In the past 50 years, the cruising scene has undergone major changes in boat design, performance, building material, electronic equipment, aids to navigation, and communications, as well as greatly improved weather forecasts. Jimmy Cornell has witnessed all these changes on his five Aventura boats, the first launched 50 years ago in July 1974. We asked him which changes he considers to be the most significant.

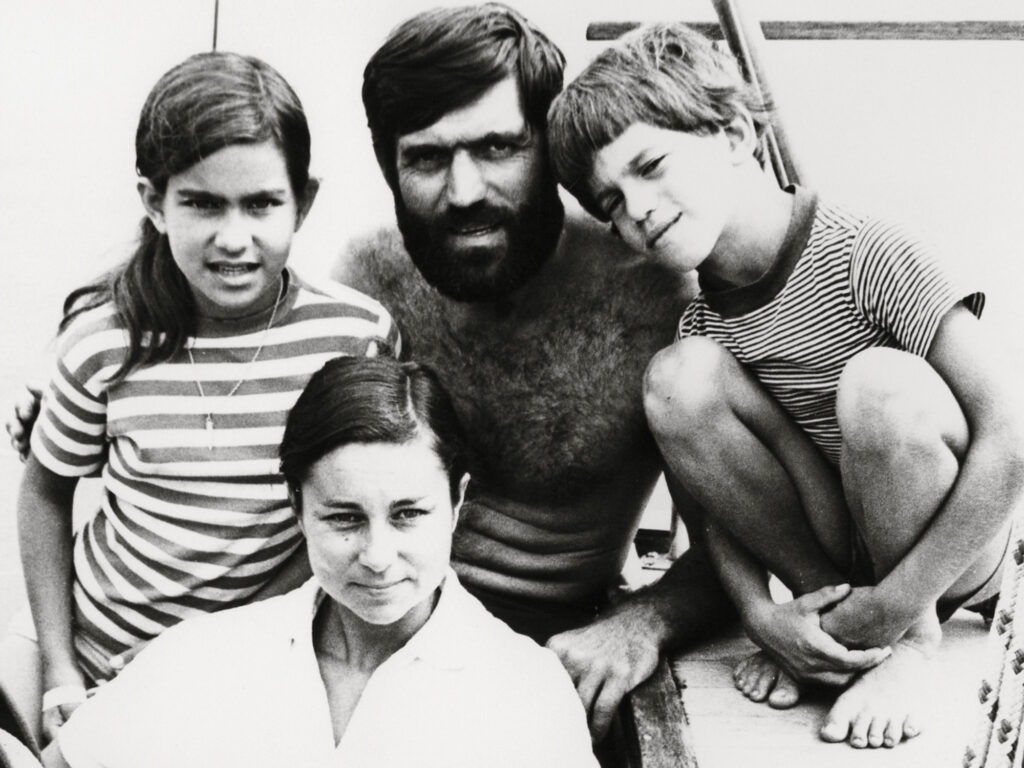

No aspect of long-distance cruising has seen a greater improvement than safety. I still shudder when I remember the sleepless nights and constant worry about the safety of my family during our world voyage from 1975 to 1981. I doubt that anyone used to satellite navigation can imagine the anguish of sailing through areas of known dangers using systems that had little changed since the days of Capt. Cook.

We reached the Pacific Ocean via the Panama Canal in late 1976. Then, rather than take the traditional route to French Polynesia via the Galapagos Islands, we detoured to Peru to visit the home country of Paddington Bear, my children’s much-loved fictional character. This detour morphed into a daredevil land expedition that took us from the Inca vestiges in the High Andes to the carnival in Rio de Janeiro to the Iguazu waterfalls in Argentina. Back on Aventura, we sailed to Easter Island, Pitcairn and Mangareva in the Gambier Islands.

From there, our passage to Tahiti had a complication. In those days, France was conducting nuclear tests on the Mururoa and Fangataufa atolls, and we had to obtain permission from the French authorities for the passage to Tahiti. I was alarmed to see that the allowed route had to clear the prohibited area by 50 miles.

It cut across the southern Tuamotus and past the uninhabited atolls of Maria, Tureia and Vanavana, in an area aptly called “the dangerous archipelago.” No deviation was allowed. We simply had no choice.

