For the past 30 years, Andrew Burton has been trying to put himself out of a job—because he doesn’t want owners of the boats to miss out.

“A lot of delivery skippers won’t have the owner on board,” he says. “I encourage it, because for me, the fun part is the offshore sailing. To take that away from the owner doesn’t seem right.”

He wasn’t always so concerned about sharing his biggest joy. He can remember, long ago, listening to a single-sideband radio to check in with other captains.

“Six o’clock every day, we’d catch up with weather and see where everybody was,” he says. “And every now and again, we’d hear the Coast Guard in a conversation with somebody abandoning the boat. I was young and not particularly empathetic: ‘These idiots, going out there with no experience.’”

He shakes his head and adds, “As I matured, I started thinking about why those people were getting off their boats, usually giving up on a lifetime dream of sailing to the Caribbean.”

Many folks just weren’t prepared for the reality of offshore sailing, he realized.

“They get out there, and it’s blowing 35, and the motion is something they’ve never experienced because there can be three different components to the waves,” he says. “They’re wet, exhausted, scared, the decks are leaking, it’s the middle of the night, and they’re seasick. So it seems like the best thing they could possibly do is call the Coast Guard.”

Finally, Burton decided that he could help people learn to sail safely offshore—and maybe even find their own bluewater joy.

An Idea Emerges

in the 1990s, nautor swan managed a fleet of midsize and larger charter sailboats that migrated between summers in Rhode Island and winters in the Caribbean. Burton did a lot of those deliveries.

“I worked out a deal where I chartered the boats and put paying crew on them, to help them learn,” he says. “For many, it was their first time out of sight of land or sailing at night.”

That’s how Adventure Sailing was born. It’s Burton’s company, which teaches sailors how to enjoy, rather than simply endure, their time at sea.

All of Burton’s clients must have basic sailing knowledge and know how to steer a compass course. If not, he suggests they first get educated at a place such as J/World Performance Sailing School. “Tell them what you want to learn, then come back, and we’ll go,” he says.

Instead of asking for references, he has blunt conversations about experience and fitness: “I tell them, ‘If you bullsh-t me, it’ll be a waste of money. But if what you’re telling me is true, well, then, this is a really good value, and you’ll get a lot out of it.’”

“They get out there, and it’s blowing 35. They’re wet, exhausted, scared, the decks are leaking, it’s the middle of the night, and they’re seasick. So it seems like the best thing they could possibly do is call the Coast Guard.”

Typical clients own a small cruising boat and are hoping to step up to one that’s bluewater-capable. Burton has two basic goals: “One, to help people realize their dream of going offshore by providing the tools to do it successfully. And two, to give them a good baseline in what offshore sailing is all about.”

His most successful passages have a convivial crew, and most have never met before they sign up.

“If somebody sounds like an idiot,” he says, “well, then, I’m sorry, but we’re full.”

Building the Business

Nautor Swan sold its charter fleet several decades ago, but on one of the last trips, Burton had nine boats leaving Newport, Rhode Island, with 54 people headed offshore. By then, his reputation had built a word-of-mouth private client base.

By fall 2017, Burton and his wife, Tami, had spotted a Baltic 47 for sale. The boat needed new teak decks and an electronics upgrade, but it had what he calls “three really good” cabins, plus one for himself. The layout was perfect for Adventure Sailing.

“Generally, it’s myself and six paying people,” Burton says, of Masquerade, adding that he encourages couples to sign up together. “We run three watches, with somebody new coming on every hour and a half, so everybody gets to know each other.”

With six hours off, there’s plenty of time for relaxation. All of his clients have to steer, he says, “because that’s how you get the feel—to really know a boat. Unless we’re motoring, the autopilot stays off. We talk about storm tactics, weather, all kinds of things, but it’s not constant teaching.”

For instance, he sits in the cockpit and tells sea stories and answers questions—lots of questions— because the whole point is to get the experience of being out there.

