The last of any cruising cobwebs were shaken out as we sailed our 47-foot Stevens Totem across a chunk of the Pacific Ocean. Our recent passage from Los Frailes, Baja California Sur, to Honokōhau, Hawaii, was within 100 nautical miles of the distance we sailed from Mexico to French Polynesia.

That’s a significant passage.

By the numbers, we covered a distance of 2,805 nautical miles. It took us 16 days, eight hours at a top speed of 12 knots and an average speed of 7.2 knots. Our best 24-hour run was 186 nautical miles. We burned just 12 gallons of diesel and 4 gallons of gasoline. And while we did not catch any squalls, we did stop counting after 19 flying fish landed on deck.

Two additional crew contributed meaningfully to the passage: our son, Niall, and our friend, River. Niall, who is two years past graduation from Lewis & Clark College, left his job in refugee services earlier this year. Of course, he intimately knows the floating home he grew up aboard. River is a boat-savvy friend we met while he and his wife were cruising in Mexico in 2019. He was supposed to join Totem to sail to the South Pacific in March 2020, but we all know how that year panned out. His gentle strength and can-do attitude make an excellent addition to a passage. Plus, he brought the chill that I sometimes needed.

After teaming up for the first couple of nights, we did two-hour rotations at night and ad-hoc watch-standing during the day. The help was a luxury that Jamie and I may miss for our next big leg to the Marshall Islands.

Conditions Underway

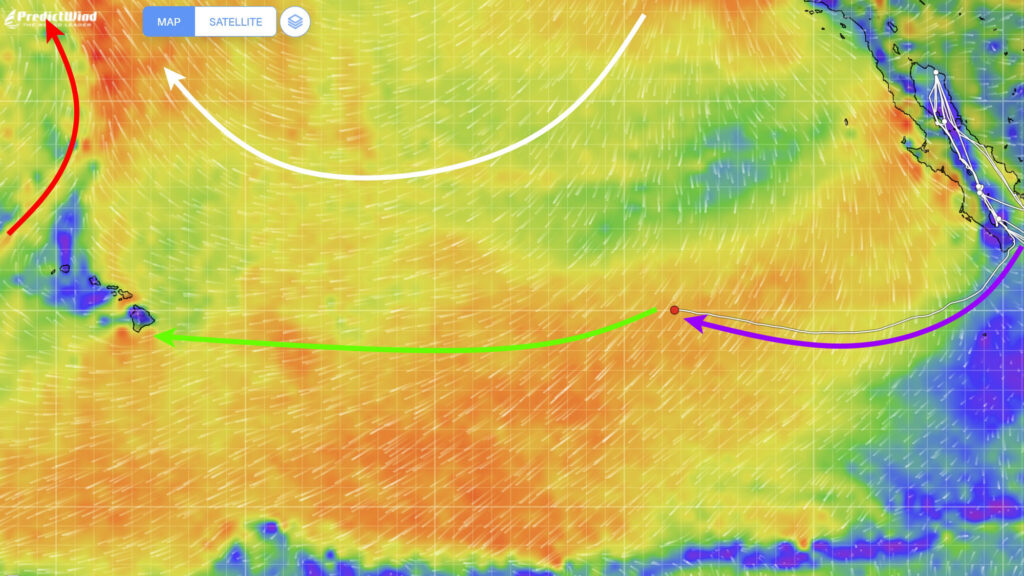

Conventionally, this passage benefits from northeast trade winds; the angle would put apparent wind at or just behind the beam on Totem, where our boat shines. These conditions are based on the establishment of the North Pacific High (a high-pressure weather system bringing stability and generally mild conditions) as spring progresses.

In the days leading to our departure window, the high developed into a nice, stable size and location. In our pre-departure crew meeting, my husband, Jamie, discussed our weather expectations for the passage: we’d time our departure to get around Cabo San Lucas in moderate conditions, we’d spend 24 to 36 hours of close reaching in 15 to 18 knots; and we would shift into broad reaching and then running as we got west under the high.

Jamie’s only concern was the high growing bigger or shifting south, leaving us with little to no wind. He expected we’d drop 3 to 5 degrees south of the rhumb line route west to the big island. We also expected decent stargazing along the way.

Our passage did not follow this script.

There were two subtle changes to the North Pacific High. First, a low pressure system moved eastward in an arc over and down into the top of the high. Second, a stationary low formed near Hawaii, causing torrential rain and flooding. That low nudged the high a little farther north.

Where we were, compressed trades came out of the north. Totem’s speed often ranged from 7 to 10 knots, pulling our apparent wind angle well forward of the beam: not close-hauled, but 65 to 80 degrees was far from the broad-reaching to running we expected. After a week, the wind finally began to clock northeast. On day nine, the apparent wind angle was at 130 to 150, and we set up a wing-on-wing sail plan.

This was a more active passage than most. Cooking was a challenge. I complained at times that cooking required arms like an octopus to hang onto everything, but I appreciated the mostly starboard tack, as it makes our galley is easier to use. One passage win? Discovering that the roll of thin silicone mat I purchased for baking also serves as excellent nonslip under plates.

Another win was minimizing garbage. We throw organics overboard, but not glass or cans. We reduce packaging before departure. We cut soft plastics and stow everything in containers until landfall. How we make it work (and dealing with garbage while cruising more generally) is described in much more detail here.

