On May 1, 2024, Donald M. Street died in Glandore, Ireland, at the nimble age of 93. He’d just finished commissioning his International Dragon Gypsy for this year’s racing season. He was also looking forward to racing in 2029 at a regatta celebrating the 100th anniversary of the classic Johan Anker design.

Don was always an optimistic guy. He was also a true hero of mine, on many levels. He was one of the reasons I’d sailed to the Caribbean, to rub shoulders with such larger-than-life sailing legends before they disappeared.

I’ll never forget our initial meeting. It was in the late 1970s. He’d sailed into Long Bay, St. Thomas, aboard his $100 yawl Iolaire, which he’d salvaged off the beach in Lindbergh Bay in 1959. There was much welcoming, yelling, laughing and swearing as Don tacked through the fleet. Everyone involved in the laborious docking procedure of his engineless yawl seemed drunk, and happily so. Dozens of dinghies acted as towboats, tugboats and “let’s add to the confusion” boats.

Despite the towline chaos, Don didn’t seem the least bit uptight. His attitude seemed to be that if worse came to worst, he’d just aim for something cheap, like a piling or seawall. He was obviously happy to be back in paradise. He’d just sailed from Bermuda or Ireland or the Mediterranean, or perhaps all three.

He handled his vessel well in close quarters, occasionally having to shift his ever-present Greenie beer from one gnarled fist to the other.

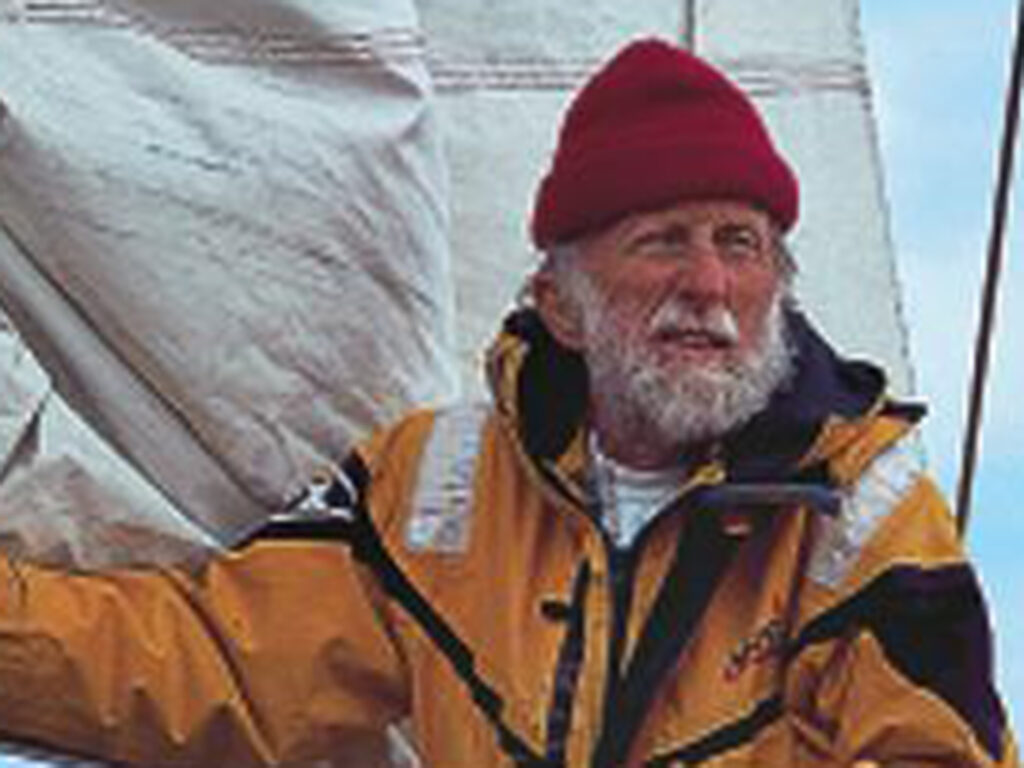

He wasn’t a big man. He was unexpectedly slight. But he had a large presence and obviously loved the spotlight. There was a sparkle in his alert eyes, a spring in his step. And he moved around his rough-hewn deck with the grace of a tipsy dancer.

