In 1974, Australian journalist Murray Davis assembled a ragtag crew of sailors and scribblers in Newport, Rhode Island, and put out the first issue of Cruising World. The bet Murray made that summer was a big one: 65,000 big ones, if bets are measured in printed magazine copies. Ten years later, he sold the brand to The New York Times Company. Paid circulation had grown to 120,000 copies addressed to high-net-worth individuals (in the parlance of Madison Avenue). Davis retired to a life of ease on Newport’s tony Ocean Drive.

In some ways, the joke was on Madison Avenue. Davis’ genius was to tap into a countercultural zeitgeist impelled by skyrocketing oil prices, back-to-the-garden dreams of self-reliance evinced by the Whole Earth Catalog, and a particularly prominent June 1973 Time magazine story called “The Good Life Afloat,” which placed, of all boats, a Westsail 32 front and center.

“Beached though he may be by responsibilities ashore,” the Time story went, “the cruising sailor can still feel a certain smugness about his boat. She can take him across an ocean whenever he is ready to go. Just a few years ago, the men who owned boats like these were usually looked upon as oddballs, dropouts, or dreamers ready to up-anchor and take off for the islands. They were incurable eccentrics, antiquarians putting in their time refurbishing relics of another age. But suddenly those old-fashioned boats and their gear seem strangely up-to-date. The cruising sailor seems less eccentric. The boats they have preserved have now become objects of envy.”

Playboy magazine took the idolatry a step further in a 1976 feature: “Your ultimate destination in a Cigarette boat may be no farther than the forward berth, but there is no navigable place in the world beyond the range of the Westsail 32.”

Davis came to the subject honestly. For the first half of the 1960s, he’d written a column about the Western Australian waterfront scene for The Age, a Melbourne daily. That lasted till his wanderlust overtook him. In 1967, he and his wife, Barbara, and their two small children boarded a 21-ton, yawl-rigged Falmouth Quay punt called Klang II and sailed themselves to America.

“Every escapade needs a hook to lend it legitimacy,” Nim Marsh wrote in a 2004 profile. Davis’ hook was, in his own words, “to watch Australia’s challenge for the great symbol of sailing, the America’s Cup.” He would cover the races in Newport, in which Australian hero Dame Pattie was to compete, reporting back to his readers in Melbourne. As the Davis family sailed halfway around the world, they befriended some of that era’s giants of the cruising community—Eric and Susan Hiscock, Miles and Beryl Smeeton, Blondie Hasler—as well as young up-and-comers such as Lin and Larry Pardey and Bruce Bingham. The first issue of CW included dispatches from all of them.

Though Davis tapped into a deep vein, he didn’t invent the worldwide cruising community; instead, he discovered one that by the 1970s was already thriving. To locate the father of this community, he’d have to look back still another 50 years to a man named William Washburn Nutting—arguably the most influential cruising sailor that today’s cruisers have never heard of.

We All Sail in the Track of Typhoon

“I think it is reasonable to say that a country is only as big as its sports. In this day when life is so very easy and safe-and-sane and highly specialized and steam-heated, we need sports that are big and raw and, yes, dangerous. Not that we recommend taking chances in the roaring forties in the middle of November or crossing the Atlantic on the fiftieth parallel at any time of the year. This sort of yachting, I suppose, will never be popular. But I do hope that if there is any result from my book on the Typhoon, it will be to inspire a confidence in the possibilities of the small yacht and instill an interest in the sea and a desire to explore.”

Thus wrote W.W. Nutting. His 1921 book, The Track Of The “typhoon,” lit a fire whose flame still spreads more than a century later. “I feel that what American yachting needs is less common sense, less restrictions, less slide rules, and more sailing,” Nutting wrote.

A line he borrowed from a US Navy sub-chaser commander distilled Nutting’s ultimate disdain for his own safe-and-sane era: “Is ‘Safety First’ going to be our national motto?”

