Over forty years ago, when my husband and I embarked on our five-year sailing adventure to circumnavigate the globe, the world was a different place. I was a different person.

During ocean passages back then, we often saw swarms of flying fish and vast pods of dolphins that sometimes stretched from one horizon to the other. Coral reefs we explored were vibrant and home to a mind-boggling diversity of sea creatures. It was easy to find a good-sized fish to spear for dinner, and trolled lines usually scored a catch, even for fisher know-nothings like us.

Weather forecasts were rarely available, so when it came time to cross an ocean, we departed on a nice day, oblivious of what the weather gods might be brewing along our route. Our primary source of weather guidance was the compilations of weather logs tallied by decades of roaming seafarers: the wind roses displayed on ocean routing charts.

When we began that voyage in 1980, I had completed three years of college toward a career in dentistry, relegating my love of all things weather to hobby status. A meteorological profession just seemed too impractical and unorthodox. But after spending five years cruising—thwarted, propelled, battered, and enthralled by daily weather conditions—I realized that the atmosphere was my calling.

After the trip, I returned to school in 1985 to pursue a degree in meteorology with an emphasis on the Arctic. Why the inhospitable, cruising-unfriendly Arctic, you might ask? We had spent one summer exploring the high-latitudes north of Scandinavia: Norway, Svalbard, Jan Mayen Island and Iceland. Weather information was either non-existent or mostly useless, so I figured Arctic forecasting might be a worthwhile focus for my weather career. Plus, it’s an intriguing part of the globe that challenges scientific understanding with its complex interactions among winds, ice floes, ocean currents and harsh terrain.

While I was pursuing my meteorological studies at San Jose State University in the late 1980s, climate change was not yet widely recognized as a public crisis. That said, a few scientists had begun to ring warning bells about the effects of heat-trapping gases—the waste products from burning oil, coal and gas—on global temperatures and precipitation patterns. Even the fossil fuel companies acknowledged that burning their products would warm and disrupt the global climate.

It wasn’t until late in my journey toward a PhD in atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington that the collective groundswell of scientists’ anxiety surged about the destructive impacts of the changing climate. The Arctic in particular was already showing signs of the long-predicted, wholesale transformation of that region. Sea ice was disappearing, high-latitude temperatures were soaring, the Arctic system as we knew it was coming apart at the seams. Change was happening much faster and sooner than elsewhere on the globe. This blatant evidence of human-caused climate change spurred me to set my research sights on understanding how and why it was happening, as well as its impacts on other aspects of the climate system. Whenever and wherever we cruised, my antennae were tuned to detect changes, both expected and unexpected.

Fast forward to July 2009, we again set sail, but this time on a “family sabbatical year” of cruising with our two tweenagers. Saphira, an Atlantic 55 catamaran designed by Chris White, carried us on a circuit from New England to a summer in the Bras d’Or Lakes, then southward to Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, Colombia and Panama, followed by a northward turn up the east coast of Central America via Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, Yucatan, Key West, Bahamas and back home. Along the way I noticed many changes.

During our offshore passages, I wondered what happened to the large pods of dolphins and fleets of flying fish? While diving in Bermuda, it seemed the reefs were much less vibrant with life and color. Maybe it was due to hurricane damage, or, were rising ocean temperatures and pollution to blame? Some beaches in the BVI didn’t look anything like photos in cruising guides: once idyllic white sand was replaced by rocky shores. Beach sand does come and go with bouts of big swells, but the pervasiveness suggested erosion caused by sea-level rise could be at least partly responsible.

As we cruised through the San Blas Islands of Panama, my antennae picked up incontrovertible evidence of climate change. In several locations, our two-year-old charts indicated the existence of a small island. We found instead that the island had disappeared, replaced by a sand shoal completely submerged below the surface. While sea levels had risen only about 7 inches on average around the globe, the low-lying, unstable sand islets that make up the San Blas can be easily eroded even with only small changes in water height.

Elsewhere in the islands were obvious signs of substantial erosion, as roots of trees and shrubs were exposed along their shores, and many coconut palms had toppled into the sea. In the western islands at least, sea life seemed greatly depleted and many beaches were buried in plastic garbage transported by the trade winds from the east. The primitive homes of the indigenous Guna people perched inches above normal high water, and already they contended with regular flooding. Altogether, it was a disturbing scene. I wondered how many more years the Guna could inhabit these islands where they’ve lived for centuries.

That was 2009. More than a decade has passed, and my husband and I recently returned to the cruising life. Eight months a year we live on our new catamaran, another Chris White design also named Saphira. The pandemic prevented us from cruising to as many of the Caribbean islands as we had planned, but we have been able to return to the Bahamas, Virgin Islands, Lesser Antilles, Bonaire and Curacao.

