Eibbor and Knarf’s parents were kidnapped by Frost Giants. The boys desperately needed help. Scooter Squirrel raced to Winston Woodchuck, who dived into his burrow, frantically digging until he reached the tunnels of the Dwarves. They summoned Frey, who came with his longship, Skidbladnir, and took the boys to Asgard to plead their case to Odin. Skidbladnir was enchanted so that, among other magical traits, it always had fair winds and got where it needed to go.

Such were the bedtime stories Dad told my brother, Frank, and me more than 60 years ago in the wild hills of West Bolton, Vermont, overlooking Lake Champlain. Despite the US Navy being born on Lake Champlain and the famous Capt. Phillips living a few miles from our house, Vermont is the only landlocked state in New England, so it might not seem an apt setting for nautical lore and traditions. However, a few years after my grandfather returned from World War II, he and my then-preteen father built a 16-foot Moth and ignited an obsession in Dad for sailboats. He found plans for a 26-foot ketch that became his lifelong white whale. I grew up with those plans and, under Dad’s tutelage, learned almost every rig that had sailed for the past thousand years by copying illustrations in The Book of Old Ships by Henry B. Culver and Gordon Grant.

My initial 20 or so were canoes. I bought my first canoe with my paper-route money at age 11 and got a Gunter-rig sailing kit. That Grumman canoe still hangs in the barn in the winter, but in 55 years, it has never had a name. My first experience with naming a boat was as a teenager, when a 16-foot Rocket-class sloop that had been in a chicken coop for 25 years was donated to our Explorer post. We restored her and sailed the chickens—I mean the dickens—out of her on Lake Champlain. Our best adolescent workmanship notwithstanding, her seams could work the caulking in a chop, and we named her Kon Liki. It was 39 years before I named a second boat.

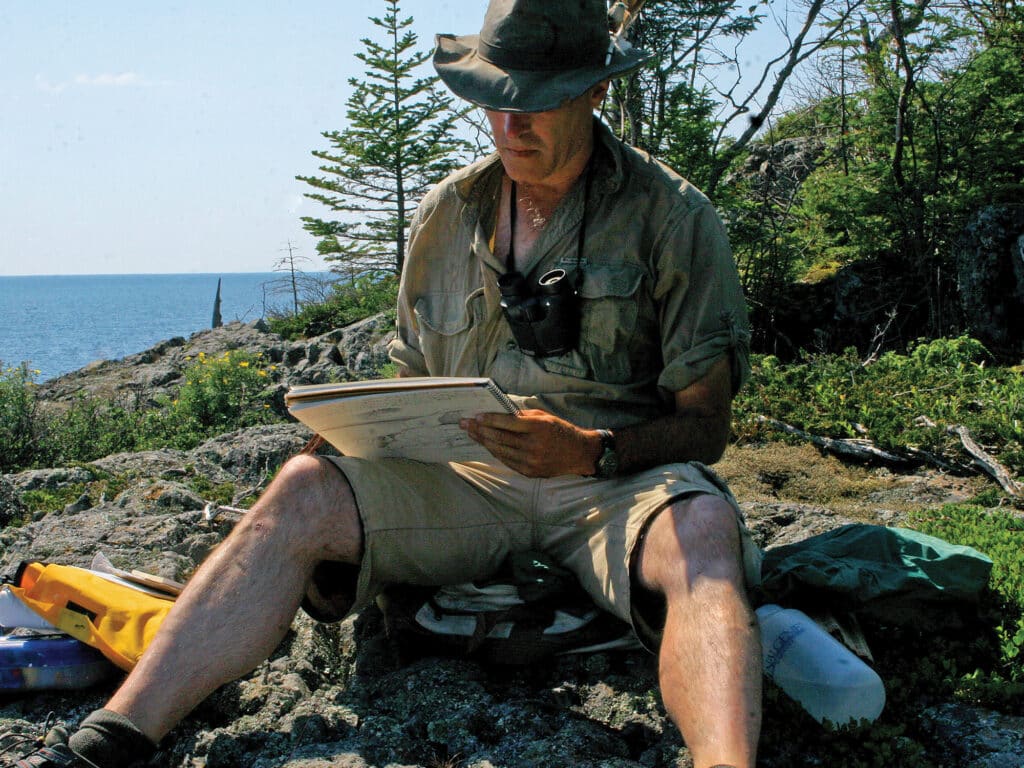

On the cusp of October 2009, another artist, Cole Johnson, and I stood at the lip of the 1,200-foot canyon of Canada’s Kogaluk River (“Little River” in Inuktitut) with our canoe in the howling wilderness of the Labrador Barrenlands. A river we’d been on nine days earlier had wandered into a boulder garden and had not come out, so we struck out overland, north to the Kogaluk, hoping that it would have water. As we stood, buffeted by the gale winds of the Barrens, it was a profound relief and joy to look down to the sparkling river far below. At that moment, a feeling welled up to name our silent companion, the stalwart canoe that would, days later, on the Labrador Sea, save our lives. The name came to me instantly, Bonnie, my then girlfriend, now wife (it was also, by chance, Cole’s mother’s name), steadfast and true no matter the challenge. That was one of only two canoes I have ever named.