Like Davis, Nutting started his career scribbling on the waterfront scene—in Nutting’s case, from the Manhattan offices of The Motor Boating Magazine in the years just before World War I. Nutting was a gregarious man who gathered around him a Parisian-style salon of other men who were interested in something entirely new under the sun: sailing on the ocean “for the fun of the thing.”

In the 1910s, there was no seagoing cruising community. Yacht clubs had begun to proliferate after the Civil War, but with a focus that seldom extended beyond inshore racing. A handful of America’s wealthiest Brahmins very occasionally raced to Bermuda or across the Atlantic, but with large crews of paid professional sailors. Amateur sailors had made well-publicized ocean voyages: Joshua Slocum, who published his enduring bestseller about the first recorded solo circumnavigation from 1895 to 1898; Howard Blackburn, who in 1901 crossed to Portugal in 39 days aboard a 25-foot Friendship sloop. Still, before World War I, there was neither a cohort of long-distance cruising sailors nor a fleet of seaworthy yachts to take them sailing.

Nutting changed that. In summer 1913, with scant experience of sailing, piloting or navigation, he sailed the 28-foot cutter Nereis, mostly singlehanded, from New York to Newfoundland. Along the way, he survived several near calamities. Off Nantucket, Massachusetts, he was knocked overboard by the boom. Only dumb bloody luck and a loose lazy jack saved him from drowning. But that summer’s experience inflamed his adventuring spirit, and the stories he published inflamed others. With friends he met during those travels, Nutting began to dream of a shorthanded trans-Atlantic voyage—and of the boat that could accomplish such a trip.

One of those friends was Canadian engineer Frederick W. “Casey” Baldwin, the first British subject to take flight in March 1908, shortly after the Wright Brothers’ first Kitty Hawk flights, and the man who would go on in 1919 to set the world speed record of more than 70 mph across the water in a hydroplane that he designed and built with Alexander Graham Bell.

Though World War I interrupted the conversation they had started in 1913, Nutting and Baldwin reconvened in fall 1919 to work out their plans—for the boat and for the voyage. Nutting wrote: “Finally we got down to the inevitable subject of boats and more particularly of cruising boats.”

Their choices were limited to one of two categories: fishermen or racers. There simply were no other choices. Fishermen—adaptations of Friendship sloops, oyster dredgers or Gloucester schooners—accounted for all the boats sailed in shorthanded transoceanic voyages. These tended to be rough-hewn, solid, seaworthy and slow. Casey, by contrast, had collected silver by racing lightly built boats with long overhangs designed under Nathanael Herreshoff’s Universal Rule. Casey, Nutting wrote, was “all for a big boat—as big a one as possible without going beyond the strength of one man in the matter of the mainsail and the ground tackle, which are really the limiting factors.”

