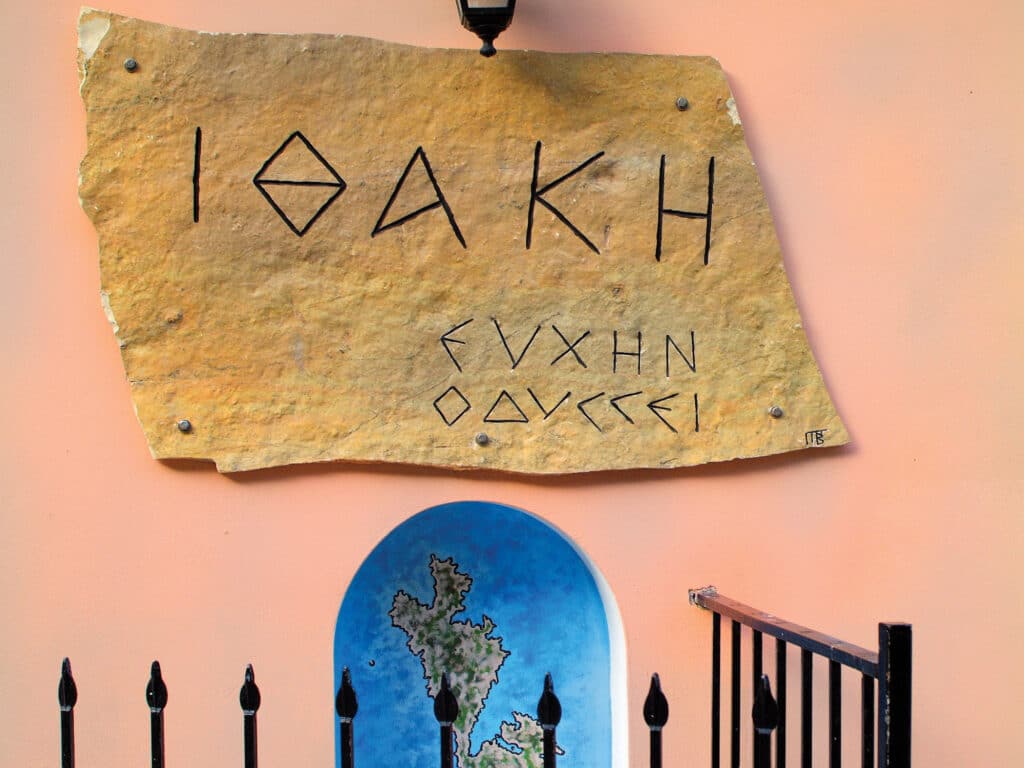

Sailing south from Lefkas in the Greek Ionian Sea, I found a calm anchorage in a deserted cove on the east side of the hilly, wooded island of Ithaca. This was the home of Homer’s hero Odysseus, who was seeking to return home to his wife, Penelope. I, on the other hand, was seeking to get away from home and find a secure anchorage for the night. In deference to Odysseus, I kept the sails up in a desultory 10-knot breeze. I was always a sucker for the appearance of inauthentic antiquity. My Hanse 415 Adagio’s refrigeration, however, remained on with the Greek beer chilled. Odysseus would have been thrilled; the god Poseidon, probably not.

The next morning, I sat down in the cockpit to enjoy a freshly brewed cup of coffee. No sooner had I settled down than I heard the raucous noise of a high-speed powerboat.

The only vessels that traveled that fast in the Mediterranean, apart from Italian speedboat cowboys, were the coast guard. Sure enough, the Hellenic Coast Guard roared into the bay and, slowing only a little, executed a tight U-turn around my boat. Their wake rocked Adagio violently. Annoyed, I nevertheless waved with what I hoped might be taken as a friendly but not overly familiar gesture. With no acknowledgment, and seemingly assured that there were no illegal migrants or unsanctioned toga parties aboard my Italian-flagged vessel, they sped off into the horizon. Paradise, or the illusion thereof, is invariably a fleeting phenomenon.

With no agenda or itinerary other than to get Adagio out of the water and fly home to Southern California in early November, I returned to my coffee and pondered the day. Avoid expectations, be open to what shows up, and let the day unfold, I reminded myself. The thought of calling my office or clients in the States did not even occur to me.

Conventional-cruising narratives had always told me that to genuinely experience a cruising lifestyle in locations such as the Mediterranean, I needed to fully drop out from my domesticated land life. This would include abandoning my business and the work I enjoyed, my friends, skiing, my home, and my physical-fitness routine. For me, however, this posed what I initially saw as an insoluble conundrum: Did I really want to be that liberated?

As much as I was passionate about cruising, I also loved my lifestyle in Ventura, California, and, yes, my joint-custody dog, Murphy, from a recent divorce.

