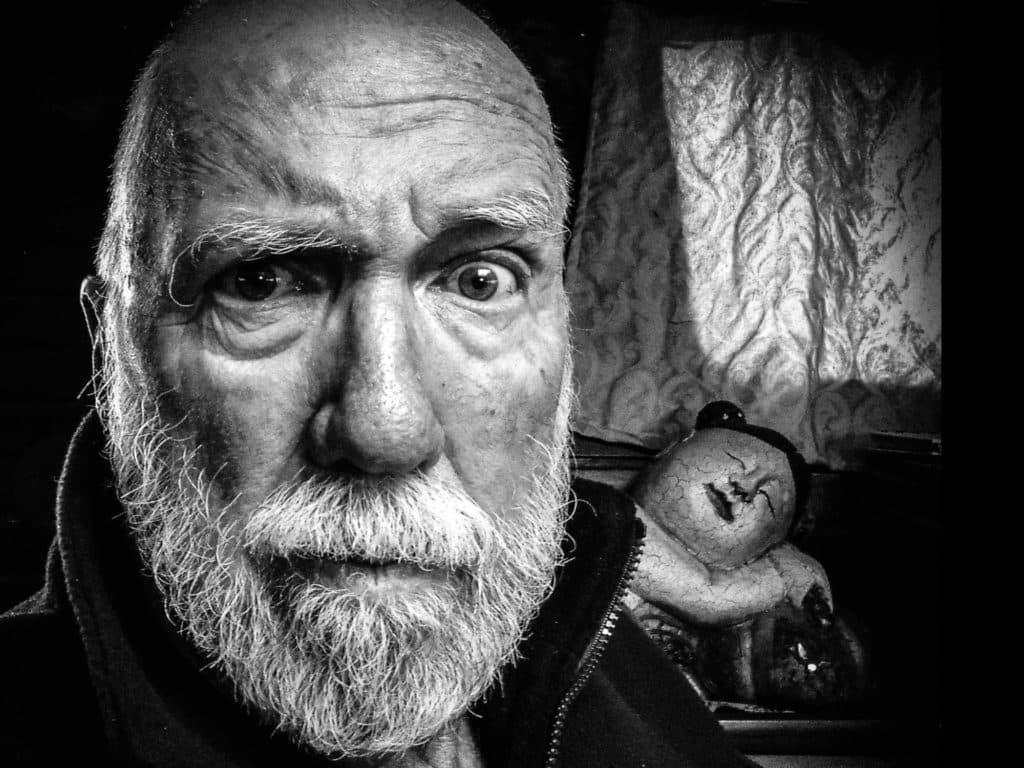

The most important sailor in my life was my father. The most important sailor in his life was a wood butcher called “Chips” who worked as a handyman at the Lutheran orphanage in Chicago where my father was incarcerated a hundred years ago. After a day of replacing lightbulbs and sweeping up the halls, Chips would retire to a modest toolshed on the grounds—and construct small sailing craft. My father, while plotting his escape, was attracted to the sounds of the caulking mallet, the wood plane, the brace and bit, the adze and the draw spoke. He loved the slap of the sandpaper and the grunt of the shipwright.