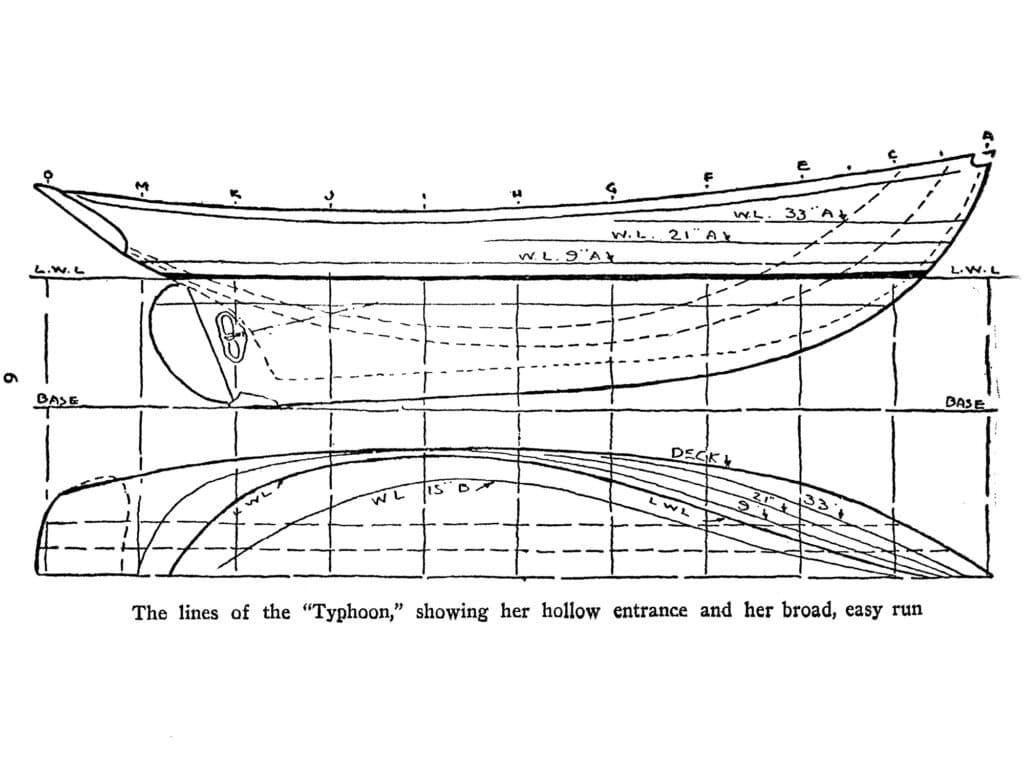

Nutting’s tastes were shaped by his summer on Nereis. “I think a singlehander should be as small as possible without sacrificing full headroom—say, 28 to 30 feet on deck,” he wrote. But, conceding that singlehanding wasn’t the most desirable way to cruise, he consented to a compromise: “a 40-footer, fisherman style, ketch rigged with an auxiliary motor.”

Ocean Sailing “For the Fun of the Thing”

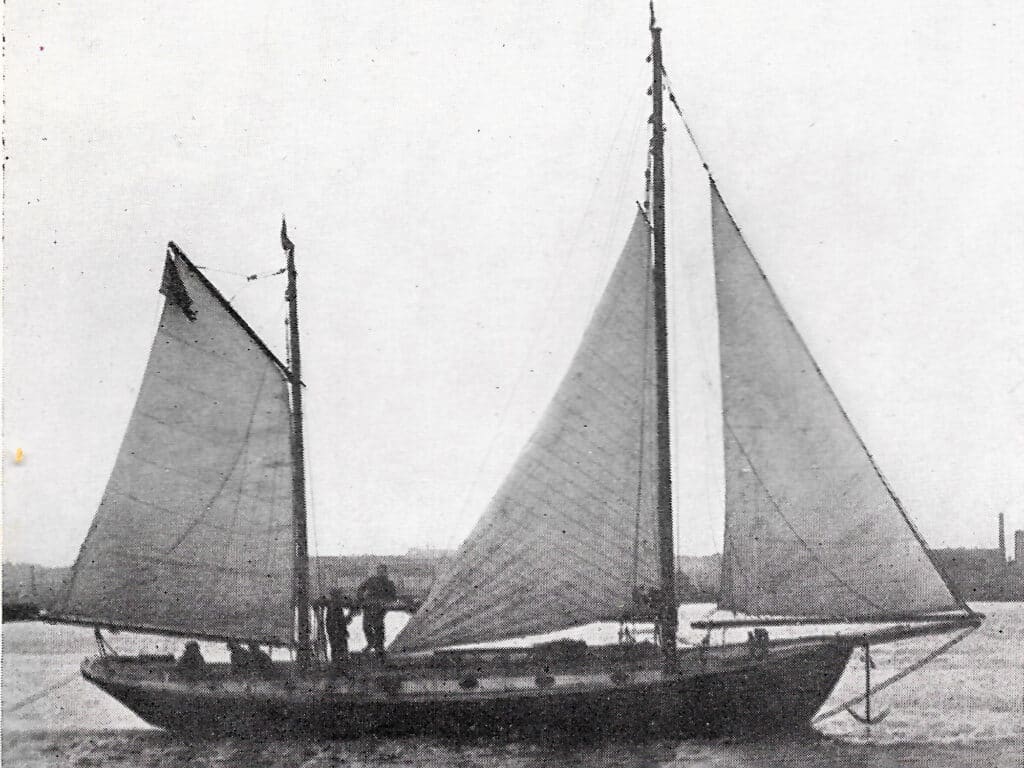

Back in New York, Nutting delivered his commission to yacht designer William Atkin, a pal and stablemate at Motor Boating, who pushed the length to 45 feet before the boat was done. Baldwin oversaw the boatbuilding at Bell’s laboratory in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, and on July 3, 1920, Typhoon launched.

