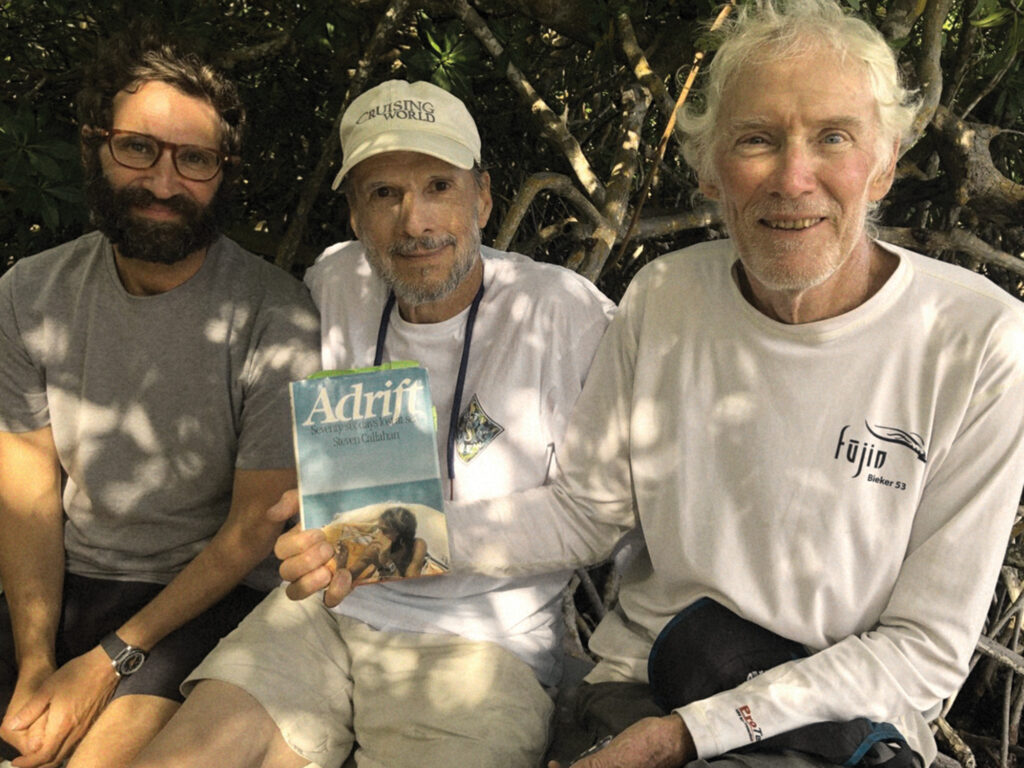

It was a little pool, of course, but he had set it up with all the props that he and former Cruising World senior editor Steve Callahan had spent the previous year collecting from boat chandleries, websites, and wherever else they could find them. They were about to fly down to St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands to film a documentary based on Callahan’s New York Times bestselling book Adrift: 76 Days Lost at Sea.

“I went through everything I knew I would need, and I set up a rig that would be waterproof to get the shots I needed,” Wein says. “People asked me, ‘What kind of sea legs do you have?’ I told them I’d be fine, but I really didn’t know. I was definitely nauseous the first couple of days, but I had to get these shots.”

They were determined to bring the book to life nearly 40 years after it was published in 1986, detailing how Callahan had to abandon the 21-foot sailboat Napoleon Solo, which he had designed and built. He ended up struggling to stay alive on the life raft for more than two months. He’d been participating in one of the first editions of the Mini Transat Race when something, likely a whale, struck the hull.

