The blue Travelift puffs and rumbles. Muffled voices bray above the engine. I smile because I recognize those voices. In the weeks that I’ve been stalled at Mile 403 on the Intracoastal Waterway with engine problems, I’ve met a whole group of people—boat people. And many have become friends.

Now I’m ready for my morning sausage biscuit and endless coffee in the air conditioning at McDonald’s, so I close up the boat and unlock Dr. John’s old black bicycle.

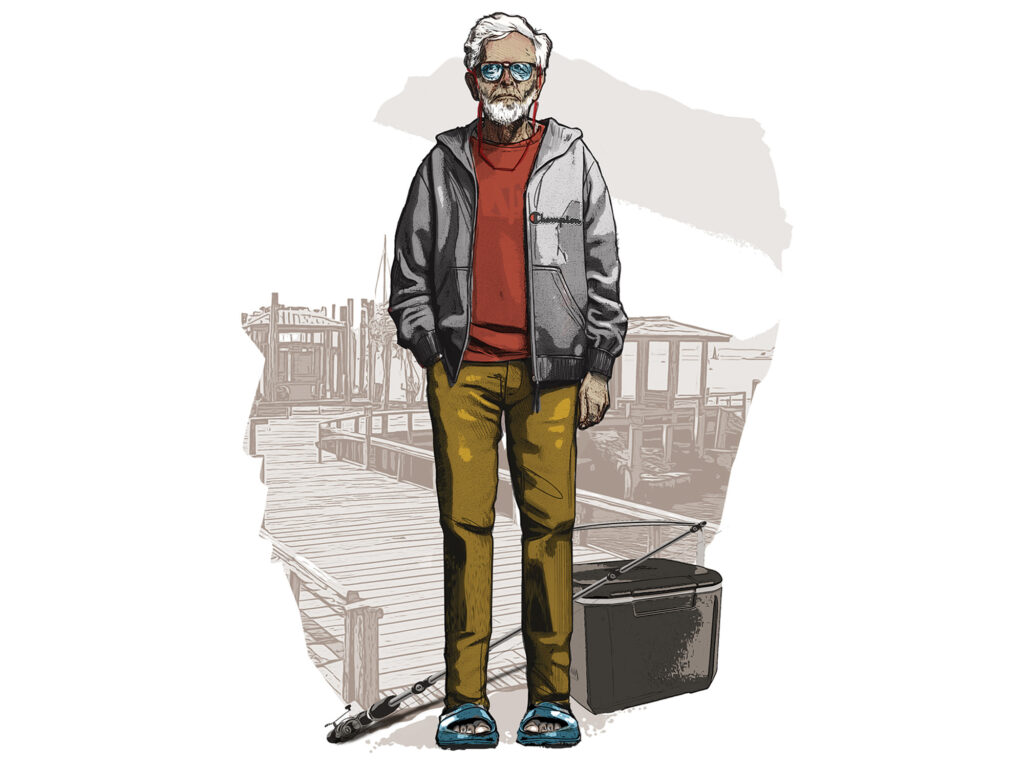

The Doctor

“It’s rusted, has flat tires and a broken spoke,” he said as he handed me the key. “Just make sure you lock it up.”

Dr. John is an even-tempered retired doctor from Kentucky. Seventy-something, tall and spare, with thick glasses tied to a lanyard around his neck, he has the craggy look of Abe Lincoln after an all-night poker game. He lives on a 40-foot lug-rigged steel schooner, a Colvin Gazelle, tied up on the end dock in the back row.

We’ve become good friends, probably because we’re the only full-time live-aboards in the marina. He rarely leaves his boat. Instead, he spends his time below, day-trading foreign currencies, wagering his pension into the wee hours of the morning. Right now, he’s probably sleeping off an after-hours trading session.

I’ll find out the results later. We usually meet up for dinner. He’s had a down streak lately, which means we’ll both be dining with $1 Burger King coupons tonight. Again.

The Mayor

The Harborwalk is along the waterfront in Georgetown, South Carolina. Several local boats are tied up there, fishermen mostly, but you’ll occasionally find a transient cruising boat or a liveaboard among them. A hand-painted sign declaring “Don’t Feed the Alligators!” reminds the visiting northern cruiser that he’s far from home.

Next to this boardwalk is an upscale seafood restaurant, and I was standing outside the entrance drooling over its menu: blackened yellowfin tuna, boiled local shrimp, definitely the jalapeño cornbread. And definitely out of my $3-per-day budget.