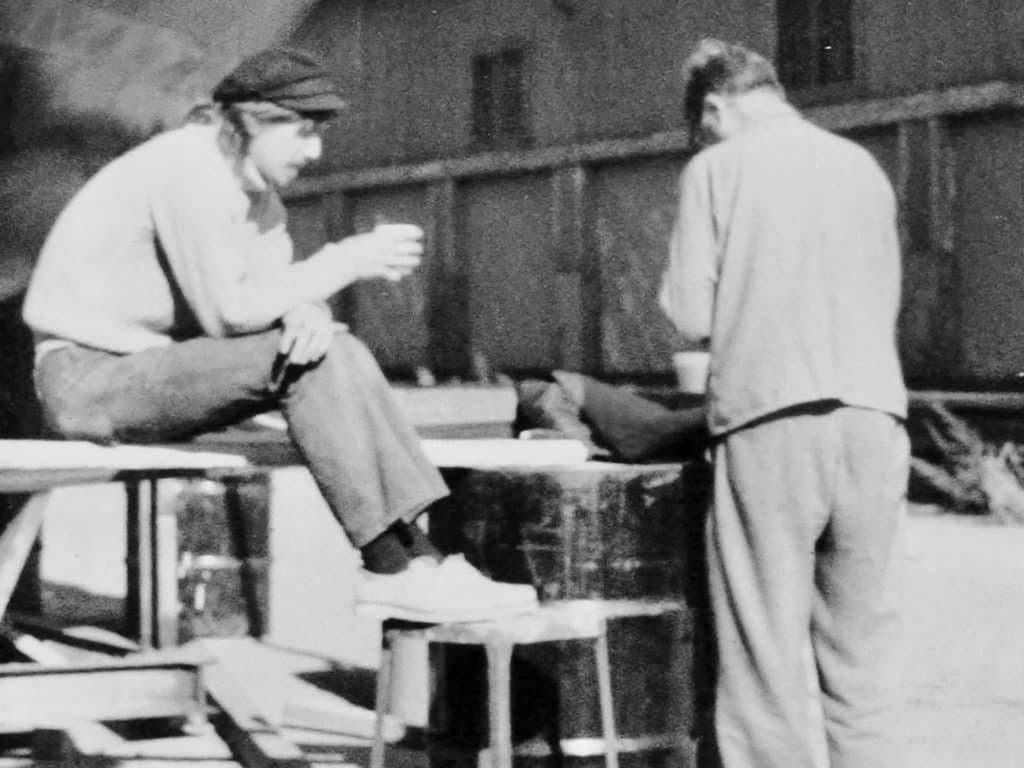

My father stood at the door of the boat shed, doe-eyed—and then scurried in at precisely the right moment to hold the end of a wobbly plank, help soap the No. 16 silicone bronze screws, or assist in peening over the heads of bronze drift bolts. Like most shipwrights, Chips muttered about the sea as he marked off his planks, shaped his horn timbers, and angled the edges of the garboard just so.

Timing is everything. My father longed to be free. There was then, and there is now—no freer place than the sea.

Chips gained an apprentice; my father gained a mentor. About a year in, Chips told my father to brush off the sawdust, and he took him to a library and introduced him to the librarian as “Sailor Jim.” The librarian fed my father a steady stream of books by such seamen as Irving Johnson, Alan Villiers, Frederic Fenger and Eric Newby. He read every book about boats in the Chicago library system—twice. Only once did he ask for a nonmarine title: a book about forgery.

While my father was a completely open and honest man who always told the truth and never cheated, he held no allegiance to the rules of others. He simply ignored them—a reason, perhaps, that he found the sea and her harsh-but-fair rules so enticing.

In the orphanage, after a certain age, a kid could get a pass to visit relatives if the family jumped through a lot of bureaucratic hoops. My father had no family, had no hoops to jump through. So, after lights out, he’d work with his flashlight, paper and pens, and was soon allowed to visit his North Side relatives to help acclimate and integrate him into polite society.

But the only society that interested Sailor Jim was the brethren of the sea. He’d stand patiently by the dinghy racks at the Chicago Yacht Club. When a boat owner would attempt to drag his tender down the beach, Jim would lend a hand. Everyone thought he was another member’s son. “Do you know anything about varnishing?” one owner asked.

“A bit,” Jim replied.

Yes, timing is everything.

