, Melissa Roberts, practiced rigging and sailing it in Bellingham Bay prior to the race.

Melissa let out a whoop from the cockpit as the beautiful black sail snapped taut and Wild Card surged forward: “I knew we could do it! I’m so proud of us!” She played out the working sheet and told me to “just steer to fill the sail when it luffs.” Katie Gaut, our team captain, took photos to memorialize the moment.

I stood with the tiller between my legs to feel our course rather than overthink it. It was lovely and sunny, humpbacks were spouting on the horizon, and we were cruising along at the same speed as the wind. After a half-hour, I decided that the spinnaker was my new favorite sail.

That is, until we had to jibe. In the middle of a shipping lane. While three other Race to Alaska teams were watching.

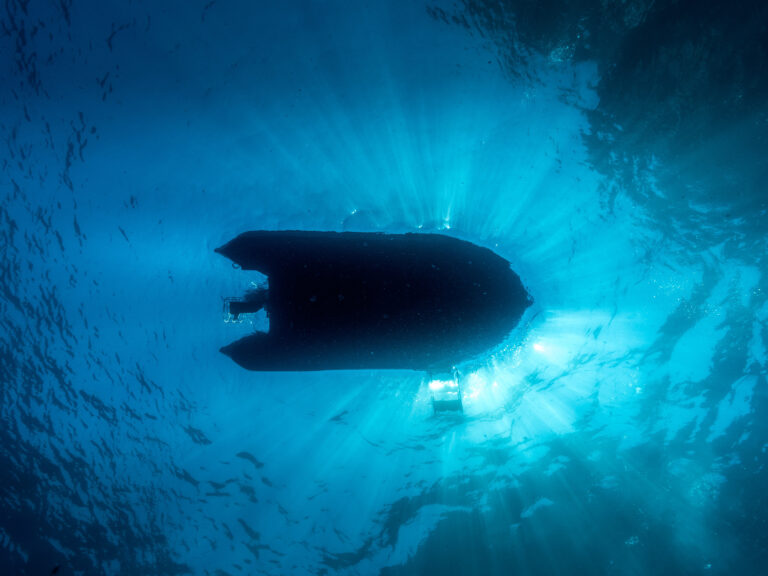

We promptly lost the lazy sheet under the keel, along with our pride. After a few (quietly) yelled questions, I retrieved the sodden rope while Katie took the tiller. This time, we put a stopper knot in it. Then we kept puttering north at jogging speed.

That is, until it got gusty at sunset, and we got nervous and doused it. Which meant the wind promptly died, of course. We gave up on sails and took turns pedaling the bike instead (it’s a contraption attached to our stern that turned an airplane propeller and moved us at 2 knots). Around 1 a.m., we finally made it to Tumbo Island, British Columbia, dropped anchor, crammed ourselves into our coffin berths in the damp cabin, and got four glorious hours of sleep.

Then we rinsed and repeated for 10 more days.

You might be thinking that the Race to Alaska sounds like your personal version of hell. It’s actually hell intermixed with pockets of pure heaven.

Unlike other races that are fraught with complex regulations, the Race to Alaska—or R2AK—is purposefully simple. There are no motors. No outside support. The Northwest Maritime Center first hatched the race in 2015 with this well-thought-out plan: “We’re going to nail $10,000 to a tree, blow a horn, and whoever gets there first, gets it,” says Jesse Wiegel, the center’s race boss.

Second prize? A set of steak knives. This tongue-in-cheek reward, Wiegel says, drives home the point that people choose to compete in this maritime endurance event for plenty of reasons that are more valuable than cash. Or cutlery.

For me, those reasons were threefold. I wanted to prove to myself that I could sail offshore without my husband, who had recently decided that he wanted a break from boats. I wanted to inject some adrenaline into my domestic life, and to show my two young kids that their mother does (way) more than their dishes and laundry. I wanted to become part of the inspiring, adventure-prioritizing, 800-person-strong R2AK community.

Oh, and I wanted to see a lot of whales.

Even though the coveted steak knives would look lovely beside my set from Goodwill, our team had no desire to win them. Our goal was simply to finish the race in one piece, hopefully still friends at the end, and to suffer as cheerfully as possible along the route.

Navigating the mind-bending logistics to get to the starting line was the hardest part. Once our threesome decided to enter, 10 months prior to the race, we began calling and texting one another approximately 128 times per day to iron out details: What boat should we buy? How do we get said boat back from Ketchikan after the race? What will we eat for five to 25 days at sea without a kitchen or refrigeration? Where will we pee without a head? How much drinking water should we bring, and where will we store it? How will we keep our sleeping bags, socks, gloves, and other sundries dry amid a constant deluge of rain and sea spray?

Answers to those questions: We bought Wild Card, a 1976 racing boat with a turquoise hull that had previously completed the R2AK and was a minor celebrity in the Pacific Northwest racing community. We found a brave volunteer to sail Wild Card back from Ketchikan to Bellingham, and would ship the outboard up on the ferry for him. We would eat dehydrated meals donated by Backpacker’s Pantry, and oodles of snacks such as jerky, chocolate and nuts. We would pee in a bucket and dump it overboard. We would bring 28 gallons of water in four jugs. And we would pray fervently that oversize plastic bags and good luck would keep our gear sort of dry.