I lit one of my cheap Swisher Sweet cigars and was soon clouded in cherry smoke. A tall, well-dressed fellow came out of the restaurant. Blue oxford cloth shirt, pressed chinos—a style that used to be called preppy.I glanced up, and when I realized he was looking my way, I nodded.

He sniffed the air. “Is that a Swisher Sweet?” he asked.

He turned his head and looked back at the restaurant. I know that look. That’s a Where’s the wife? look. “Would you have another one?” he asked. “I hate to bother you.”

I shook the box and offered him one. He unwrapped it, and like a kid sneaking a smoke (I know that look too), he asked for a light.

“Are you on one of the boats?” he asked. I guess the stained cargo shorts, flip-flops and sunburned raccoon eyes gave me away.

“Yeah, but I’m stuck here for a while. Engine problems.”

We walked, and he asked about my boat, my trip, my sabbatical from school. “I thought about being a teacher,” he said.

“Oh? Well, what do you do?”

“I’m the mayor of Georgetown.”

I was taken aback. “Well, Mr. Mayor,” I said, “this sure is a nice little town you’ve got here.”

“Thanks,” he smiled. “And good luck with that engine.” Then he turned down a side street and walked off into the warm evening.

The Captain

Surprisingly, another one of those little cigars paid my dockage for a month.

That fiendish Perkins 4-108 devoured parts, time and money. I’d moved Traveller from the transient dock to the back row because it was cheaper. The boats along the back row grounded out in the mud at low tide, but that didn’t matter; most of them never left.

It was a hot evening, and even with all the hatches open, the little 12-volt fan was straining. I took my little box of cigars and walked to the transient dock to get some breeze.

Out in the channel, navigation lights shone, and a dark, looming shape got larger.

Slowly, a motorcruiser approached. As it got closer, a row of white deck lights flashed on, revealing a small woman in a long dress holding a coil of rope. The captain throttled back, but at the last moment, he must have thought better of his landing. He passed the dock, made a big circle and tried it again. I noticed that the hailing port was Portland, Maine.

The woman spoke into a handheld radio as the captain eased the big boat alongside. Bow thrusters, I thought. He had the stern line and spring lines ready to go.

“Happy to take the stern line,” I said.

The captain handed me the stern line, then planted a plastic step on the dock and lumbered onto it. He walked forward to make up the bow line. The lady in the long dress hurled a snide remark along with the bow line, then walked back into the cabin.

“My wife,” he said. “Just the two of us on board.”

He made up the spring lines. “Thanks for your help.”

They were on their way to South Florida, but they’d hit something about a mile back. “Something’s not right under there,” he said. He was brusque and beefy, with a gruff voice that was used to giving orders and having them obeyed. And no wonder. It turned out that he owned a commercial boatyard on the Portland waterfront. In a world of fishermen, welders, engine oil and swearing, he was the man who signed the checks.

“Are you on one of the boats?” he asked. I guess the stained cargo shorts, flip-flops and sunburned raccoon eyes gave me away.

As we spoke, I relit my little cigar. “I’m from Kennebunkport,” I said.

“Ha! Small world, huh?” he said, eyeing the flame. He lowered his voice and looked over his shoulder. “Say, you got an extra one of them smokes?”

The next morning, the big cruiser was already hauled out when I went up for a shower. The captain was sweaty and directing the work. He had enlisted two young fellows from another transient boat to help, and they were following his orders, struggling with a bent propeller shaft. A yard crew was pressure-washing the parts.

The captain saw me and waved me over.

“How’d you like to make a quick hundred bucks?”

My dockage bill was due soon. “What do you need?”

He needed me to drive the bent shaft to a machine shop in Wilmington, North Carolina, drop off the damaged shaft, and return with a replacement. It would take most of a day. It wasn’t even 9 a.m., and he’d already made the arrangements. “I’ll pick up the old one on my way back up to Maine.”

“No problem.”

“But I need you to go today, like right now.” He took out a thick wad of bills and counted a few into my hand. “That ought to cover gas and lunch,” he said.

When I returned with the new shaft, the yard was closed, but the captain and his two helpers were still fussing with the struts and rudders. He saw me drive up. “Got it?” he barked.

Thumbs-up.

He walked over to inspect the replacement. He scrutinized the threads, the keyway. “Looks good,” he said.

The other two helpers walked over to take a look. One of them said, “I think we can slide that right in tomorrow morning.”

