It was just after dawn on September 17, 1989, and I wasn’t panicking. I was, honestly, rather proud of how calm I was.

I know, I know. Vanity comes before the fall.

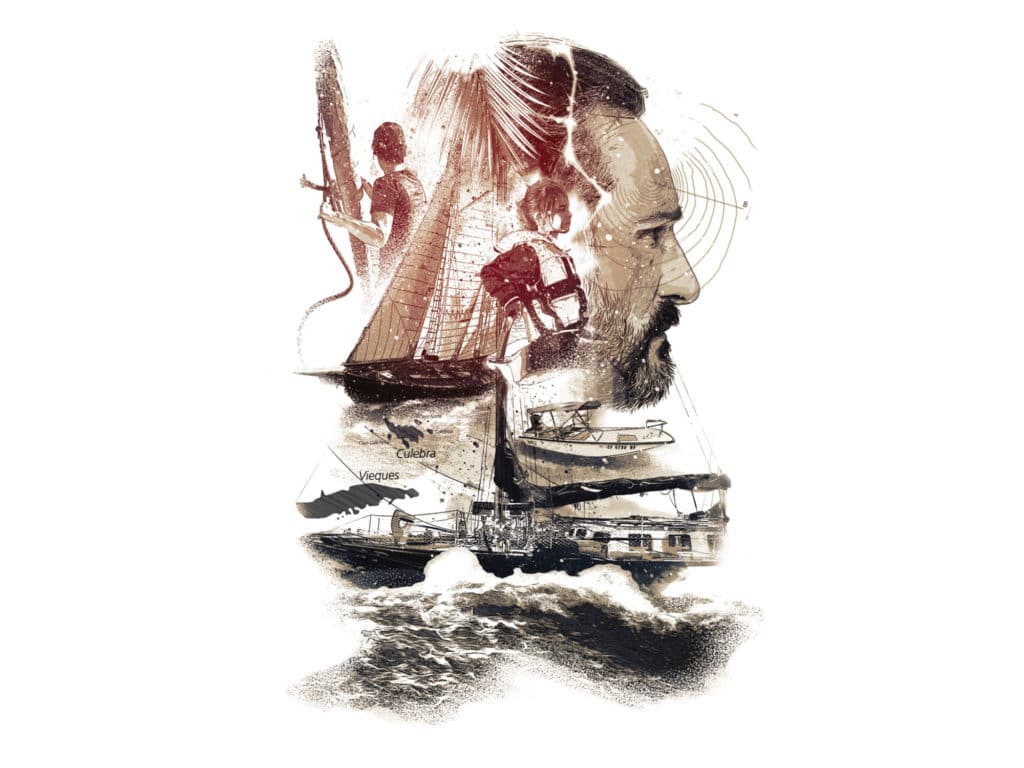

We were anchored off Culebra, Puerto Rico, in the Spanish Virgin Islands. The breeze was a steady 110, gusting to 140 knots. Hurricane Hugo, now stationary, had built to a Category 4. A large tree from the eastern ridgeline was caught in our rig, having just cracked the starboard spreader.

Not good.

My 7-year-old daughter, Roma Orion, sat in the dinette in her life jacket, gripping a strobe light in one hand and a 100-foot coil of line in the other. Around her body, we had duct-taped a waterproof bag containing her passport—if need be, for the convenience of the coroner.

My wife, Carolyn, wedged herself at the nav station. I perched atop the companionway ladder, occasionally sliding the hatch forward to check on the tree’s progress of eating our rig.

I happened to look up just as a center-console Boston Whaler with a 40 hp outboard went spinning over our masthead, its fuel tank improbably twirling alongside, still attached by the rubber-banding fuel hose.

OK, OK—I was worried. We were going to lose the boat, a 36-foot ketch I’d built with my own hands over the course of six long, hard years. We might die. So, yeah, I was kind of uptight. But I was not panicked. Panic is when your fear overcomes your rationality, when momentary stupidity overrides your brain’s ability to process. I’d never panicked afloat—and certainly not in front of my wife and child.

I was about to.

When I saw the appropriately named 68-foot schooner Fly Away dragging off our port bow, I didn’t think the boats would hit. That boat would have to “sail” with all its hooks down a considerable distance to starboard.

It sailed.

Once I realized that our ground tackle was entangled and we’d collide, I still didn’t panic. Even if our boat sank, we’d be able to swim ashore. Hey, we were sailors, right? Water was our medium.

Alas, when we came together, Fly Away’sstarboard aft chainplate was just forward of my stout bowsprit. We were now just about as tangled as two heavy-displacement cruising vessels could be. Fly Away would have to snap off my bowsprit and I’d have to tear out its chainplates before we’d separate.