Obviously, he wasn’t rich. He wore cast-off clothes and mismatched flip-flops of different sizes and colors, and a sweat-stained white floppy hat with a lanyard clipped to his faded T-shirt.

Why was I—am I—so intrigued by Don? Because he was everything I wanted to be: a sailor, a raconteur, a wood butcher, a notorious international cheapskate and a world-famous marine writer. He was all my aspirations rolled into one.

Oh, and he was a contrarian, always willing to engage in conversational combat wherever and whenever contentious sailors gathered around fist-banged rum shops, from Maine to Trinidad.

In fact, he had every skill I desired as a sailor, save one: He wasn’t much of a mechanic. Twisting wrenches wasn’t his thing. (The US Navy had attempted to force him to learn diesel mechanics, but Don outfoxed the brass by submerging within the submarine fleet.)

His solution to his lack of mechanical ability was simple. He’d just unbolt and deep-six every “infernal combustion engine” from every yacht that he could. He loved converting auxiliaries into moorings.

“Nothing is more satisfying than the splash of an iron breeze,” he’d say with a playful wink. “Why, I’d never disgrace Iolaire’s bilge with one of those stinking, oil-oozing, demonically possessed thingies.”

“Yank it out, Fatty!” he’d yell at me. “You’ll be a better sailor without it.”

Amid all the colorful Caribbean characters and wonderful waterfront wackos who gathered on Iolaire’s deck, only one individual stood out: Don’s sailing companion and second wife, Trich. She seemed like a perfectly normal individual. Weird. Disconcerting, even. Perpetually youthful, she often wore a T-shirt that read, “I’m Don’s wife, not his daughter.”

Don was also a man of great fun and stubborn opinion. For instance, in addition to diesel auxiliaries, he also despised GPS units. He waged a one-man war (in the pages of Caribbean Compass and in person) against their use right up to the millennium.

But back to our initial meeting in Yacht Haven. As I marveled at his running rigging (I’m using the phrase for chafed lines loosely here), he ambled forward, smiled and said proudly, “Tennis balls.” His voice was oddly high—hence his nickname, “Squeaky.”

I could see the ancient, hanked-on headsail, which Don had probably retrieved from a dumpster after following Ulysses around. It had major problems.

“When the clew pulls out of your headsail,” Don pontificated to me, “just bunch up the fabric around a tennis ball, then triple-wrap your sheet just forward of the tennis ball, and tie the whole mess with a bowline. As the bowline slips down, it will clinch up the fabric around the tennis ball, and, hell, you can sail through a gale or two, no problem.”

This works. I know. My hero taught me.

Note that Don didn’t say “if” your clew blows out or “in the rare event of” but rather “when the clew blows out,” as if this is how real sailors cleverly manage their sail inventory.

Don saw me marveling at his hodgepodge wooden deck. “More Dutchman than The Hague,” he said proudly.

That simple, five-word sentence sums up Don perfectly to me, both then and now. He didn’t treat me like an idiot; he figured that I knew The Hague was in Holland, and that Dutchmen have a reputation for thrift, and that replacing a long plank with many short planks (or Dutchmen) was a common practice among frugal sailors. He had a sense of humor, and he had the ability to turn weakness (going to sea with an oft-patched deck and a rotten headsail) into strengths (carrying on with the voyage) while demonstrating a simple, time-trusted solution to a complex problem (how to cruise endlessly with empty pockets).

Don did all this in some strange sailor-conspiracy mode that indicated we true sailors understood each other. If landlubbers didn’t, why should we care?

