If you’d like to buy a cruising vessel, I recommend the classic five-step approach.

Step One: Decide what type of cruising you’re interested in.

Step Two: Research the market for suitable vessels.

Step Three: Talk to owners of those specific vessels for a reality check and, with the help of…

Step Four: a broker, and Step Five: a surveyor, sign on the dotted line.

That’s my advice.

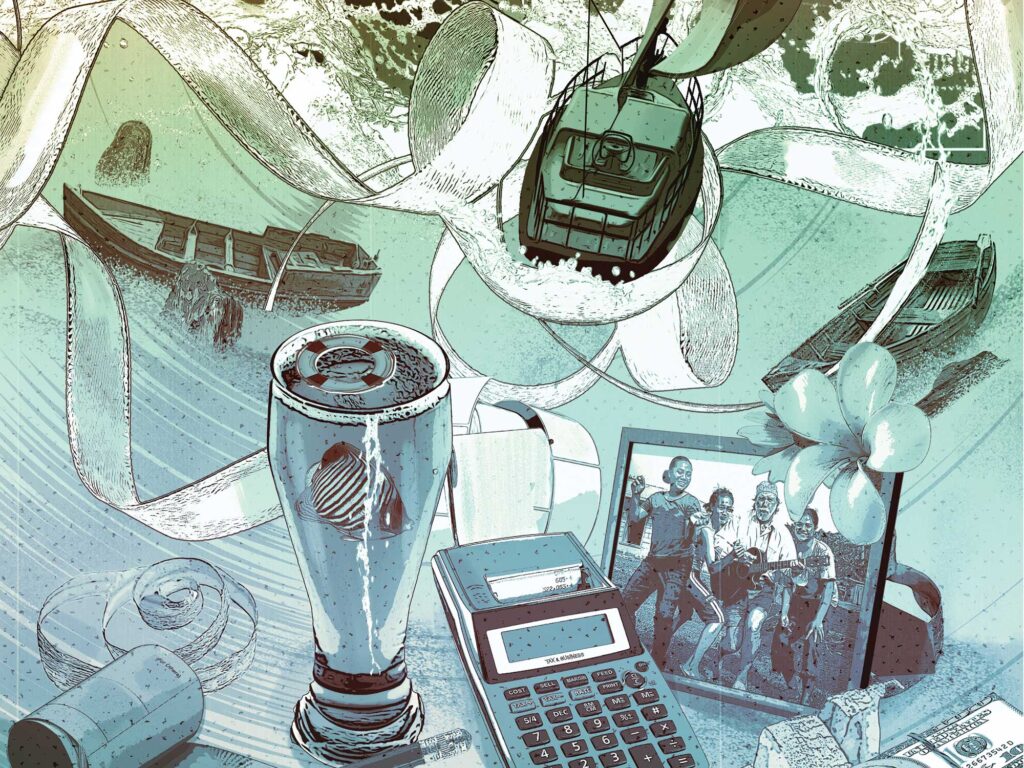

However, I’d be disingenuous if I said that’s how I do it. I look for a worthless boat with a major problem and a ticking clock, and then assist the owner in getting on with his life by taking the vessel off his hands for a token, face-saving payment.

How to find a worthless boat is easy. It is one that hasn’t sold for a year or three. Just look at two-year-old ads for boats that you’d like to own, and see if the boats are still for sale. If so, they’re worthless.