Maria is 90 miles from Mangareva, so we left late in the day. We planned to sail during the night in open waters and pass the atoll in daylight.

At daybreak, I was shocked to see Maria’s low profile peeping over the horizon several miles behind us. We had gained some 20 miles on our estimated position, driven by a swift northwest-setting current. It was 150 miles from our current position to Tureia, and 30 more miles to Vanavana.

At that point, my astronavigation had become reasonably accurate. When the conditions were right, I was able to work out our estimated position within 5 miles of our actual location. However, a single sight allowed for only a position line to be drawn on a chart, with the location of the observer being anywhere on that line. Therefore, a second sight had to be taken later, so the actual location would be at the intersection of the two plotted lines.

The easiest way to obtain an accurate position was to take a noon sight about five minutes before the sun reached its highest point above the observer (meridian passage), and then take a second one five minutes later.

We didn’t have an accurate timepiece on board, so whenever I took a sextant sight, I started my stopwatch. I then switched on our short-wave radio receiver and tuned in to the WWV station frequency, which regularly broadcast the hour and minute in Coordinated Universal Time.

Throughout the day, I kept taking sights. By nightfall, I reckoned we had some 100 miles of open water ahead of us. This gave us a safety margin of about 90 miles, after allowing for an estimated 2.5-knot current at a speed of 5 knots through the water.

My main concern was that, pushed by a strong current, we could easily cover that distance in the 12 hours of darkness.

At such times, we depended entirely on classic dead-reckoning navigation. Every hour, I wrote down in the logbook the course steered and the distance covered. The latter was based on the readings provided by the trailing log. This consisted of a four-blade propeller attached by a long line to a counter fixed on the stern of the boat. The counter indicated our speed through the water, which allowed me to calculate our estimated speed and the distance traveled since the previous reading.

During the squally night, the overcast sky made it impossible to take any star sights, so I tried to slow down by reducing sail, but in the 20- to 25-knot wind, it didn’t make much difference. I spent a gut-wrenching night peering blindly ahead into the darkness and listening for the boom of the swell breaking on a windward reef.

Just as dawn started lightening the eastern horizon, I glimpsed straight ahead of us, at less than half a mile, the telltale white line of breakers. Tureia.

I disengaged the self-steering gear, altered course to port, and steered Aventura at a safe distance off the southern edge of the atoll. It looked much smaller than I expected, but I thought it might be an optical illusion. A couple of hours later, when the sun was high enough to take a sight, I managed to work out our approximate position.

It was a shock to realize that the atoll we had just passed had, in fact, been Vanavana. The much-stronger current than I’d anticipated had pushed us much farther west. We had passed Tureia in the dark without seeing it, a discrepancy in my estimation of some 40 miles.

Another 10 minutes of darkness, and we would have been wrecked on Vanavana’s windward reef. Even now, with the benefit of hindsight and much better charts, I find it impossible to believe that we covered so much ground during the night, unless we had been driven by a 4-knot current.

We reached Tahiti without any further excitement and spent a delightful time exploring the picturesque Society Islands. Then we enjoyed a leisurely cruise through the Cooks and Tonga. By the time we reached Fiji, the anchorage off its capital, Suva, was full of cruising boats preparing to sail south to spend cyclone season in New Zealand. The motley collection left me wondering where all those yachts advertised in glossy magazines and exhibited at boat shows were. Certainly not there.

Still, it was an opportunity to find out more about boaters’ views on essential aspects of cruising. I prepared a questionnaire and visited the boats in my dinghy. Only boats that had been cruising for at least three months were included. Most had been sailing much longer. Three were completing a circumnavigation, and one was on its second. The average length of their current voyage was 2.6 years, and the average miles sailed was 14,800. With an average sailing experience of 13.8 years, their observations gave considerable authority to the survey results.

There was, however, one aspect that I found surprising: watchkeeping. By their own admission, 17 skippers kept no regular watches. The crew went to sleep on ocean passages and kept only “loose” watches at other times.

This relaxed attitude probably explained why only 40 boats had an inflatable life raft. The remaining owners claimed to have other arrangements prepared in case of an emergency: Ten planned to use their inflatable dinghy, of which seven were kept permanently inflated on passage, and three were fitted with carbon-dioxide bottles for rapid inflation. A further eight intended to use their hard tender, three of which were fitted with mast and sail. The remaining four told me that they had no intention of abandoning their boat.

