I wrote these words in the foreword of my book World Cruising Routes: “Sailing routes depend primarily on weather, which changes little over the years. However, possibly as a result of the profound changes that have occurred in the ecological balance of the world environment, there have been several freak weather conditions in recent years. The most worrying aspect is that they are rarely predicted, occur in the wrong season and often in places where they have not been known before. Similarly, the violence of some tropical storms exceeds almost anything that has been experienced before.”

I continued: “The depletion of the ozone layer and the gradual warming of the oceans will undoubtedly affect weather throughout the world and will increase the risk of tropical storms. The unimaginable force of mega hurricanes Hugo and Andrew should be a warning of worse things to come. All we can do is heed those warnings, make sure that the seaworthiness of our boats is never in doubt, and, whenever possible, limit our cruising to the safe seasons. Also, as the sailing community depends so much on the forces of nature, we should be the first in protecting the environment, and not contribute to its callous destruction.”

It’s been 30 years since then, and every word still holds true. Global weather conditions have seen major changes, especially in terms of the location, frequency, intensity and extra-seasonal occurrence of tropical cyclones. In its sixth assessment on the impact of climate change, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stressed the urgency to act, warning that climate change is causing dangerous disruption in nature, and is affecting billions of people.

Our oceans are getting warmer.

The Arctic ice cap is melting at a faster rate than in any recorded time, as reported from Greenland.

The ice shelf surrounding Antarctica is diminishing at an unprecedented rate.

Tropical-storm seasons are less clearly defined and more active. Extra-seasonal tropical storms are more common.

The Gulf Stream rate is slowing down.

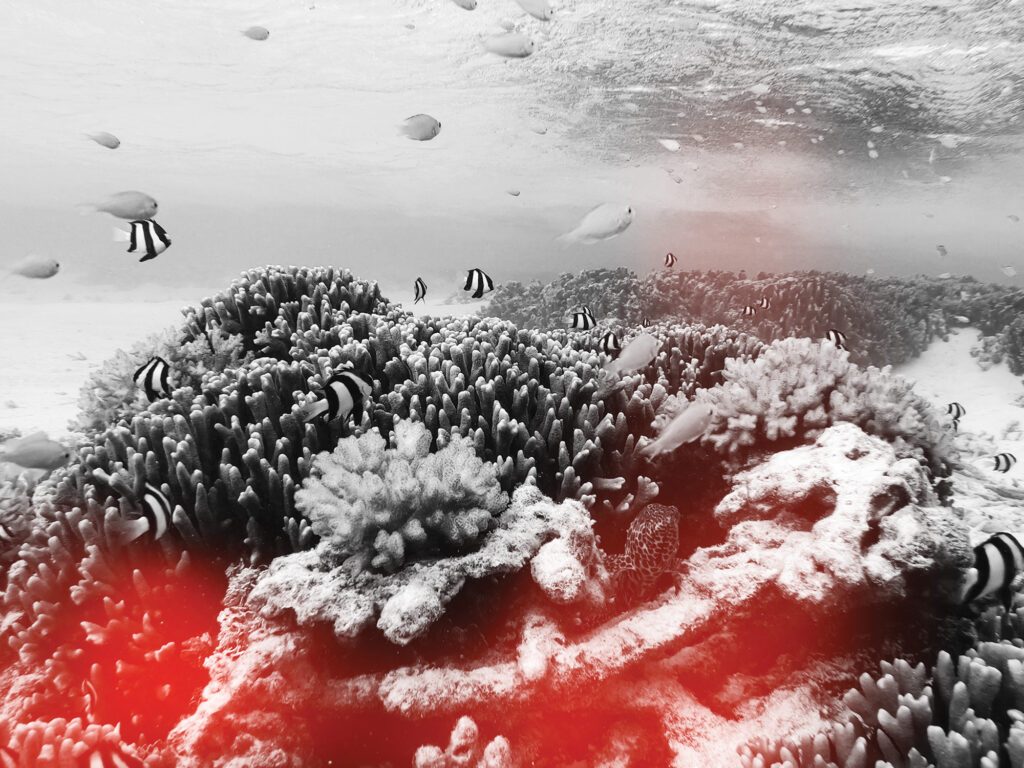

Coral is dying because of warming oceans.

According to one recent report, the astonishing pace of warming in the oceans is the greatest challenge of our generation. It’s altering the distribution of marine species from microbes to whales, reducing fishing areas, and spreading diseases to humans.