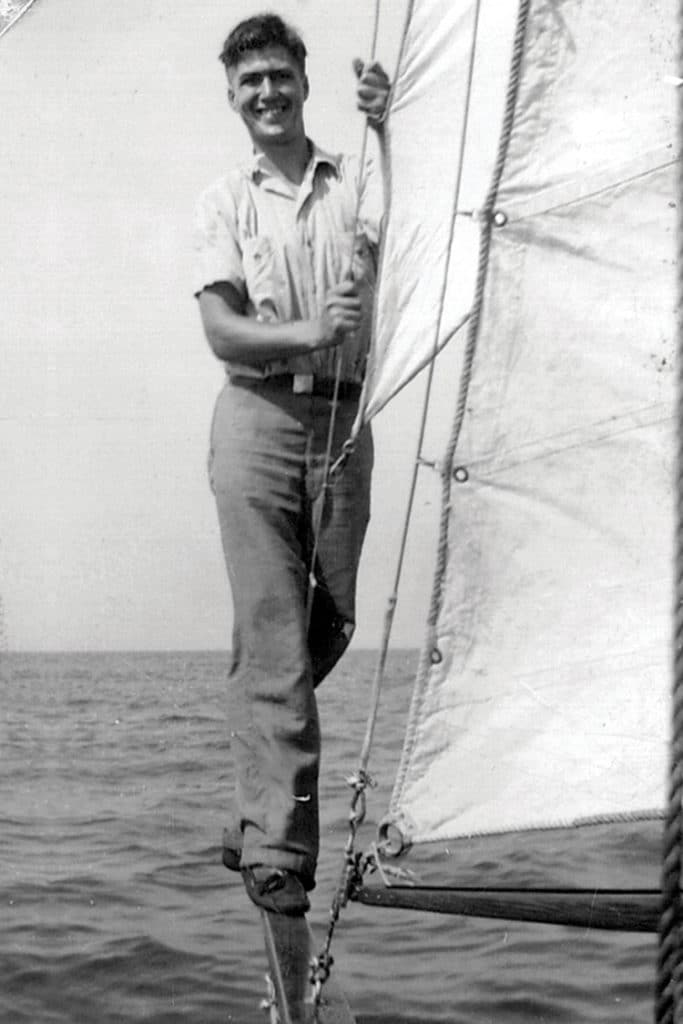

Refinishers are always sought around a yacht club. Jim was soon popping open varnish cans on a 68-foot gold-plater designed by John G. Alden. He did such a good job with his brush that the wealthy owner invited him out sailing. It wasn’t long before he was skippering the foredeck—and studying celestial navigation on the side.

One day, Jim invited a friend from the orphanage to accompany him on a race. The race went well, and Jim was proud of all the smooth sail changes. On the bus ride back to the orphanage, his buddy slyly pulled out a pair of kid-leather gloves and said: “Lookie, Jimbo! They were just sitting on the table down there in the boat. Nobody was around, so I nicked ’em!”

My father couldn’t believe it. He grabbed the expensive gloves, rushed off the bus, and managed to get back to the yacht club just as the owner was climbing into his Bentley. He returned the gloves, explained the situation and apologized profusely—ending with: “Well, I made a mistake, sir. I invited somebody aboard that I should not have. You trusted me, and I didn’t live up to that trust. So, I guess I’ll see you around. And again, sorry.”

“Now, now, Jim,” the owner said. “I invited you aboard because you could swing a brush—and I kept you as part of the crew because you were a hard worker and a quick learner. But frankly, I had no idea if you were a good person or not. Now I know. The key to the companionway is on a hook inside the quadrant box. I want you to treat my vessel like she’s your own—and keep that varnish glowing.”