Also unexpected were the number of chilly nights and gray skies. Starting on our second night at sea, there was rarely sun until day 13. That hampered our solar power generation. Those 4 gallons of gasoline burned? Running the generator to top up our batteries.

Some stargazing would have been nice, but overcast weather prevented that. It also hampered power generation. Totem has 1,215 watts of solar. In Mexico, this was enough to meet all power needs, including making hot water. With the cloud cover, we had to run the generator several times to keep up with power demands.

Gear Failures

We lost a Corelle dinner plate. It’s supremely durable dishware until it hits a surface just right and splinters into 16 million shards. It was our second plate in 16 years to break in dramatic fashion.

We also had a shackle failure on day 14. Jamie explains: “Pre-departure, I ran out of seizing wire on the last shackle to be moused, securing the genoa head to the upper furling swivel. Instead, I used a zip tie. The shackle pin still backed out, and gravity pulled the genoa down. Naturally, this happened in the dark hours before dawn. The sail slid down the foil, and since it was poled out to starboard, slipped into the water and trailed alongside like a well-behaved, wet sheepdog.”

Totem kept cruising along at 7 knots as our genoa skimmed the surface of the Pacific. It happened while Jamie and I were in the cockpit, chatting, as he turned the watch over to me; half of the crew was awake, the other half quickly roused.

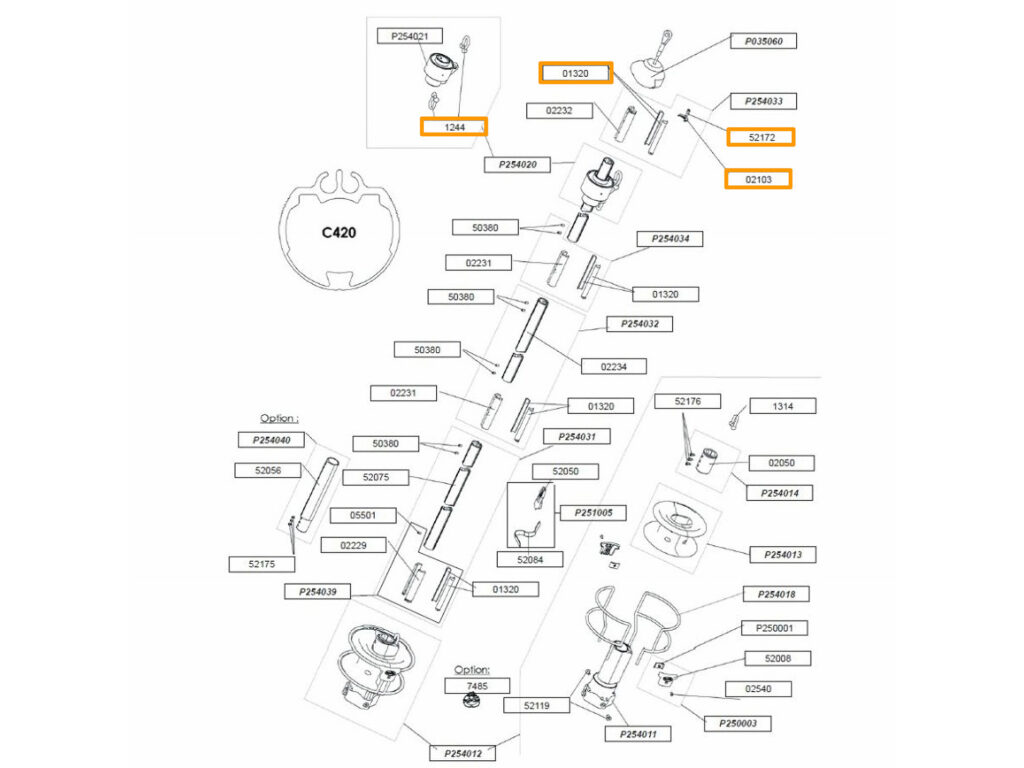

It was a demonstration of quality teamwork as the crew got the sail, still attached at the tack and clew, back on deck and secured. Closer inspection after landfall turned up more.

As Jamie explains: “After the passage, I went aloft to retrieve the furler swivel and halyard from the top of the foil section. There, I was surprised to find that the endcap on the foil section was gone. Puzzled, I tried rotating the foil and found that it locked up in one direction. I suspect that when the shackle opened up, the genoa luff tension released, causing the halyard to recoil and pull the swivel up into the end plate—apparently with enough force to rip out the machine screw, which then fell inside the foil, causing the furler to bind. Should be easy to retrieve it, but it means another trip up the mast.”

I helped Jamie go aloft again to retrieve the bits. Then, it would be a matter of ordering replacement parts for the furler and some hand-sewing to repair the chafed top of the genoa. It got chewed up when it flogged at the masthead before making its graceful descent for a swim.

In Hindsight

We did not have fishing gear on board. Our kit went walkabout during the refit. Initial plans were to replace it before we left Mexico, but with the limited selection, we opted to wait until we arrived in Hawaii. Sure enough, even a convenience store in Hawaii had a better selection of lures and line.

All in all, though, this successful passage was a significant milestone. Putting about one-third of the Pacific Ocean between Totem and Mexico, after several false starts in the last few years, was meaningful.

Jamie and I have set off on a new chapter of our cruising life. We were gratified that our preparation and shakedown had been solid. The post-refit Totem, which still feels like a new boat in many ways, is ready to be our oceangoing magic carpet, once again.

Want to see some video from the trip? We had fun making a few clips; check our Instagram.