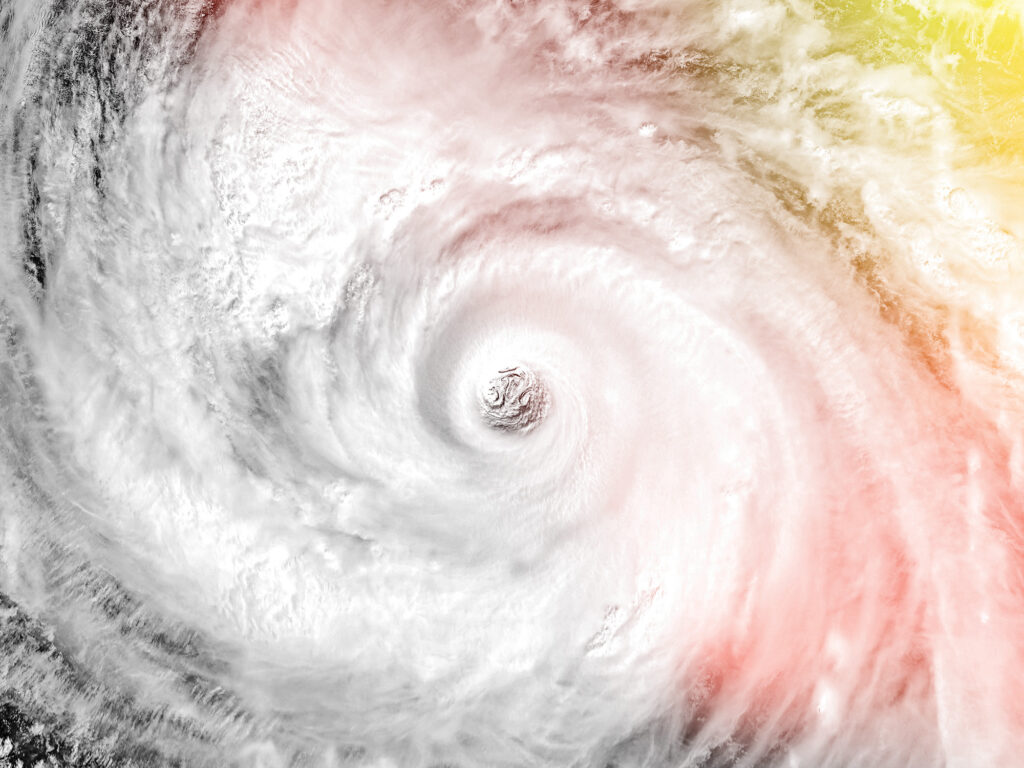

Warmer ocean temperatures and higher sea levels are expected to magnify their impact and intensity. Areasaffected by hurricanes are shifting poleward. This shift is likely associated with expanding tropics caused by higher global average temperatures.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, an increase in Category 4 and 5 hurricanes is likely, with hurricane windspeeds rising as much as 10 percent. Warmer sea temperatures also are causing hurricanes to be wetter, with 10 percent to 15 percent more precipitation from cyclones projected in a 3.6-degree Fahrenheit increase in mean global temperatures.

The timing of the cyclone seasons is an essential factor in voyage planning. One result of climate change is that tropical storms are now occurring outside of the accepted time frame. Although the official North Atlantic hurricane season continues to be June 1 to November 30, in the past 10 years, five of the 161 named storms occurred in May. The earliest among them was Tropical Storm Ana, which affected the southeast United States from May 8 to 11, 2015. The latest-occurring hurricane in recent years was Otto, which caused much damage in southern Central America between November 20 and 25, 2016.

More-active hurricane seasons are also expected in the eastern North Pacific—in the area between Mexico, Central America and Hawaii. The behavior of hurricanes here is similar to that of the North Atlantic, and the critical season, officially lasting from May 15 to November 30, is also lengthening. Among the 205 named storms recorded in the past 10 years, nine have occurred in May, four of them in the first half of the month. The earliest, Andres, occurred between May 9 and 11, 2021, while the latest, Sandra, struck between November 23 and 28, also in 2021.

These examples have a direct bearing on voyage planning. They show the importance of not arriving in the critical area before early December, and of leaving it before early May. The critical season should be considered to last from May 1 to November 30.

In the Northwest Pacific, the frequency and force of typhoons are also increasing, with some super typhoons having gusts of 200 knots or more. Typhoons have been recorded in every month of the year, with a well-defined safe season now a thing of the past.