It took a while—a gut-wrenching while.

The sound was amazing, and not in a good way. Roma Orion started screaming. Carolyn was yelling something that I couldn’t catch. Rigging snapped. Chainplates tore. Our bowsprit split. At one point, our masthead became entangled, and we repeatedly separated and smashed back together violently, like two rhinos careening toward death.

Rational thought became difficult, but still, I did not panic. In fact, it was rather awe-inspiring. At some point, I giggled. Why not? My chainplates hammer-clawed entire topside planks out of Fly Away, revealing her varnished interior, beautiful rugs, and gimbaled kerosene lamps. Somehow—impossibly—one of our stanchions and its base punched through our deck. It wiggled there, its lifelines still attached, as major water began pouring into our vessel.

No panic.

Fly Away’s skipper appeared on deck. I was worried he was going to try to deploy fenders between our vessels—we were way beyond that now. I slid my hatch and shouted at him over the howl: “Careful! Don’t get hurt!” He was sobbing.

All this madness seemed to have a calming effect. We were going to lose the boat and be driven ashore. Oh, well.

Then, Fly Away’s bowsprit started clubbing us, with huge wooden smashes from a 12-foot-long demonic club.

My companionway hatch was shattered. It was crushed. It wouldn’t open. But it had to open, or we’d die like sinking rats in a trap. And we were taking on water.

The thought came to me wholly unexpectedly, like a rising bubble of fear within my churning stomach, up through my chest: We were going to drown inside our vessel, wet and entombed.

I panicked.

First, I tried pushing and pulling the hatch. I tried punching it as hard as I could with my bare fist. Nothing. “Oh, God! Oh, dear God! Please, God!”

I began smashing my head savagely into the hatch—using the full force of my leg muscles to do so.

Now, dear reader, the chances of me headbutting my way through this particular hatch were nil. I’d built it with my own hands to survive Cape Horn. But I tried, as hard as I could, with as much force as my legs could muster.

Then, a moment of blackness. A sensation of falling. And a reawakening of clutching—no, hugging—the ladder. I took a deep breath, then another. This gave my brain a chance to reestablish its dominance.

We had three hatches on Carlotta. Two still worked. There was nothing to panic about.

I have not panicked since. And as gruesome as those couple of moments were, they taught me compassion for those unfortunates in the grips of such momentary irrationality. Which isn’t to say that I haven’t been around other people panicking at sea. I have, all too often. So frequently, in fact, that I now often realize the signs early enough to head it off.

But before we get to that, we should note that modern cruising skippers have a tough job. Back in the old days, a skipper could bark orders at his crew. He could make them do what he wanted. His job was clear: to bring the boat, crew and cargo into port—not to be liked.

Today’s skipper has all of that on his shoulders, plus the fact that, in pleasure boating, there should be, by definition, pleasure. The crew is supposed to enjoy themselves—even as the Grim Reaper swims aboard. And if they ain’t, then that too is the skipper’s fault.

One common scenario is the ratcheting up of fear among two or more of the crew. One says, “Gee, it’s really blowing.”

The other says, “Gusting to gale force.”

“Gale?” chips in a third. “And come to think of it, isn’t this hurricane season?”

Then it becomes, “What about the life raft?” or “Why not signal the freighter?” or “Why not call a mayday, just as a precaution?”

A good skipper learns to head off these fear-blooms quickly.

Think team. Get everyone doing something productive during an emergency or heavy weather. They’ll be less frightened if they have a task they must perform.

Talk to them. Reassure them. While remaining fact-based, make light of the situation. I always make silly jokes about taking reefs in the ensign, or having the paint peel off the topsides in a blow, or finding the barometer in the bilge because the storm pressure dropped so low.

The subliminal message is: This is a gale, yes, but it is also an escapade. And, once survived, it is a feather in your cap, a wonderful story for your grandchild.

I have an independent on/off switch on my windspeed. There’s nothing worse than a fearful landlubber saying aloud to the rest of the crew: “Here’s a huge gust, 44 knots, 47, damn, that’s the worst yet! And the baro is still falling! And these seas aren’t even mature now—just wait until night! Why, I’ve heard of boats pitchpoling in less breeze!”

Don’t let it happen. Give that crewmember a good job, perhaps flaking down the Jordan series drogue so that it will come out of the bag without snarling, for example.

Always inspire confidence. You have a plan, and you’re sailing it. You’ve been here before and lived to tell the tale.

If you’re running off before conditions become extreme, then say: “When it gets rough, we’ll think about streaming a slowing drogue. Of course, we could deploy our Jordan series drogue and then be perfectly safe.”