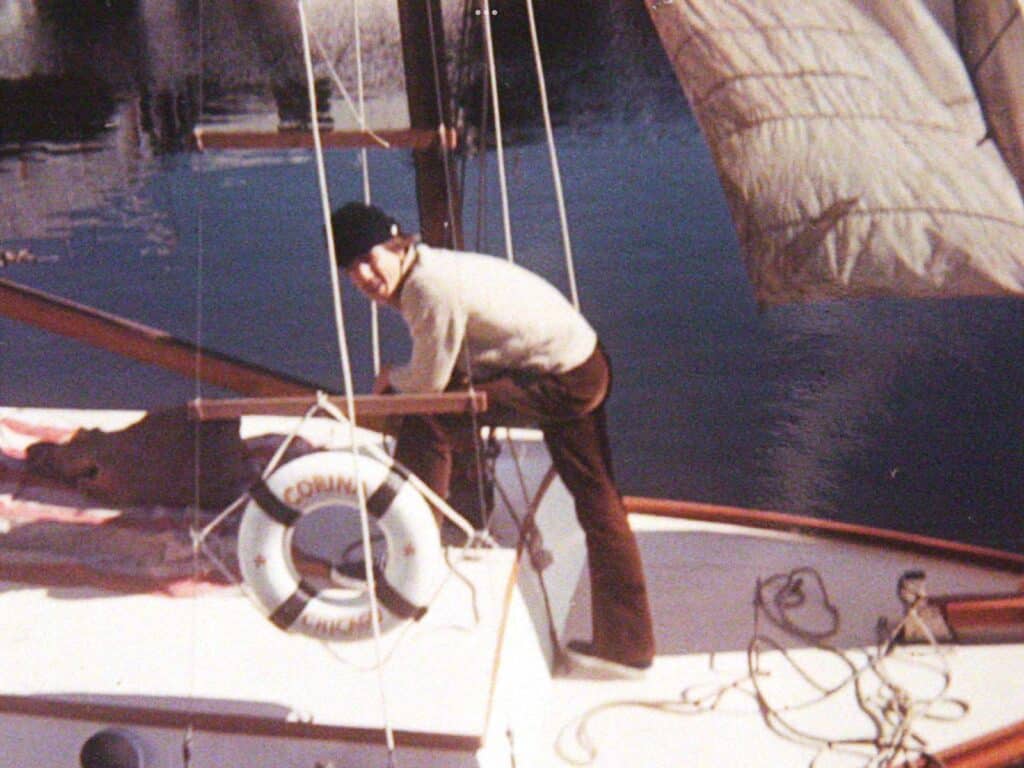

Worthless boats are worthless for a reason. Most have a major problem. My double-ender Corina lacked an engine and rig, and had been used as a hangout for illiterates. How do I know? They spray-painted the word “fock” inside the vessel. And they burned parts of the interior to stay warm. As a parting gesture, they defecated in the bilges. Best of all, the vessel was illegally tied up behind a factory on the north fork of the Chicago River and had to be moved ASAP.

Perfect. I paid $200 for the boat, lived aboard for four years, and extensively cruised the Great Lakes, Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico. I eventually sold that boat for eight times what I paid for it.

Wild Card, a Hurricane Hugo wreck, was awash on the beach at Leinster Bay, St. John, in the US Virgin Islands, with tropical fish swimming through the cracked hull. The National Park Service was demanding that the boat be immediately removed or they’d do it and bill the owner, an alcoholic ex-stockbroker who’d already fled to Vietnam.

Perfect. I paid him $3,000, smeared the hole in the port side with dried snot (aka fiberglass), and sailed the boat twice around the world over the course of 23 years (at an initial cost of 3 cents a mile). I then sold the boat for 10 times what I’d paid. The buyer was a male stripper who paid with sticky cash straight from his jockstrap.

My current vessel, a 43-foot Wauquiez named Ganesh, was originally listed for $140,000—which, once upon a time, it had been worth. However, over the course of four years, a hurricane had heeled this boat over in a storm trench, a tree had grown between the mast and forestay, the engine had frozen, and no one had bid a single penny toward a purchase for two solid years. And, within 30 days, the boat’s $6,000 annual yard bill and almost-as-expensive annual insurance were due.

Not perfect, but almost. I offered $40,000, saying, “Only one digit off, right?” We settled for $56,000 and left within the year for our third circumnavigation.

Amazing? Not really. I just found a worthless boat with a major problem and a ticking clock—and offered the desperate owner a last chance to get out from under its maintenance costs.

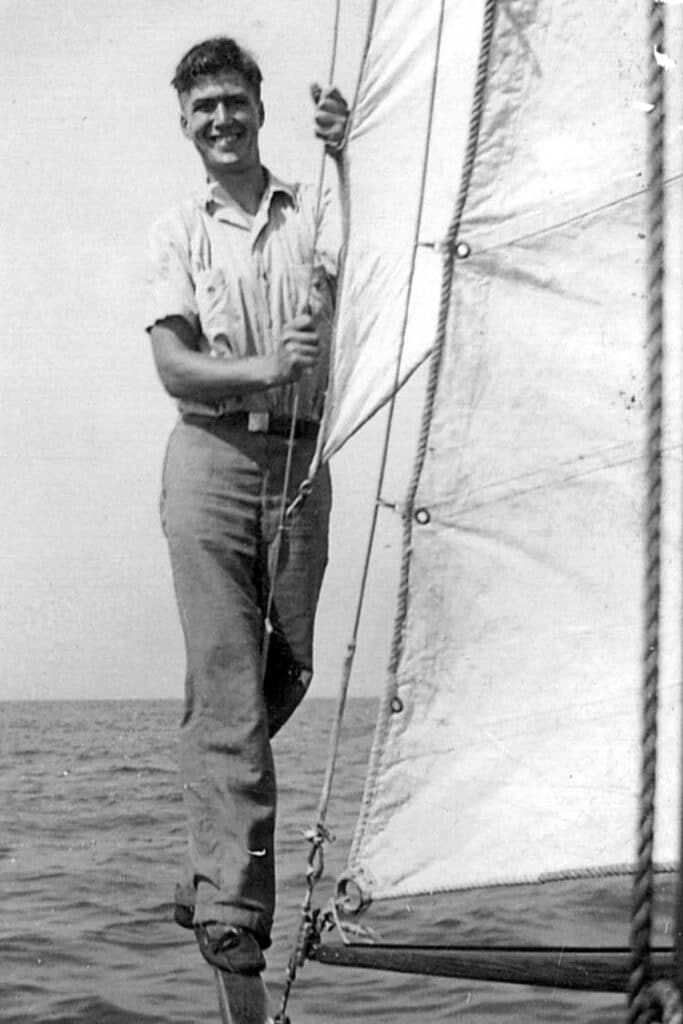

Why didn’t I mention my beloved 36-foot ketch Carlotta? Because I built that boat from scratch. The bare hull cost me only $600 in materials, back in 1971.