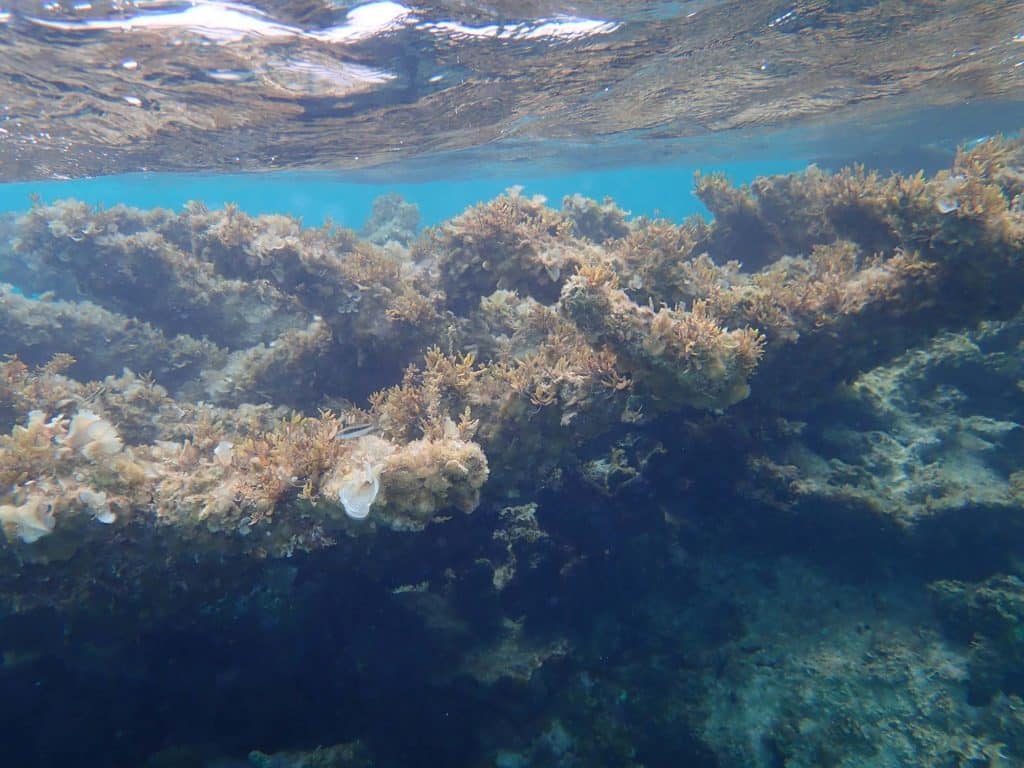

The news, I’m afraid, is even more disturbing. Coral reefs in the Virgin Islands, Bahamas, and northeast Caribbean islands (St. Martin, Antigua, Barbuda) have further declined. Most upsetting was our return to Conception Island in the Bahamas, a national park with no inhabitants or development. Back in 2010 we delighted in snorkeling around magnificent mushroom-shaped coral structures over 100 feet in diameter, seemingly growing out of a sea of perfect white sand in water so clear it was invisible. An astonishing variety of fish and sea creatures lived in the coral’s knobs and crevasses. Ten years later, in 2020, we returned to the very same coral mushrooms, excited for another chance to see these hives of sea life. But what we found instead were corpses; lifeless mounds of dead coral covered in a thick layer of brown algae. Only a few sergeant majors and barred jacks patrolled the area.

It was hard to hold back tears. I knew the earth’s coral reefs were struggling, but this blatant transformation from brimming life to utter death felt personal and terrifying. Because Conception Island had no development, it seemed unlikely that pollution could have destroyed these thriving colonies. According to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch program, the main culprits are rising ocean temperatures and disease, aided and abetted by overfishing.

The news is not all bad. Our southward heading brought us to Bonaire and Curacao, where the corals are still healthy and teaming with life. Cruising friends report healthy reefs in parts of the Windward Islands, as well. These relatively healthy reef systems, along with local efforts to grow new coral colonies, can help restore this vital ecosystem, but only if we give them a chance. Further warming caused by emissions of heat-trapping gases produced mainly by burning fossil fuels must decline dramatically and rapidly, or else cruisers will encounter more and worsening impacts of these gases.

Not only are oceans warming, but they are also becoming more acidic as they absorb carbon dioxide from the air, which is converted to carbonic acid in salt water. Higher acidity stresses marine creatures that form hard shells from dissolved calcium carbonate, such as corals and mollusks. Climate scientists like myself have known for many decades that increased greenhouse gases would have these impacts, and we’re now learning about the many ways that a warmer earth will cause stronger storms and more frequent extreme weather events of many kinds. Recent Atlantic hurricane seasons have shown us a glimpse of the future, with higher numbers of major tropical storms, more cases of rapid intensification, and heavier rainfall when they come ashore.

We cruisers are acutely attuned to our surroundings, from weather and sea state to currents and marine life. We are also on the front lines of the impacts of a changing climate. As my husband and I continue to explore the planet by boat, I expect to see ever-clearer evidence of the monumental changes resulting from human activities to date. My research will continue to focus on uncovering details of why these changes occur and which regions will be affected.

Governments, businesses, and individuals can (and must) work together to reduce carbon emissions, curtail overfishing, prohibit harmful coastal development, and restore devastated marine life. The cruising community can help by getting the word out, volunteering in local efforts to repair and prevent damage, advocating for action, and minimizing our own impacts on the beautiful coasts we are so fortunate to visit.

Jennifer Francis is acting deputy director and senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Mass.