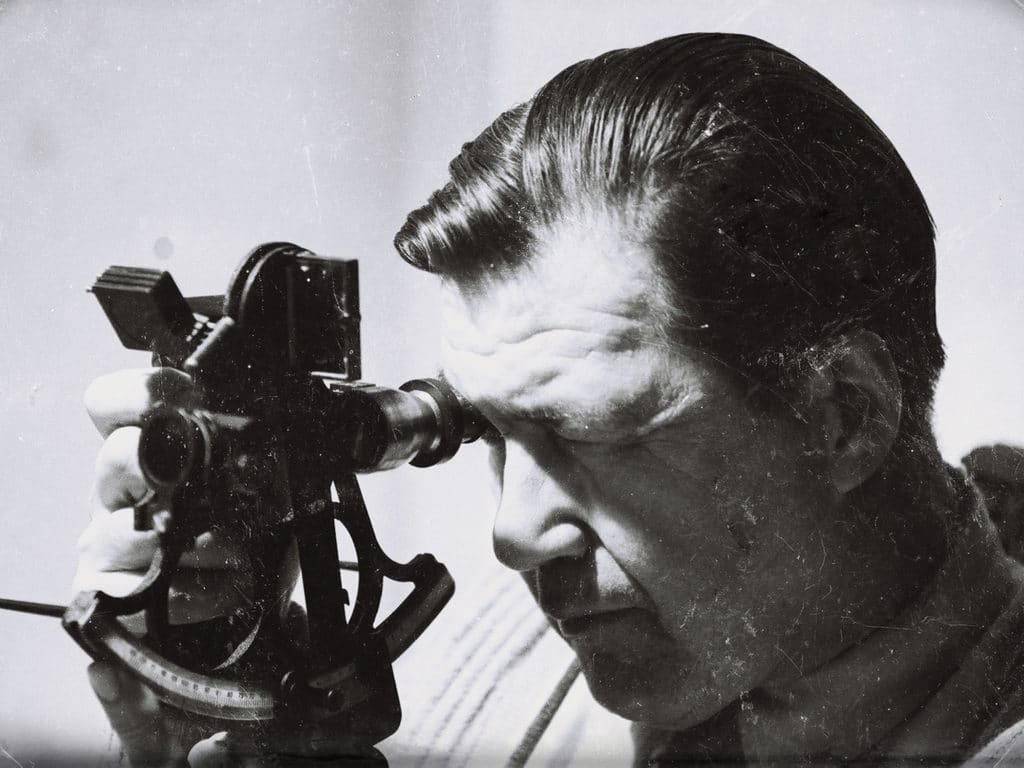

The big Lake Michigan race was, both then and now, the Mackinac. My father, always good with numbers, acted as backup navigator at first, and then as the main navi-guesser. Evidently, he did all right; he was soon shooting the sun from the decks of vessels throughout the Great Lakes, and then all along the East Coast.

As soon as he managed to spring himself from the orphanage, he purchased the 22-foot Dorothea for $10—$5 for the boat, and $5 for the team of horses to drag her to a vacant lot. Everyone on the South Side said “that fool’s boat” would never float. It did. It even won a couple of races. A Chicago Yacht Club member lent him an expensive mooring right downtown, within sight of the club. He met a local girl at the Rexall’s soda fountain (a hotbed of seduction in those quaint days) and drove her down Lake Shore Drive as he said nonchalantly: “That’s my little carvel-planked sloop out there—the black hull. Her name is Dorothea.”

“Lovely,” said my mother-to-be, who vainly wasn’t wearing her eyeglasses at the time and couldn’t even see the dashboard.

A few months later, he popped the question at the Butter Burger drive-in: That’s right, he asked her if she’d consider living aboard.

“But isn’t your boat too small?” Marie asked, bewildered. “Can you really do that? With kids? It sounds crazy, Jim.”

“Yes, Dorothea is kind of small,” he agreed, “but I’ll sell her. I’ve got my eye on a lovely little 36-foot Friendship sloop that pounded on some rocks off St. Joe and—”

“Well, I guess I could try,” Marie said, all starry-eyed.

As children, we must have heard this story of their unusual courtship a thousand times.

“At the time, I knew. Oh, I knew. I knew I wanted to have his babies—ashore or afloat.”

Father had enjoyed his time with pen and ink. He was good at calligraphy. And he liked to draw. So, he naturally slid into sign painting. Soon, half the transoms in Chicago displayed his work.

“No need to haul,” he’d say from his paint-splattered dinghy. “I’ll just pick a day with less than 3-foot seas, no rain and not much adverse current.”

And he raced every race in the Great Lakes and beyond. He purchased the Friendship sloop in partnership with a dentist called “Doc Zic” (if my memory serves). Upon its sale, the good doctor took every penny he invested (and not a penny more), thus giving the huge profit entirely to my father, who immediately opened Goodlander Signs on Englewood Avenue.