He was famous for his frugality. Once, in a sailors’ dive in Douarnenez, France, in 1992, he bought me two beers on the same day. My wife, Carolyn, was stunned. “Damn,” she said. “That’s an international sailing record.”

Yes, Don could squeeze a penny so hard that Abe Lincoln would cry. It was part of his charm. If Don thought it was worth carrying aboard his boat, it was most definitely.

Why was I—am I—so intrigued by Don? Because he was everything I wanted to be: a sailor, a raconteur, a wood butcher, a notorious international cheapskate and a world-famous marine writer. He was all my aspirations rolled into one.

Don was also a diverse, accepting fellow. I’ve partied with him and a bunch of giggling Rastas in Bequia, seen him conferring with the business elite of the BVI, and gotten drunk with him at a soccer hooligan bar in the United Kingdom. Oh, and one strange evening in 1990, I sipped champagne with him and Bill Koch aboard the maxi Matador after its boom broke. (Don was playing rock pilot during the Maxi World Championship on St. Thomas while I was scribbling for the Marine Scene.)

Don would buttonhole anyone, including famous sailors. Paul Cayard, Gary Jobson, Dennis Conner, Peter Holmberg, Tom Whidden, John Kolius and Jim Kilroy were all listening to Don’s sea yarns at various points during the 1990 maxi regatta.

Yes, Don knew every famous cruising sailor—and he knew them from an early age. When Don was 15 years old, L. Francis Herreshoff (yes, the L. Francis) was encouraging him to become a naval architect. How cool is that?

Another thing I liked about Don was how unpretentious he was. Once, while I was anchored in a crowded harbor on Isla de Margarita, Venezuela, Don sailed in. He tacked through the dense anchorage to a large, empty spot in the middle, and promptly ran aground.

Without batting an eye, Don whipped out pen and paper to carefully record his lat/lon via a hand bearing compass, to assist future generations of yachtsmen. Do Imray charts have all the rocks marked? You betcha, thanks to the tireless Don Street.

Ditto his cruising guides, which, Caribbean sea gypsies would fondly joke, Don originally wrote with a quill pen on foolscap by the light of a tallow candle.

He was first published in Yachting in 1964, and then began earning money from every marine publication that purchased ink by the 55-gallon drum. While building my 36-foot ketch, Carlotta, I poured over his books Seawise and Ocean Sailing Yacht, both treasure troves of practical, tried-and-true cruising info.

Don wrote hundreds of marine articles, many for Cruising World. He always had his own slant on things, claiming that the magazine’s Aussie founder, Murray Lloyd Davis, managed a small parking lot next door to Cruising World, and that revenue from the parking lot kept the publication afloat in the early days.

I loved to hear Don’s stories about Carleton Mitchell, three-time consecutive winner of the Newport Bermuda Race (’56, ’58 and ’60) and author of Islands to Windward and Isles of the Caribbees. I’d been aboard his boats Caribe and Finisterre, and was thrilled to hear Don tell sea yarns about him and Carleton pacing their wooden decks in the 1950s. Don was on a first-name basis with all the sailing heroes of my youth: Irving Johnson, Eric and Susan Hiscock, and Miles and Beryl Smeeton all knew him.

Don cared about everything pertaining to cruising vessels and the sailing lifestyle. If you called yourself a sailor but didn’t know the difference between carvel or lapstrake planking, he’d shake his head in disgust.

“The guy didn’t even know what a limber chain was!” he’d rant to me. “Didn’t know his garboard seam from his horn timber! I told the guy, ‘There are no ribs on a boat. Wooden boats have frames, man, not ribs!’”

Don learned to sail on Long Island Sound, born into a New York banking family. One of his first jobs was on Huey Long’s Ondine, a 53-foot Abeking & Rasmussen yawl, first as deck swabbie, then as skipper (with no increase in salary).

Soon, Don was rubbing shoulders with Charlie “Butch” Ulmer and other sailing rock stars of the day, many of whom mentioned the glories of cruising the Caribbean. Don impulsively decided to fly in and check out the scene.