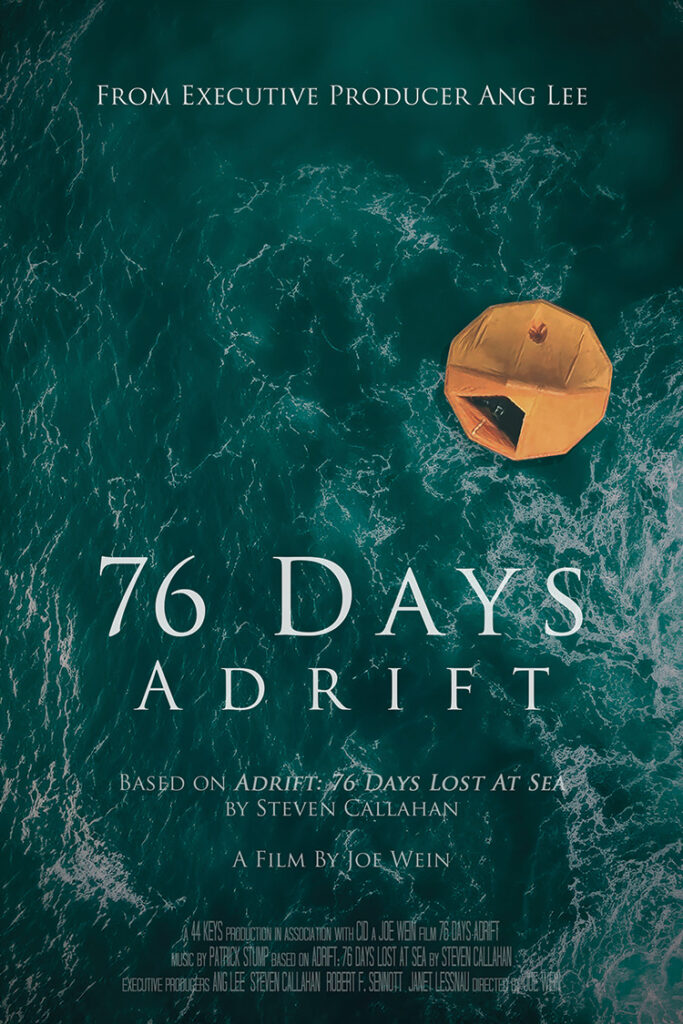

The book, and Wein’s new documentary 76 Days Adrift, are about how Callahan survived as well as what he learned out there all alone. Wein’s vision for bringing the book to life was the first one Callahan had seen in all the ensuing years that got him excited.

And he was far from alone in embracing Wein’s vision. Academy Award-winner Ang Lee, whom Callahan knew from being a consultant on Life of Pi, signed on to 76 Days Adrift as an executive producer. Patrick Stump from the rock band Fall Out Boy wrote an original score that was recorded by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. The song that plays over the film’s credits at the end is also by Stump, a cover of Iggy Pop’s hit tune “The Passenger.”

“I’d seen some scripts, and frankly, I thought they were pretty bad,” Callahan says. “They were quite sort of typically Hollywood memes and whatnot. And Joe came to me and said, ‘You know, I would like to do a documentary on it,’ which lends itself to having some authenticity.”

Wein says that he wanted that kind of authenticity in the filmmaking because Callahan had only certain items he could work with in the life raft. He could use only whatever he had thought to include in his safety preparations before leaving shore on the boat. When Wein read Callahan’s book, he says, he realized how important the choice of those items had been.

“Every choice he makes is a life-or-death choice, and he has to keep making choices,” Wein says. “I found myself trying to really keep an inventory of what he had. So in the documentary, I really do the best I can to have it all exactly right.”

Wein and Callahan looked everywhere they could think of to find, for instance, the type of solar still that Callahan had on the raft all those years ago. They scoured websites and asked around, always coming up short.

Then, Wein says, he found somebody selling what was described as a post-Vietnam solar still, as a collector’s item. He showed it to Callahan, “and he said, ‘Oh my God, that’s the exact one.’”

Finding the same life raft took a year. Wein kept buying rafts as he could get his hands on them, basically building a mountain of unusable options where he lives in California.

“My wife was like, ‘Look at all these rafts in my house,’” Wein says. “But none of them was the right raft. Finally, the exact raft from the exact time period came into Avalon Rafts in Long Beach. They couldn’t use it, and they knew I was looking for it.”

There was the spear gun. The Boy Scout utility tool. It was so much stuff from decades ago that friends and family members ended up participating in a type of scavenger hunt, trying to help them find it all.

“We spent weeks debating over what kind of a compass would it be, that would be period-perfect,” Callahan says. “And how do we get water cans that are period? We ended up having to have those manufactured.”

Finally, they were ready for the 17 days of filming off St. Croix. Callahan had hooked up with his friend, Roger Hatfield, co-founder of Gold Coast Yachts. Roger and his partner lent the film crew a boat, giving Callahan a chance to experience what had happened to him from an angle that boaters rarely get to see.

– CARRY A BEACON –

Safety Tip Provided by the U.S. Coast Guard

Satellite beacons such as EPIRBs or PLBs allow boaters to transmit distress signals and their exact coordinates from anywhere on the planet, no cell service required. It may be the best $400 you ever spend.

“That was very interesting for me, because, of course, I saw it from my own point of view, but now we had drones and boats and stuff that we could look at, the raft and everything from off the raft,” he says.

Wein wrote the screenplay based on a week’s worth of interviews that he did with Callahan—after Wein spent six weeks breaking down Callahan’s book and preparing all kinds of questions that could help turn Callahan’s own writing into a documentary film. It turned out that Callahan also still had the original journal that he’d kept out on the life raft, so that was integrated into the screenplay too.