“Let’s meet here tomorrow morning at 8,” the captain said. “Now, you boys ready to eat?”

We cleaned up and met the captain at that fancy restaurant on the waterfront. Mrs. Captain declined the invitation.

“Dinner’s on me tonight, boys. Thanks for your help with the boat. Now, where’s that waiter? We need some beers.”

The beers arrived. Then another round. Finally, we looked over the dinner menus. I ordered the blackened yellowfin tuna. And the cornbread.

The Detailer

“Now, Karla, she knows something about gelcoat repair. She’s who you should talk to.”

I was in the air-conditioned captain’s quarters, and the yard crew was wolfing down forkfuls of pork barbecue and green beans from white plastic-foam boxes. At their feet, each man had a gallon jug of cold sweet tea. Couldn’t blame them. It was over 100 degrees out there.

“She’s out there workin’. Never stops for lunch.”

In the yard, Karla was standing on a three-step ladder behind a curtain of powder, buffing the topsides of an old Grady-White. She was a puffy little figure in a white Tyvek suit, goggles, mask, gloves and blue flip-flops. The off-white gelcoat looked factory-original. She was using a big Makita buffer. As I approached, she switched it off.

“Looks great,” I said.

“Getting there.” She pulled up the goggles, her dark eyes raccooned by white powder. I could just make out some blond hair within the hood.

“I’m Dave,” I said.

“I know who you are. You’re on that old sailboat with…”

“…with the beat-up topsides,” I chimed in. “I was wondering if you might take a look, give me some ideas on what to do with it.”

No response.

“I’d be happy to buy you lunch.”

She gave the Makita a whirl. “Lunch, huh?”

The next morning, someone knocked on the hull. I slid back the hatch. Karla was kneeling on the float in fashionably distressed blue jeans, a straining red tube top, and cowgirl boots.

“Is this what you’re talking about?” she asked as she moved one hand along the scratched and scarred surface of Traveller’s topsides. “That can be fixed.” She stopped and examined a gouge. “Looks like the original gelcoat was dark blue.” She looked up through her big, round sunglasses. “Can I see the cabin?”

I felt like the fly letting in the spider. She slipped off her boots in the cockpit and then padded down the companionway steps in bare feet and scarlet nail polish. She stopped, looked around. “Uh-huh.”

She continued around the salon and slunk up forward, looking under cushions and talking as she went. She told me how she’d learned about gelcoat from her dad, a classic car restorer. She told me how her husband had fallen off a roof and couldn’t move. She told me that she’s a religious woman. She told me how a woman has needs. She told me a lot more than I wanted to know.

“Do you have a girlfriend, Dave?” she asked as she opened the door to the head.

“Yes, I…”

“Oh Lord, no!” she cried out. She was all business again. “This is not right. Not at all. There’s black mold all up there. You shouldn’t be breathing that! Have you been breathing that?”

“Well, I….”

“No! You need to get you a bucket, some water and bleach. Rubber gloves! A mask! Take a Magic Eraser, and clean allof that. It’s gotta go!”

That night, I slept in the cockpit because the boat reeked of bleach. The cabin cushions were all lined up on the side decks, airing out after their scouring.

The next week, Karla hired me and another marina guy for a big detailing job. The week after that, she stiffed me on a smaller job. The week after that found me at the local library, printing out business cards for my startup boat-cleaning business.