Landing via airplane on St. Thomas on a Friday in the mid-1950s, he was working as a yacht surveyor by Tuesday. He drifted into writing about the growing charter industry after Pulitzer Prize-winning author John Steinbeck (a frequent St. Thomas visitor who often chartered with famed Virgin Islands sailor Rudy Thompson) told Don that the key to becoming a writer was to write six days a week, six hours a day, and then wear down the editors with his submissions.

Don did exactly that. He was blasé about his writing. When I was a copy editor at Jim Long’s Caribbean Boating, he’d drop off piles of notated napkins and pieces of scribbled, rum-soaked bits of paper. He’d say, “See what you can do, Fatty. It’s all funny stuff, know what I mean? What should we call it? Does ‘Don’s Caribbean Capers’ sound like a good title?”

He was irrepressible. Nothing fazed him. At some point, Don was trying to sell me yacht insurance, despite it being easier to get blood out of a turnip. Then he hooked up with Imray charts. The man had incredible chutzpah.

We also sailed on many of the same boats, though never at the same time. I acted as navi-guesser on Paul Adamthwaite’s Stormy Weather for many years, leaving only when things devolved into fisticuffs during the infamous Great Bermudian Pillow Mutiny. Don slotted on board after the Monkey Crew revolted. He sailed with Paul during Stormy’s last Fastnet under Paul’s ownership.

Oh, Don was a rascal. He soon found that many folks wouldn’t charter Iolaire because she was engineless, a fact that Don then conveniently forgot to share. If a charter guest demanded that he crank up the engine, Don would agree to “motorsail” with his loud Stuart Turner genset thumping in the background.

Don also had an incredible memory. No matter where we’d meet in the Atlantic Basin or how long we hadn’t seen each other (or how many Greenies he’d consumed), Don would immediately launch into whatever marine bone of contention we’d previously been arguing about. For a decade or so, we hotly discussed the minutiae of cranse and gammon irons—exactly why, I can’t now recall. (A cranse iron holds the fore, bob and whisper stays at the end of the bowsprit, while the gammon secures the staysail stay and holds down the bowsprit as it comes off the deck.)

Was there tragedy in Don’s life? Yes. In the mid-1950s, his first wife was murdered on Grenada while Don was off-island. She was killed by a machete-wielding local. Don was 25 years old at the time with a young daughter named Dory. (Later, he had three sons with the Irish lass Trich, who raised the entire brood.) Don never spoke of the murder, to my knowledge.

But he did find interesting ways to say whatever he wanted to say. There was a tiny storage place under Iolaire’s bridge deck—perfect for a couple of fenders. Often, the sound of a clacking manual typewriter could be heard emanating from there, and occasionally, a young female graduate of Vassar or Goddard would emerge. “I’m Don’s executive assistant,” she’d say while wiping the mildew out of her hair, “tidying up his latest manuscript.”

No, they didn’t want to be rescued from their hovel. “I’m having the time of my life,” one told me. “Making literary history in the Caribbean. What could look better on my CV?”

I think the last time I saw Don was around 2010 in the Canaries. It was just before the ARC Rally, which was run by our mutual friend Jimmy Cornell. Don was in fine fiddle—a Greenie in one hand and a glass of Mount Gay in the other.

We kept in touch via email. Don was never shy about expressing himself or seeking help with his many doomed causes.

“They’re trying to make me wear a life jacket, Fatty,” he complained about modern yacht racing, “Over my dead body.”

Another email ranted about folks going offshore with electro everything. “They don’t even have manual bilge pumps,” he’d write, aghast.

The most amazing thing about Don was that, after all those sea miles and all those crazy Caribbean capers, he died of natural causes, surrounded by his loving family and friends.

Fair winds, my friend. Give ’em hell in Fiddler’s Green.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Cruising World does not condone the practice of disposing of man-made materials in the ocean, and strongly encourages the use of lifejackets on board at all times.