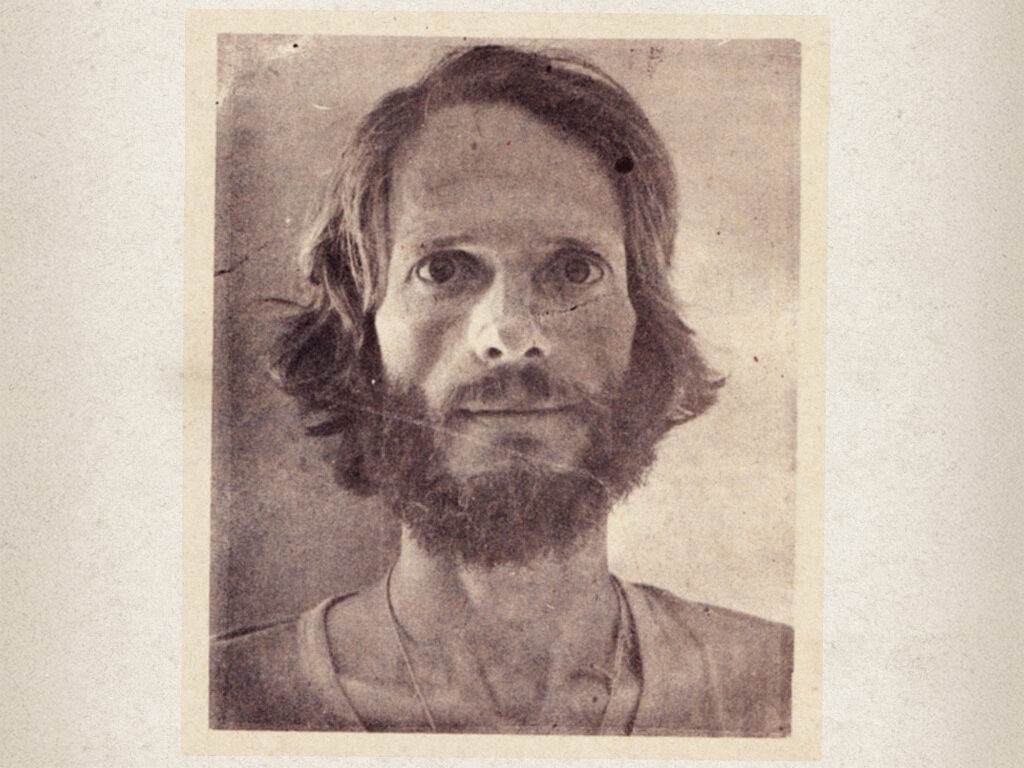

Callahan narrates the film while Wein re-creates what Callahan did. Wein lost 20 pounds and grew a beard for the shoot, just in case the camera captured a flash of him from any possible angle, to make everything feel authentic for the viewer.

“I wanted to have it be a real experience,” Wein says, explaining that he approached the filmmaking differently from the way a lot of documentaries are made. “There’s all this pressure to bring in multiple interviews, talk to academics, all these people who were involved, but if I have to explain to you that this was a hard situation, then I’m not contributing anything. You should be feeling this experience.”

They also had to figure out how to make certain scenes come to life without triggering a search-and-response cavalry out on the water. In one scene, Callahan explains how he lighted flares under the darkness of night, trying to summon help to his life raft. Wein wanted to re-create this moment for the documentary, but it would require, well, sending up a bunch of emergency flares off the coast of St. Croix.

Callahan asked Hatfield if he could talk to some friends at the US Coast Guard, and Hatfield was able to help the film crew get permission. “So we went out to the bay, anchored, and set Joe off into the raft,” Callahan says.

Their VHF radio then lit up with reports from concerned citizens trying to alert the Coast Guard that somebody was in trouble.

“Joe’s out there firing flares, and all of a sudden we’re getting all this chatter from shore,” Callahan says. “‘There’s somebody out here on the reef,’ stuff like that. The Coast Guard had to say: ‘No, no, no, that’s all right. That’s fine. It’s fine.’ But there must have been four or five reports, so it was a good thing to know that passing boats and people on the shore, people are actually looking out and saying, ‘Hey, guess what? There’s a flare.’”

For Wein, one of the most interesting parts of making the film was learning how to tie knots. He’s a landlubber who never realized just how much an experienced boater like Callahan can do with the ability to tie different kinds of knots.

– CHECK THE WEATHER –

Safety Tip Provided by the U.S. Coast Guard

The weather changes all the time. Always check the forecast and prepare for the worst case.

That viewpoint, Wein says, is helping audiences who have no experience on boats appreciate Callahan’s ordeal in all kinds of ways.

“I’m the outsider, and I think it makes it a more universal movie that way. I’m trying to figure out what a conical plug is, and what are these kinds of knots?” Wein says. “I actually really appreciated the importance of being able to tie knots, just in everyday life. He could do so many things with twine.”

The ability that so many boaters have—to be able to work through a big problem, one solution at a time—is resonating with people who see the film, according to executive producer Rob Sennott. The filmmakers have been doing live Q&As after some showings at film festivals, and audience members have been telling them that the documentary touches their hearts in the most tender ways.

– UPGRADE YOUR RADIO –

Safety Tip Provided by the U.S. Coast Guard

Digital Select Calling (DSC) allows you to transmit your precise location with the press of a button. Make sure your VHF radio has it, and don’t forget to get your MMSI number. It might just save your life.

“Several times people have, during the Q&A, admitted that this film has helped them psychologically with their lives,” Sennott says. “It’s like, you know, if Steve can get through this, I can get through what I’m going through right now.

“One woman in the audience confided that she had some mental health issues, and this film really helped her kind of gain a perspective on what she was going through,” he adds. “This film is very inspiring for audiences.” •

To learn more about the documentary or to see where upcoming showings are planned, please visit 76daysadrift.com.