Similarly, in the North Indian Ocean, the severity and destructive power of cyclones have also intensified. The trend in the Southern Hemisphere points in the same direction. In the South Indian and South Pacific oceans, the cyclone seasons last longer, and the frequency of extra-seasonal cyclones has increased.

I have been monitoring global weather conditions since the 1980s, and I’ve regularly surveyed long-distance sailors for more than 40 years. Most recently, I interviewed 50 sailors about their views on climate change and its effects on future voyages. Most of them are active sailors, with more than half having completed at least one circumnavigation.

In 2018, a similar survey found a few who had doubts about the seriousness of climate change’s effects, but this time, with one exception, everyone agreed that the threat is serious, not only to future voyages, but also to mankind itself.

Some sailors also expressed other concerns, such as overfishing, widespread pollution, and the threat that rising sea levels pose to tropical atolls and low-lying areas. Another area of concern is the change in attitudes toward visiting sailors. This was highlighted during the pandemic, when many countries imposed restrictions that forced visiting boats to stay at anchor for long periods of time. There were several reported cases of hostility toward sailors from authorities and local people, even in areas where previously visiting sailors were warmly welcomed.

I also asked these sailors whether climate change would influence their decision to plan a world voyage now. With only one exception, they said that while they were aware of the considerable effects, they would still leave on a long voyage. Basic safety measures would include arriving in the tropics well before the safe season, and allowing a safe margin by leaving before its end; avoiding the critical period altogether; monitoring the weather and having a Plan B; and making sure their insurance company agreed with any plans they made to leave the boat unattended.

Ric De Cristofano, director of underwriting at Topsail Insurance in the United Kingdom, tells me that climate change is likely to be the main topic for insurers throughout the next decade. Internal models at these companies are forecasting higher frequency and severity of hurricanes, and even of lesser weather events such as electrical storms.

“The impact on boat owners planning to go cruising will be both direct and indirect,” he says. “The former is likely to include increased coverage restrictions along the lines of no Caribbean windstorm cover, and for such risks to be rated higher by insurers. As for the latter, the insurance industry is preparing itself for large and catastrophic insurance events to become more frequent, which ultimately will lead to cost increases across a whole range of services.”

The sailors whom I surveyed all stressed the even greater importance of having reliable access to weather information in this world of changing conditions. PredictWind is the most popular source of weather data and forecasts for sailors on ocean passages. Nick Olson, business development manager at PredictWind, says that, yes, weather events will become more extreme, “but that is the type of event we aim to avoid already.”

PredictWind will have new tools aimed at extreme weather coming online soon, he says: “One will alert you when there are certain factors, which could produce extreme weather that would trigger potential thunderstorms. Another extreme we might see is having more light winds. Our departure-planning and weather-routing tools both rely on forecast modeling, which will adapt to climate changes and predict the expected conditions like they do now in producing the short-term forecasts.”

One visible result of climate change is the increasing number of sailors heading for high latitudes, to capitalize on more-favorable polar conditions. I benefited from this myself with the successful transit of the Northwest Passage in 2015, which was possible as a direct result of climate change.

Voyages to Antarctica fall into a similar category, and no one is in a better position to comment about that region than Skip Novak, widely considered the world’s authority on high-latitude sailing. He sees weather and sea-ice concentrations changing.

“For those of us who sailed regularly in the Southern Ocean from 40 years ago, the consensus of colleagues is that sea conditions seem much more volatile than before,” Novak says. “One theory of substance is that in the Southern Ocean, the westerlies are being compromised by winds pushing through this band from the north, certainly more often than in previous decades. This causes the steady, long swells that we have formerly experienced to be less consistent with more washing-machine-like conditions.”

It’s tricky to postulate on sea-ice concentrations for navigation. Novak says that for sure, temperatures on the Antarctic Peninsula have spiked from 40 years ago, but this does not necessarily mean less sea ice in any given year. A cold winter and lack of strong winds from spring into summer will leave inshore waters ice-choked, sometimes into late January.

“It remains, as it has always been, the luck of the draw on where you can go,” Novak says.

Some of the more-experienced sailors in my survey, such as Pete Goss of Pearl of Penzance, a Garcia Exploration 45, stressed the importance of “having a well-built, strong boat that you have confidence in and that would be able to stand up to the weather, and ensure you survive it.”

Retired French Admiral Eric Abadie, currently on a world voyage on Manevaï, a vintage Garcia Nouanni 47, was more concerned about “the impact of climate change in the countries we plan to visit, and even more by the resulting political instability caused by it. For me, the answer is very simple: It’s on the water that I am truly happy. And that will not change.”