Unfortunately, in those pre-GPS days, boat losses were a regular occurrence in the South Pacific. Looking back, I can only describe our willingness to accept such risks as fatalism: If something is going to happen, it will happen anyway. If you wanted to explore the world, then you had to be prepared to take risks, and most of us did.

In a follow-up survey, I investigated 30 cases that resulted in 23 total losses and eight near losses. Among the former, five boats and their crew disappeared while on passage. Three of those tragedies happened during a cyclone. The cause of the other two is unknown. A further two boats were lost after collisions with unidentified objects at night, but their crew managed to save themselves. This was also the case of the two boats that were lost after colliding with whales.

The crews of three boats that were lost when they ran aground on a reef at night also survived, as did those of the three boats that broke up when their boats were driven ashore during cyclones. The crew survived in all other losses or near losses.

Keeping In Touch

Offshore communication has also enormously improved the safety and enjoyment of long-distance cruising in the past half-century.

My first Aventura did not even have a VHF radio. During our 28-day transatlantic passage in 1976, we had no means of communicating with our family other than sending a telegram after landfall.

Among the 62 boats in the South Pacific survey, half had long-range radios (23 had ham radios and eight had single-sideband sets). The other half, mostly the non-American ones, had no radio transceivers, except a few who had VHF radios. In those days, ham radios were the only practical answer for offshore communications because marine single-sideband sets were prohibitively expensive.

Email didn’t exist, and receiving and forwarding ordinary mail caused more headaches than anything else. General delivery was the most used receiving address, but it was also possible to have mail sent to the address of the local port captain, a local bank or an American Express agency.

Arranging an international bank transfer was often a real nightmare too. Nearly half the participants in the South Pacific survey (30) carried all their money in cash.

If something is going to happen, it will happen anyway. If you wanted to explore the world, then you had to be prepared to take risks, and most of us did.