As Davis legitimized his escapade with the hook of an America’s Cup summer, so Nutting latched onto the Harmsworth Trophy Races, set for August 10 in Cowes, England, to legitimize his. “Not that there was any serious motive behind the cruise of the Typhoon,” Nutting hedged. “We were not trying to demonstrate anything; we were not conducting an advertising campaign; we hadn’t lost a bet. I had the little vessel built according to Atkin’s and my own ideas of what a seagoing yacht should be, and we sailed her across the Atlantic and back again for the fun of the thing. We feel that the sport of picking your way across great stretches of water, by your own (newly acquired) skill with a sextant, pitting your wits against the big, more or less honest forces of nature, feeling your way with leadline through fog and darkness into strange places which the travelers of trodden paths never experience, chumming with the people of the sea—these things, we believe, are worth the time, the cost, the energy—yes, and even the risk and hardship that are bound to be a part of such an undertaking. We did it for the fun of the thing, and we believe that no further explanation is necessary.”

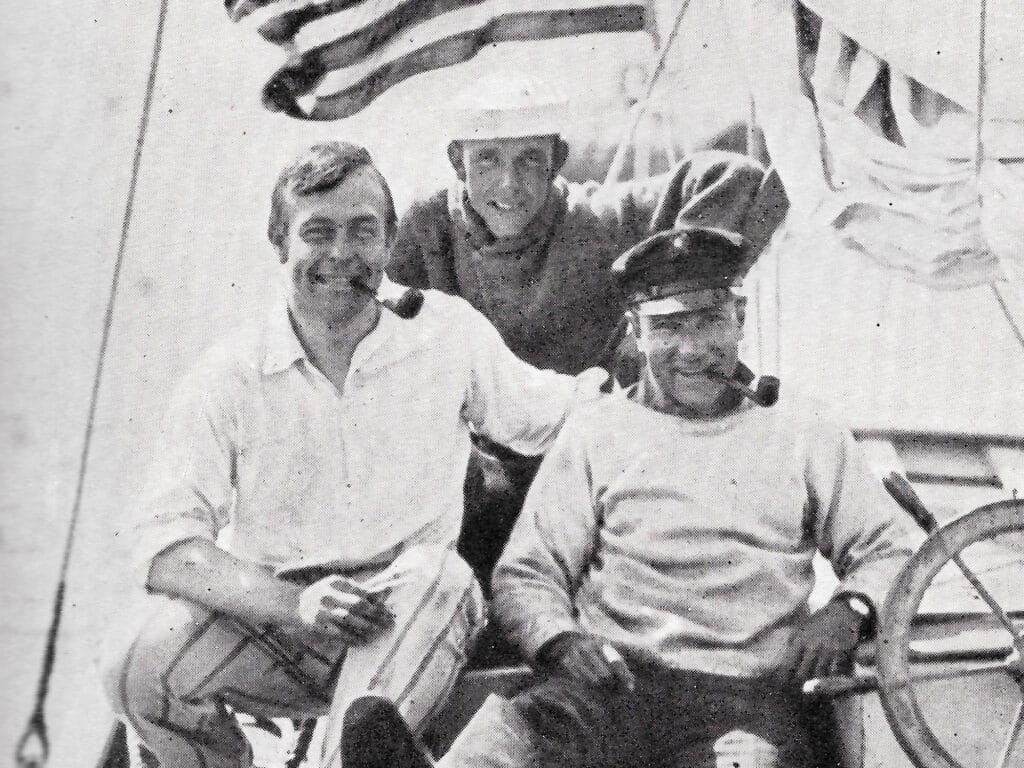

They did it, all right, crossing from Baddeck to Cowes, 2,777 miles in just over 22 days. Along the way, they encountered several gales, which Nutting illuminated for his steam-heated readers in full, breathless detail: “It was a roaring, wild, wonderful night, the sky pitch black, the sea a driving stampede of weird, unearthly lights. The countless crests of breaking waves made luminous patches in the blackness as though lit by some ghostly light from beneath the sea, and the tops, whipped off by the wind, cut the sky with horizontal streaks of a more brilliant light, like the sparks from a prairie fire.”