After COVID struck and closed Canada, I was stuck in Vermont, so I hiked the 273-mile Long Trail end to end as a painting trip. The paintings from the hike sold out so, in 2021, I decided to do the same thing on Lake Champlain. But I needed a bigger boat. I found a wooden, double-ended, 20-foot pocket cruiser (appropriately for my transition back to sail, a “canoe yawl”) at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum. It was essentially a nice trailer with a free boat on it. Bonnie and I spent two months restoring that boat. I’d planned to spend at least six weeks aboard, so the boat needed a name. We bandied several about as we sanded the boat to bare wood, sealed the hull, and built accommodations in the cabin. Years ago, I had toured on the national art show circuit in a 15-passenger Dodge van dubbed the Artful Dodger. This boat was cute and a bit plump, but well-rounded with lovely lines. As a sleek creature of the water and my nascent floating studio, it almost named itself the Artful Otter.

The voyage of the Artful Otter was a wonderful experience during which I named my second canoe, a tubby 11-foot bright-green cutie that Bonnie had owned since childhood. That was the canoe that helped bring us together (another story), and I used it as Artful Otter’s tender. With the tiny green boat trailing lightly behind on the waves, its name became obvious: Leaflet.

The voyage raised funds for charities and made the artists some money. Expanding from the idea of the Long Trail trip, I involved other artists who all wanted to continue the project, so we needed a yet bigger boat. I cruised the yacht websites looking for an affordable, artistic vessel. That turned out to be a tall order. Brother Frank, now a retired US Coast Guard captain, steered me away from a couple of old wooden beauties that appealed to the artist in me but would have probably sunk—my plans, anyway.

Then, I found it: a wooden, 1962 Aries 32 ketch in Chester, Nova Scotia. A double-ender like Artful Otter, this boat underwent a marine survey that impressed even sea dog Frank. And I could afford it by selling Artful Otter. That was a painful thought. Nonetheless, I brought the printout of the listing down to dinner, the one meal that Dad, Bonnie and I share every day.

Dad is an old-time Vermonter with Yankee frugality deeply ingrained, so I never saw his reaction coming. He had gotten his teenage ketch plans out while Bonnie and I restored Artful Otter, but presumably the enormity of the project hit, and he had not proceeded beyond that. Looking at the photos of this ketch at dinner, though, he set his jaw and quietly said, “That’s my boat.”

“Huh?” I started to explain the plan when he cut me off.

“Don’t sell the Otter. I’ll buy this boat,” he said.

And that was that. I suspect that, at age 90, he was realizing that lifelong dreams needed to come to reality ASAP, and he would not discuss it.

Chester, Nova Scotia, is at least a 1,200-mile sail back to Vermont. After dinner, Bonnie upped the ante with the idea of Frank and me taking Dad on a bucket-list trip of a lifetime by sailing home with him in the ketch. He will be 91 when we get underway in July, but his mind is sound, and he is healthy and strong. Frank jumped aboard immediately, and I’ve never seen Dad so enthused.

Rub-a-dub-dub, three old men in a…well, the boat needed a name. Yet apart from a brief inspection in a heavy snowstorm, I had no physical connection with the boat. My names for other boats had been bestowed organically, but this time, it seemed, we might need to dream up one out of thin air.

Artful Otter II, the working name during the search, was jettisoned instantly, closely followed by my overlong fixation with plays on art and ketches such as Sketchy Otter, Art S’Ketch, Sketch-A-Ketch, CanUS’Ketch (Bonnie is Canadian) and other such ideas. Sea dog Frank thought my Bonnie Pearl was a wonderfully nautical play on Captain Jack Sparrow’s Black Pearl and Bonnie. Dad was politely nonplussed.

Then, it hit me. The three of us setting off on an adventure: Eibbor and Knarf stories, Scooter Squirrel, the Dwarves, the Norse gods, and a magic longship, like a double-ender ketch.

As is true of many Germanic-language names, it is not pretty to an American (or Canadian) ear, but it resonates with the three of us 60 years later: Skidbladnir.

Hailing from Lake Champlain, wildlife artist, naturalist, and outdoorsman Rob Mullen operates out of his floating studio, the canoe-yawl Artful Otter. Lately, his sailing and painting grounds have grown to include the 1962 wooden Aries 32 ketch Skidbladnir.