But first, we had to see if our application would pass the race committee’s muster. The R2AK’s laissez-faire attitude on rules doesn’t extend to letting just anyone compete.

“The vetting process is something we take really seriously,” Wiegel says. “It ultimately boils down to: Do you have what it takes to keep yourself from getting killed? Do you have the judgment to make good calls, even if it’s sometimes going to be the call to quit?”

Our team definitely took the “keep yourself from getting killed” part seriously. We’re mothers, after all. We borrowed a life raft, installed personal locator beacons and lights on our life jackets, mounted a SailProof tablet in the cockpit to navigate easily in all conditions, attached an AIS transmitter so that cargo and cruise ships would see our tiny boat in big seas, and practiced a lot of woman-overboard drills. We had extra pedals, extra tools, backup navigation lights, backup batteries to charge them, and a medical kit that could outfit a small village.

But that didn’t mean I didn’t worry. After sailing more than 10,000 miles across various oceans, I know that stuff goes sideways. Like that time a decade ago when I had to dive overboard in a shipping lane to pull bull kelp out of the engine’s intake while the boat spiraled in a whirlpool amid pea-soup fog. Or the time our mainsail ripped while my family was sailing closehauled in a motorless Sea Pearl in the Bahamas (with me four months pregnant and our 3-year-old napping in the cockpit). That time, we managed a controlled shipwreck on a sliver of sand amid sharp coral to avoid getting sucked out to sea. And don’t get me started on all the times our engine has died, the electrical system has fritzed, or a line has jammed at the worst possible moment—usually right around 2 a.m. in a squall.

When things get hairy, I’ve learned to deal calmly. To think carefully about potential next steps. To rely on the skills of the friends or family beside me. And, most important, to pull the plug if our combined skills are no match for the problem at hand. Our team motto for getting to Ketchikan was easy to agree upon: “Push ourselves, but be safe and have fun.”

Of course, fun is relative on the R2AK. My first time flying the spinnaker was a perfect example of that: Wait five minutes, and the weather will change. Wait another five minutes, and your sky-high confidence will plummet to the seafloor. We faced big winds and opposing tides. We beat for hours and hours (and hours) up Johnstone Strait in 25 to 30 knots of wind—which was, in all honesty, harder than childbirth. We accidentally jibed in the middle of the night way, way too close to a rock in the roily waters of Hecate Strait while careening down 6-foot swells. We ran out of water in the Dixon Entrance and were too tired to eat after sailing 40 hours straight to the finish line. And we changed headsails 7,458 times, give or take.

But we also saw orcas at sunset and bioluminescence under a full moon. We hobbyhorsed happily over the whitecapped swells on an easy reach all the way across the Strait of Juan de Fuca. We laughed a lot more than we cried. And by the end, we flew that beautiful black spinnaker like it was second nature.

On Day 9, we decided to head offshore in hopes of riding steadier south winds the last 140 miles to Alaska. We also, it turns out, got surprisingly competitive at the end. A handful of teams had been leapfrogging us the last half of the course, and we knew that we could beat them if we took the open-ocean route instead of the winding inside channels.

But keeping pace with those teams also boosted our morale along the way, especially our daily VHF radio chats with soloist Adam Cove on Team Wicked Wily Wildcat.

“One of my biggest wins from this race was the level of camaraderie,” says Cove, who snagged two R2AK records this year: fastest singlehanded monohull and fastest monohull under 20 feet. “It’s nice to know that if something goes wrong, we’ve got one another’s backs.”

As an avid offshore and coastal racer on the East Coast, Cove said that the R2AK was the most challenging race he’s ever done. The captain of this year’s first-place winner, Duncan Gladman of Team Malolo, agrees.

“The R2AK has every difficult element,” Gladman says. “You’re constantly navigating. The weather is constantly shifting. And it just gets harder the farther up the course you get.”

Gladman is well-versed in the unpredictable nature of the R2AK. He attempted the race aboard the same trimaran twice before, only to be crushed (literally) by logs. The third time was the charm: His team finished in five days this past June.

On Day 10 of our voyage, we saw the light at the end of the tunnel—or, in this case, the narrow channel that was our exit for Ketchikan. Dall’s porpoises ushered us through the last rolling swells of the Dixon Entrance. Even in my disheveled, hangry-zombie state, it still took all of my willpower not to push the tiller to starboard and head south to Hawaii. I wasn’t quite ready to say goodbye to the rhythm of our days aboard. But we held our course, enticed by hot showers, a real toilet, dry beds and the warm welcome awaiting us.

When we rang the bell at the finish line at 1:03 a.m., the dock was brimming full of fellow racers and well-wishers. I cried happy tears and hugged my teammates.

And then I promptly started planning my next sailing adventure.

Fear the Grim Sweeper

The R2AK committee isn’t playing around. It’s a race, not a leisurely stroll. The trusty sweep boat, affectionately dubbed the “Grim Sweeper,” is on the move as soon as the first racer reaches Ketchikan, or by June 21, whichever comes later. From Port Townsend, it cruises north at about 75 miles a day. If you see it heading your way, you’re out of the race. They’ll collect your tracking device and say hi, but don’t expect a free ride to Ketchikan. They can help you figure out your next steps though. —CW staff