For a shipmate, Nutting could have picked no one better than Baldwin. “Casey, drenched and grinning, was in his element,” he wrote. “The wind was still increasing, but there was no trace of concern in his voice as he shouted back a ‘cheerio’ through the racket. He was enjoying himself as only the man at the wheel can at such a time.”

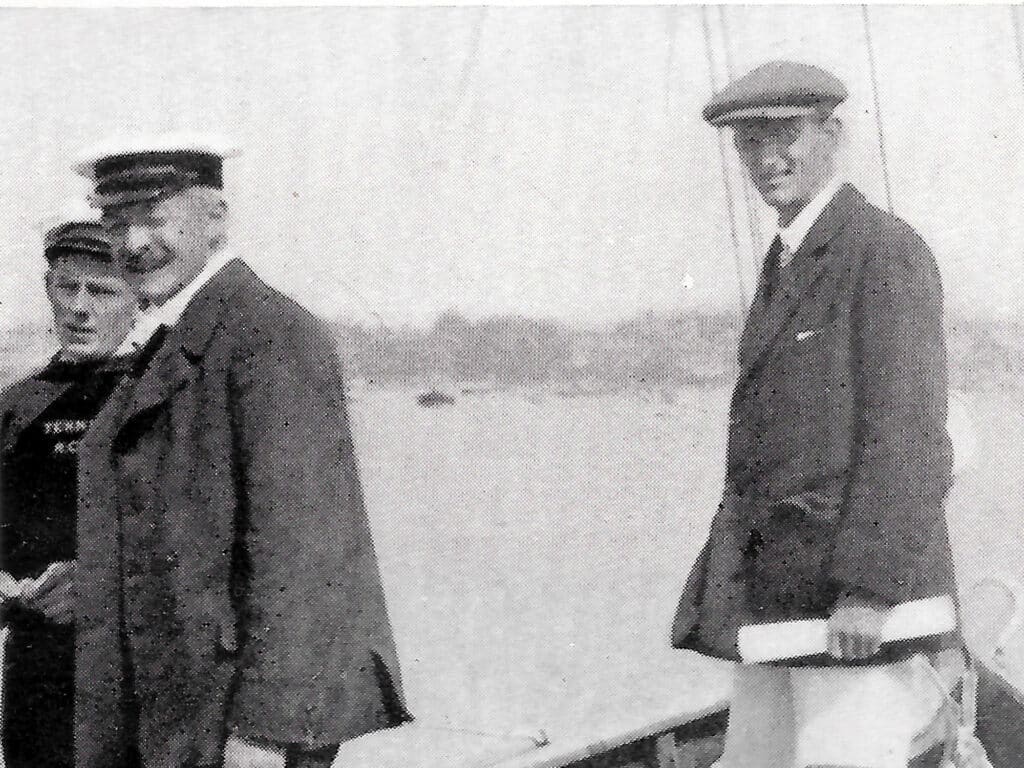

At Cowes, word of Typhoon’sexploits quickly spread through the harbor. General John Seely, the Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire, brought regards from King George V, a sailor himself. The Earl of Dunraven, who’d challenged the America’s Cup with three Valkyrie iterationsbetween 1887 and 1895, came aboard Typhoon. But the most consequential acquaintance Nutting made was Claud Worth, vice commodore of the Royal Cruising Club, established in 1880.