In 2008, at age 60, I came to the stark realization that my biggest enemy in life was time. This awareness led me to the conclusion that if I were going to live the balance of my life to its fullest, then I needed to start doing it now. I did not want to have any regrets, and I dreaded finding myself in a conversation with my orthopedist that began: “Well, Jim, you know you are at an age where you need to start slowing down. Have you considered taking up miniature golf?”

In the fall of that year, I chose to do the Baja Ha-Ha—the fun cruise from San Diego to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico—with a friend. For the balance of the fall, winter and early spring, I mostly solo-sailed my 41-foot Wauquiez in the amazing Sea of Cortez.

I discovered that I thrived in solitude with total self-reliance, and I loved the ability to get away from it all, if only for two to three weeks at a time. Moving around the sea, I would berth my vessel in a secure marina for several weeks, and fly home to resume my work and land life in Ventura.

By fall 2015, I had spent two seasons in the Pacific Northwest, two seasons in Mexico, and eight months in the Hawaiian Islands following the Transpac race. Commuter cruising, as I came to call it, had become a chosen and well-trodden—albeit still adventuresome—lifestyle. I had become comfortable, if not confident, in my ability to schedule and meld my work, my team, and my cruising life. This skill allowed me to spend at least three to four months a year on the water.

In winter 2015-16, I looked for new commuter-cruising grounds. Cruising to the South Pacific did not appeal to me; where could I park the boat and return home? Nor did I relish long, solitary ocean passages. My limited bareboat experience in the Caribbean had left me with the impression—superficial, to be sure—that there was a repetitive sameness to these admittedly beautiful islands. The Mediterranean, on the other hand, held the allure of a rich history, varied cultures, big cities, quaint villages, and a friendly and engaging people. It also offered an established cruising infrastructure and secure marinas. I rationalized that if I continued working, I could afford to purchase a better boat in the Mediterranean.

I bought the three-year-old Adagio in spring 2016 just outside Genoa, Italy, and began the first of four seasons, each one around five months, in the Mediterranean. My initial goal was to cruise the entire Med in two years. I subsequently modified that to a more realistic four years.

Adapting my flexible itinerary to such constraints as the pesky 90-day EU visa and the reality that there is, at best, a Mediterranean cruising season of six to seven months, I soon developed a lifestyle that had me in the Med in early April and out of the water in early November. I’d return to California in July and August for a five- to six-week working hiatus. My time afloat in the Med became more like two- to three-month mini sabbaticals, and my working life adapted accordingly.

July and August in the Mediterranean were hot, crowded and expensive. Did I really want to be seen in trendy marinas in that heat while paying more than $400 a night for a mooring, if I could even get one? Cruising in the shoulder seasons, however, came with the challenge of more-variable weather. The sailor’s adage that the wind blows either too much or not at all in the Med I found to be especially affirmed in the spring and fall.

One of the pluses of cruising the Med is that it rarely required me as a solo cruiser to do any overnight sailing. And I was almost always within cellular range. Now, with devices such as Starlink and videoconferencing, conducting business afloat in the Mediterranean is no more difficult than doing it remotely in the US, aside from the time difference.

Like any cruising area, the Mediterranean does have its drawbacks and risks. There are some definite no-go areas, such as most of North Africa and the Middle East. And there is the ongoing illegal migrant crisis.

And then there is the challenge of Med mooring singlehanded—especially in Greek and Turkish waters, where I needed to drop the anchor and back down, all while steering to hit my slot on the quay. It’s a good case for having three hands, or four if you have a bow thruster, which Adagio did not have. As with much of cruising, you adapt, though I would still embarrass myself from time to time.

The Mediterranean also offered an unexpected bonus: the opportunity to engage with a friendly, culturally diverse cruising community at anchor and in the marinas. Singlehanded cruisers are a bit of a rarity in the Med (I met only one other) and a curiosity. I got used to predictable questions of “How do you do it?” and “Don’t you get lonely?” Yes, I would think, that’s why I initiated this conversation with you. Some would speak of having met other solo sailors, invariably prefaced with the word “crazy,” as in, “He was a crazy Swede.” Perhaps I earned the moniker of “that crazy old American who ran and had a rowing machine on his boat.”

My advice to aspiring commuter cruisers is to start with a smaller boat and go for shorter durations. Learn, adapt and, in some cases, endure.

Most of us have multiple passions in life. For me, these became particularly hard to let go of the older I became. Is there a way for each of us to craft a cruising lifestyle that allows us to pursue all of these? I believe there is. Leap, as nature essayist John Burroughs put it, and the net will appear.

Jim Eisenhart is the author of the forthcoming book Nomad Sailor: Adventures Commuter Cruising the Mediterranean. He currently owns a Moody DS41 and has been commuter-cruising the US East Coast and Bahamas.