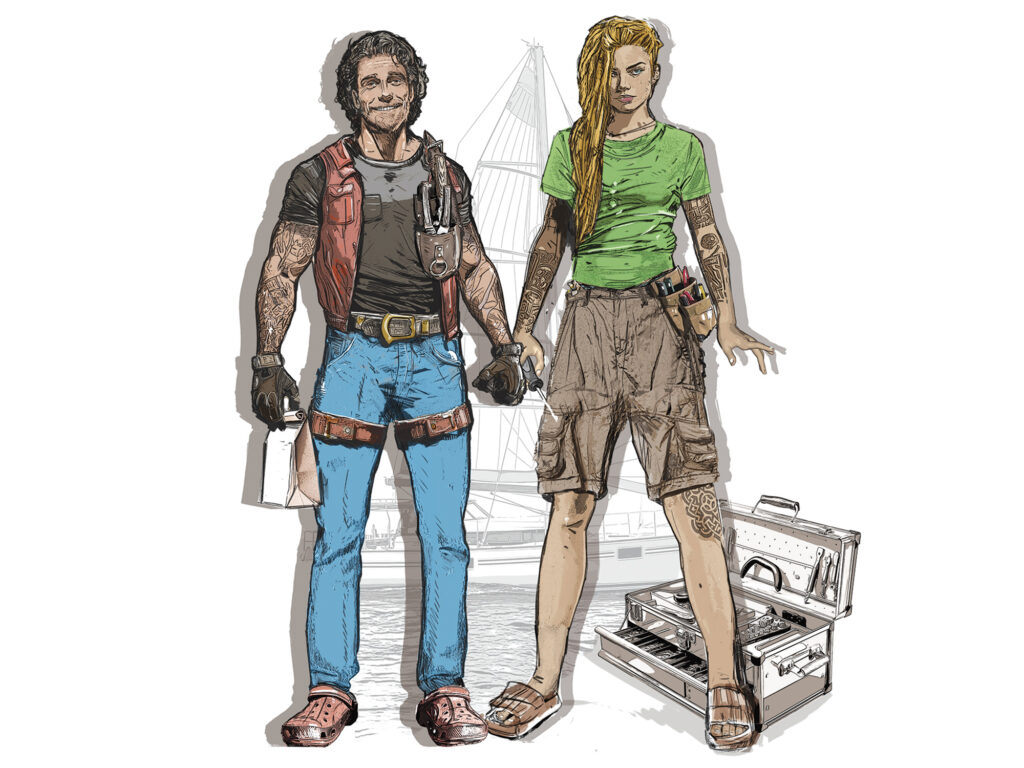

The Happy Couple

I was working at the Annapolis Sailboat Show, standing at the front gate with a juvenile delinquent named Charles.

Charles was from Baltimore. Charles was on probation. We were both strapping orange wristbands around people’s wrists as they pushed in to see the new Beneteaus and Bavarias.

“The important thing about prison,” he drawled, “is you gotta be part of a group. A gang. Or the Jesus people. Me, I was lucky. I’m an artist. They left me the hell alone.”

“Artist?” I asked.

“Tattoos, man. I’m a tattoo artist,” he said as he launched into a detailed description of how to make a tattoo gun out of an old CD player. It was surprisingly simple.

The majority of the boat-show workers were long-distance cruisers. Many were retirees with big boats. All were waiting for the calendar to flip so they could satisfy their insurance policies and head down to the Florida Keys or the Caribbean after hurricane season.

Each show worker was on a crew: docks, waterfront, construction, electrical. I drove a utility boat on the waterfront crew. We each got a free lunch during the boat show, so later, we were sitting at a long picnic table enjoying our sandwiches and coleslaw.

“Kinduva small boat for them two, don’t ya think?” This from Frank, a dock-bound, waterfront guy. “They go out sailing every evening,” he continued.

“Who you talkin’ about, Frank?” I asked.

“Them two over there, ’lectrical crew.” He pointed his plastic fork toward Greta and John.

She was tall and blonde, with an easy smile and the long, powerful arms and legs of a Viking queen. A heavily tattooed queen. John’s hair was dark and unruly. He was muscular and medium height. His arms were also covered with tattoos. This Midwestern couple lived on their boat, a Catalina 25 that they had bought online for $5,000.

They approached us carrying trays, so I hailed them over. John was happy to relax, happy to retell the story of their find. “Oh, the outboard was cranky, but we got it running OK. I used to work as a truck mechanic.”

“Mostly, I like that it’s paid for,” Greta added. “Everything we make here can go right into our cruising fund.”

That’s a couple thousand bucks. Each.

“And you didn’t know how to sail the boat when you bought it?”

“Nope. Still don’t!” They laughed. “Where we live, there’s no sailing. But John got the bug, and well, it was catching. He was convincing, so I thought, Why not? Let’s go to the Caribbean. We’ll figure it out as we go along.”

And there it was. That essential attitude that moves us forward: We’ll figure it out as we go along. It’s the same attitude that the majority of these retiree captains have as they learn about every system, every fitting, and every machine they install in their boats.

I could imagine these two characters slipping their mooring, outboard gurgling, finally getting into an open patch of water, then hoisting the main and shutting down the engine. The two of them: Greta holding the book and reading aloud, John following her directions and experimenting with how tightly to sheet in the jib. Their delight when the boat accelerates. Their panic from an unexpected jibe. Their talk at night about finding hidden Caribbean anchorages. Maybe some pirate treasure?

You had to admire them, and maybe be a little envious. Of all the people I had met along the way—and there were many—those two were really living the dream.