Birth of a Cruising Community

“Before leaving England,” Nutting wrote, “there is one institution we must mention because I hope that some time there will be such a one in our country. This is the Royal Cruising Club whose membership included many of the real cruising yachtsmen of England. Why can’t some such club be started on this side of the Atlantic?”

One of the first things Nutting did when Typhoon returned to New York that November was to propose what would become the Cruising Club of America—established in 1922, with Nutting elected as its first commodore. The club’s purpose? “To encourage the designing, building, and sailing of small seaworthy yachts, to make popular cruising upon deep water, and to develop in the amateur sailor a love of true seamanship, and to give opportunity to become proficient in the art of navigation.” You can walk down the dock of any seaside marina today and judge for yourself what kind of success Nutting had. Or, you can simply flip through these pages.

It’s not for his seamanship that we remember Nutting today. “He was a charming character and good company, a good sailor in some ways, but foolhardy and had too much courage,” recalled George Bonnell, an early CCA member.

Neither is it for his yacht-design eye, the musical equivalent of a tin ear when you compare it with others of his CCA cohort: John Alden or Olin Stephens or Philip Rhodes.

But for infectious enthusiasm, no one ever beat Nutting. Shortly after founding the CCA and publishing Track Of The “typhoon,” he became infatuated with a boat type he’d seen on a Copenhagen canal during the war: the redningskoite, or Norwegian rescue boat, as developed by the Scottish-Norwegian designer Colin Archer (1832-1921).

Virtually no one west of the Atlantic in 1924 had ever seen such a craft. He wrote: “Although strange to an eye accustomed to the racing type yacht, or to the fisherman type as we know it today in America, these boats held a fascination for me and I resolved that one day I should own one and try it out.”

On one winter’s evening, Nutting found a book that contained the drawings for a Colin Archer-designed redningskoite: “The lines scale to about 47 feet overall. After a few rough measurements we decided that if the boat were reduced to 32 feet overall, we could get the headroom under a trunk of reasonable height and sitting headroom under the side decks, and so, for convenience, we had the design photostated 16 inches overall, or to a scale of one-half inch to the foot. With these lines to work from, I spent a couple of evenings making a skeleton model.”

Nutting’s old pal Atkin helped him clean up the lines. Together, they named the design Eric for the Viking explorer Erik the Red, and Atkin published them.

It was aboard someone else’s version of a redningskoite that Nutting, with three shipmates, crossed the North Atlantic from Norway by way of Iceland in summer 1924, then set off from Greenland on September 8—after which, none of them were ever seen again.

“It is more than too bad that Mr. Nutting should not have lived to see the popularity of his child,” Atkin wrote many years later about the Ericdesign, “for some 175 sets of blueprints of the 32-footer were sold by the designer within three years after the plans appeared in Motor Boating, and many more have been sold since.” Argentine solo sailor Vito Dumas famously circumnavigated in anEric during the 1940s. And the fact that Robin Knox-Johnston’s Suhaili, the boat that won the 1968 Golden Globe solo round-the-world race, was built to an Ericdesign inspired a California entrepreneur to commission an adaptation for fiberglass-series production.

The result was the Westsail 32. Yes, the Westsail—object of so much love, and of so much derision. (“Wet Snail,” anyone?) The Westsail, with Nutting’s hand in its creation all but erased after the decades, was the very image that launched so many 1970s cruising dreams.

“This wonderfully sturdy sailboat,” ran the 1976 Playboy feature, “embodies within its wide stubby hull all of the wanderlust fantasies harbored by each of us: that marvelous dream of shucking the niggling demands of daily life and simply taking off, boosted by the wind and sea, to probe the corners of the earth. A Westsail skipper turns each cruise into a long reach to Pago Pago.”

Or to Greenland.

Nutting started a fractious 100-year conversation that we, cruising sailors all, still gather round—whether we remember him for it or not.

CW Editor-at-Large Tim Murphy is the author of Adventurous Use of the Sea (Seapoint Books, 2022), which tells the full story of William Washburn Nutting and 16 other influential cruisers and yacht designers from the past century. Murphy develops marine-trades curricula for the American Boat and Yacht Council.