Anyone can do this if they’re handy, crazy, tenacious, and married to a masochist who finds fiberglass dust oddly pleasing.

Did I know how to rebuild a marine engine or design a rig or patch a hole with dried snot? Or shape a plank or caulk a garboard seam? Or replace a section of deadwood? Or calculate the crown of a deck beam? Or loft a life-size yacht?

No, of course not. But I searched out people who did know of such things, and I hugged them until they opened their hearts and told me their innermost construction secrets.

I simply refused to take no for an answer. When I couldn’t afford to rent a small garage to build my Ibold-designed Endurance 36, Carlotta, I formed a commune. We built six boats in a giant warehouse in Boston. Unable to afford to transport my 20,000-pound vessel, I (and a fella named Momo) built a flatbed trailer from scrounged scrap iron—which still might be transporting yachts around New England, for all I know.

At the time, the largest steam crane north of New York City was operated by a cigar-chomping guy who hated hippies—a fellow I had to set straight almost immediately upon meeting him. He said: “Don’t be silly. It costs over $20,000 for me to push the start button. Just the insurance rider alone costs…”

“You misunderstand me,” I shot back. “I have no money. I’m not here to hire you. I need you to launch me for free.”

You should have seen the look of disbelief and revulsion on his grizzled face. I went back every day for a week, every week for a month, and every month for a year—always with six-pack of beer, an herbally enhanced smile, and enough Zen to endure endless tirades against hippies, longhairs, and various other social parasites.

Finally, one day, he called me and barked: “Listen, you little turd. I’ve got a contract in Maine. After I go through the Fort Point Channel Bridge, I’m gonna have a problem with one of the engine gauges. Just to be on the safe side, I’m gonna put down my spuds to check it out. I’m only gonna be there for five or six minutes—so you’d best have your goofy Titanic all set to go along the seawall. Damn, I can’t believe I’m doing this.”

It’s amazing what you can do if you’re tenacious and stupid enough to ignore being told no a few thousand times.

A friend of mine named Eric lost the roof of his house and his Cape Dory Typhoon during Hurricane Hugo in 1989. His wife was hospitalized with stress. I felt bad for him. He was a good guy.

So, my wife Carolyn and I went around to all the restaurants on St. John and collected empty milk and water jugs—or, as I thought of them, micro lift bags. Next, I collected all the PFD devices on the island, plus all the yacht fenders for good measure. St. John has a lot of yachts, and the logistics of all this gear was pretty daunting.

I then purchased a can of fruit juice and a bottle of rum, and I announced a swim day in Cruz Bay. Dozens of folks showed up and swam with the empty jugs, as well as all the PFDs, down into the Cape Dory’s cabin. I encouraged them while lashing fenders from a loop of line encircling the keel. A dozen dinghies towed the awash vessel to the beach—where, at high tide, we hooked it to a Jeep and towed it into shallow water. When the tide dropped, we gravity-siphoned that boat, and then we hand-bailed the rest.

By nightfall, the boat was back on its mooring. Half the boats on St. John ended up with the wrong fenders afterward, but hey, that’s what happens when you mix good deeds and rum in the Caribbean.

Why relate this story? Because you can’t make sizable withdrawals without making massive deposits in the karma bank.

I learned this, and more, from my father. He was the type of sailor who, if you gave him a Popsicle stick and a Swiss Army knife, could whittle you up a handy little vessel in no time. His first boat cost $10. He paid $5 for the boat and $5 for the team of horses to haul it to his yard.

After coming back from World War II, he lusted after a lovely gold-plater that had just returned from a podium finish in the Newport Bermuda Race. It was a graceful, well-found John G. Alden (design No. 213, launched in 1924, sistership to Yvonne) schooner named Elizabeth. One day, the boat had a small fire in the gasoline-powered engine room and sank. Instead of shedding a tear at the demise of another classic American racing yacht, my father tossed a $100 bill in the air and dived into the muddy water of Illinois’ Calumet River.

Do you know what he said when he surfaced and called for the lift bags in the trunk of his car?

“Perfect.”

Fatty and Carolyn Goodlander are holed up at the Changi Sailing Club in Singapore, slowly replacing all their running rigging from their favorite international chandlery, Dumpster Marine. Their book How to Inexpensively and Safely Buy, Outfit & Sail a Small Vessel Around the World continues to make readers giggle.