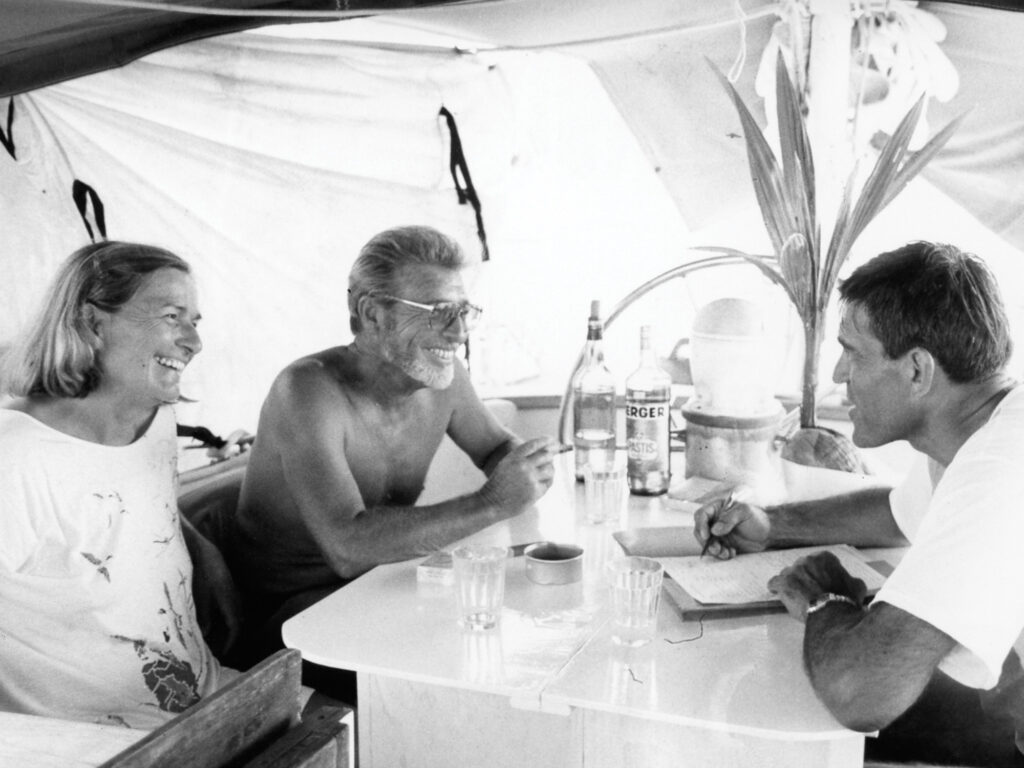

While some of the findings of that early survey might no longer be of much interest, some subjects are still relevant. So I did another survey. I interviewed 65 sailors who had completed a world voyage or were preparing to leave on one soon. Among them, 26 had completed at least one circumnavigation and a further 18 were close to closing the loop.

One aspect that has dramatically changed over the years is the average length of cruising boats. The 65 boats in the new survey had an average length of 49.1 feet, a considerable increase from the average length of 39.2 feet in the South Pacific survey.

Two other significant changes are rigs and hull material. In the South Pacific survey, half the boats (31) were one-masted, among which 19 were sloops and 12 were cutters. Among the two-masted boats, 27 were ketches, three were schooners, and one was a yawl.

And now? Among the 65 boats in the new survey, there was only one ketch. All the others were one-masted, the majority having some kind of two-foresail arrangement, although few could be described as proper cutters.

As for hull material, in the South Pacific survey, 33 boats had a fiberglass hull, 15 were wood, five were steel, four were plywood, four were ferro-cement, and one was aluminum. In the new survey, 26 boats were FRP, 17 were composite, 17 were aluminum, three were steel, and two were plywood.

Not surprisingly, monohulls were the vast majority (57) in the South Pacific survey, with five trimarans and zero catamarans. Monohulls continue to be in the majority today, with 43 among the boats in the new survey, along with 21 catamarans and one trimaran.

Consumption and generation of electricity are also notable. In the South Pacific survey, 48 boats used their main engine as the primary source of generation, 12 had a diesel generator, 15 had a portable gasoline generator, two had a towing generator, and two had solar panels.

Today, only two boats in the new survey relied entirely on their engine for generating electricity, while 11 owners—who described their engines as their primary source of generation—also used other means. Solar panels were the primary means of generation on 22 boats, with 15 among them obtaining more than 80 percent of their electricity from that source. A total of 37 boats were equipped with diesel generators, but they were the primary source of generation on only seven boats. The number of hydrogenerators was surprisingly small, but the 14 owners who had them were pleased with their performance. Even lower was the number of wind generators, at 11, which is probably explained by their poor performance when sailing downwind.

By comparison, in the South Pacific survey, only four boats were using renewable sources of energy, whereas 54 of the 65 boats in the new survey produced more than half (52 percent) of their electricity needs from solar power. An additional 14 percent was produced by hydro and wind power. That’s what I call progress.

One area where the South Pacific predecessors were far ahead of the current generation was the extensive use of wind-operated self-steering gears. Among the 62 boats in the South Pacific survey, 42 had wind self-steering gear, 28 had an autopilot, 14 had both, and six had neither. In the new survey, 16 boats had a wind self-steering gear and all had an autopilot, with several having a second autopilot as a backup.

Communications

In the new survey, all boats had some kind of satellite communications on board. More than half used Iridium Go! and PredictWind forecasts. Among those who wanted instant voice-communication capability, the Iridium satphone was preferred, as it also allowed for less-expensive text messages to be sent or received. The days of SSB radio seem to be numbered; there were only three boats that had this useful and virtually free means of communications—for both voice and email.

The arrival of Starlink and its instant popularity among cruising sailors may herald the most significant development on the world cruising scene since GPS. The completion of my latest round-the-world rally, the World Odyssey 500, in late June gave me an opportunity to interview the 10 finishing crews about their three-year circumnavigations. With one exception, all had upgraded to Starlink as soon as it became available. They were all ecstatic about the contribution that Starlink had made to the enjoyment and safety of their voyages.

I was also curious about the kind of receptions they had received from local people along the rally route. The sailors said they were warmly welcomed everywhere, and many admitted that interactions were better than expected, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. In most places, the locals were pleased to welcome cruising boats again.

It makes me very happy to say that, at least in that respect, nothing about cruising has changed.