If you’re hove-to in building conditions, then mention how easy your Paratech is to deploy and how, once it’s streamed from the bow, life is a cakewalk. (Such devices off the bow can be very safe if the vessel can stay attached and doesn’t snap off its rudder. However, the motion is extremely violent without a steadying sail.)

Never, ever allow the escalation of any talk about getting into a life raft—many, many people have died because they got into a life raft when they should have stayed with the ship. I think of life-raft talk as siren calls—words that lure sailors to their deaths. “We’re only going to step in a life raft from the spreaders,” I say.

Ditto with distress calls on the single sideband radio—save your breath. As skipper, bear these great truths in mind: Your vessel is your life raft; and you are the solution to all your problems. Look first within yourself for proactive solutions, not outside for rescue.

A friend of mine owns a cruising ketch in the 70-foot-range with twin satellite domes in his mizzen. During gales offshore, he boots up real-time radar images of the storm, and tries to push them away from his vessel with his cursor.

I kid you not.

Don’t be that guy. He spent all his money on his vessel and its glitzy cockpit display, and nothing on safety equipment. He was so busy updating the firmware to his software that he forgot to learn how to heave-to.

Being an offshore skipper entails serious responsibility. Psychological crew management—a fancy phrase for keeping your crew safe, calm and happy—is part of the job. If a crewmember is having a particularly tough time, offer a hug. Engage. Shower attention and affection. Ask about a kid—did the daughter really hit a Little League home run? Is it true the son has an interest in ballet? Did the family ever buy that car they were talking about?

Get the mind off the blow. Focus on the everyday mundane, and the fearful what ifs lose their bite. If the mast is up, the keel is down and the bilges are dry, then chances are, you’ll all see the dawn.

Most of all, tell the truth—but wrap it in a confident, in-control smile. The difference between ordeal and adventure is attitude.

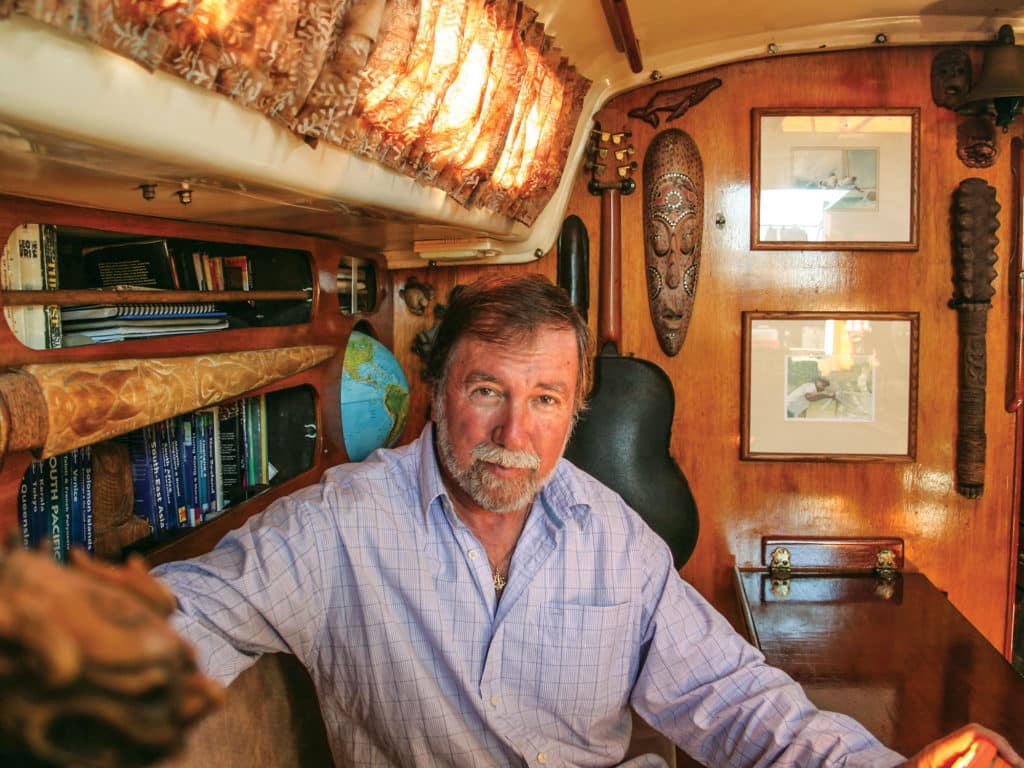

Fatty and Carolyn Goodlander are currently dusting off their pilot charts in Singapore, yearning to chase the horizon once again.