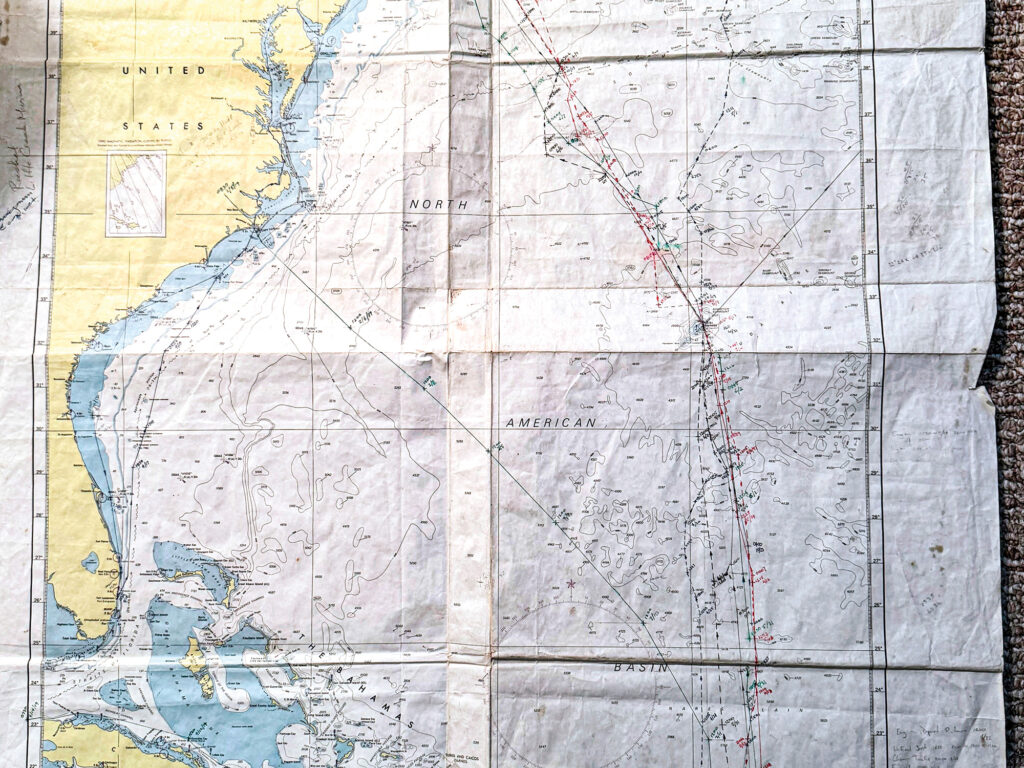

Burton also does the cooking, and says he really enjoys it—though he has an ulterior motive. Before GPS, he’d get out of dishwashing duty by charting the day’s course. Now that crewmembers can pinpoint the boat’s exact location themselves, cooking has become his escape. “GPS took a lot of the fun out of it, but it’s also allowed more people to get out there and do what I love to do,” he says.

Most clients eventually go offshore on their own, but not all. He’s had some customers step off the boat in Bermuda and buy a plane ticket home. “They’d say, ‘Hey, Andy, I really hated it,’” he recalls. “And: ‘Thank you very much. You just saved me a lot of money.’ I get it—there can be a lot to hate about offshore sailing.”

With some clients, he’ll offer a challenge: He takes them to the Caribbean, and then they have to bring the boat back on their own. Shipping is a good option for some boats, he says, but he estimates that delivering a boat on its own bottom costs about half as much. “And if you’ve got a good skipper, there’s not going to be that much wear and tear,” he adds. “Anybody worth his salt is gonna take really good care of the boat.”

Over the Horizon

As we chat, Burton is waiting for a weather window to ease his next delivery to the Virgin Islands. Forecasting has gotten better during the past 30 years, but even the best forecaster can get it wrong. On one delivery from Bermuda back home to Rhode Island, Burton decided to heave-to rather than bash upwind into a strong northwesterly blow. He was settled in under the dodger, admiring the huge whitecapped swells and “that gorgeous turquoise, when you look through the top of the wave,” when another boat passed by close enough to chat on the VHF radio.

“They asked if we were all right,” he says. “I told them we were just having a cup of tea.”

By the next morning, the wind had shifted southwest, so they set sail again—and soon passed that same boat, which was by then hove-to, with no one on deck.

“Our goal is to be inclusive. The idea is for all the owners to have the same thrill that I did finishing my first Bermuda race as skipper, because that thrill was still there finishing my second race.”

“They must’ve gotten just over the horizon and decided, ‘Yeah, that doesn’t sound like a bad idea,’” he says.“One of the things that I teach people is how to heave-to, because if everything hits the fan, you can stop and wait for it to go away.”

In 2018, Burton entered Masquerade in the Newport Bermuda Race. He’d delivered boats to the island hundreds of times before, but says they finished in “the cheap seats.” In 2022, Masquerade won its class and finished second in the cruising division. As he prepares for this year’s race, he’s also trying to help organizers streamline the entry process.

“Our goal is to be inclusive,” he says. “The idea is for all the owners to have the same thrill that I did finishing my first Bermuda race as skipper, because that thrill was still there finishing my second race.”

Adventure Sailing is currently booking clients for 2025, and for Burton’s eighth and ninth trans-Atlantic crossings: to the Azores and Scotland in June and back to the Caribbean in the fall. Add in five Panama Canal transits and 40 years of multiple deliveries between the East Coast and the Caribbean, and it’s easy to believe his personal sailing estimate of close to 500,000 miles logged.

Along the way, he’s helped many sailors achieve their dreams—all without accumulating many dramatic sea stories.

“Boats give us so much pleasure, especially one like Masquerade that’s such a delight to sail,” he says. “I have such mixed feelings about making landfall. On one hand, we’re happy to be reaching the goal and looking forward to a celebratory beer. On the other, we know we’re really going to miss sailing offshore.”