But the winds of war were blowing across Europe. For America to win, the country desperately needed celestial navigators with lots of practical, hands-on experience at sea. Soon, my father was living in a posh apartment in the French Quarter of New Orleans and teaching. There was only one problem: He’d joined the service to stop the fascists and save freedom, but his commanders would not allow him to leave his desk. They said his teaching skills were too valuable.

Damn!

He consoled himself by hanging out at the yacht club on Lake Pontchartrain, and by racing from Galveston, Texas, to Key West, Florida. One day, he overheard that his base commander was in a big jam. He’d been ordered to get three ships from Cozumel, Mexico, to New Orleans by a certain date. However, the commander had failed to do so, and now time was growing too short. And, because of the red tape, well, it was almost impossible to accomplish now.

“No problem, mon!” my father said as he took a gaggle of drunken bilge rats out of the yacht-club bar. They had all three ships in New Orleans within the week.

His reward was an officer’s slot aboard a ship heading for the Pacific theater. There was only one problem: The skipper of the ship was old, frail and timid. This skipper had been asked to serve his country, and had answered the call nobly and to the best of his ability. But as the war wore on and his mental and physical health deteriorated, he was increasingly unable to perform his duties. My father attempted to help out as much as possible. They became close friends. Finally, they were ordered to San Diego to reprovision before heading out to patrol the western Pacific.

As they approached the submarine net in San Diego, the elderly skipper was in his cabin, fussing, for a long time. Finally, he came onto the bridge and took the conn. He looked strangely dapper—freshly scrubbed with a whiff of cologne. As they got closer to the net, my father said softly: “I think we’re on the wrong side of that mark by the tugboat. We should go to port of it. I think we should leave it to starboard, sir.”

The skipper didn’t move. He stared straight ahead. The tension on the bridge skyrocketed. Finally, the captain said shakily, “Enter it in the log, Mr. Goodlander.”

This meant that, officially, my father would be accusing the skipper of making a major mistake and worse, sticking with that mistake after being corrected by a fellow officer. Father didn’t want to do that.

“Do as I say,” the skipper said harshly.

My father did so—and was barely finished with his log entry before the ship plowed into the submarine net and entangled its prop. Without a word, the skipper left the bridge and returned with his suitcase, which was already packed.

While awaiting the gangplank to be lowered, he said wearily, “That’s it for me, Jim.”

Back at the shipyard, peace was declared. America had won. As all the horns started to blow. My father tossed his officer’s hat high into the air and walked out—never to return to organized discipline in any form. He’d done what he felt he had to do to protect freedom and defeat fascism. Now none of those silly military rules applied.

Back in Chicago, Goodlander Signs grew to three trucks, numerous employees, and a large number of block-and-tackle stages to paint signs on tall buildings. Jim plowed all his money back into the business. While he was broke, the future was bright. His two daughters were growing up straight and true; his new son was gaining his sea legs.

To amuse himself on long winter evenings after the kids were asleep, he’d pen stories for Yachting magazine about navigation and seamanship. My mother would hunt-and-peck over her rose-scented novel.

Every morning, he’d drive over a bridge on the Calumet Sag Channel and look down at a lovely 52-foot Alden schooner named Elizabeth. He’d raced against her many times. She was hauled out on a railway car. The graceful, carvel-planked wooden vessel, constructed in 1924 by Morse Brothers in Maine, was going through a major refit. All her hardware was off, and her rig was down. Off-site mechanics were working on her 25 hp Scripps gas engine and, not being sailors, had left some oily rags.

That night, Elizabeth partially burned—mostly her main cabin and deck amidships. Her owner, Lynn Williams of the Chicago Yacht Club, wanted her declared a total loss, but the insurance company wasn’t too sure. In order to free up the railway car to haul other boats, the Elizabeth was relaunched and, a few weeks later, sank at the dock.

The insurance company then declared her a total loss. The dockmaster wanted the use of his dock ASAP. And at this precise moment, my father came fishtailing into the shipyard in a cloud of dust, waving a hundred-dollar bill that he’d kept tucked in his wallet for exactly such a happy occasion. He screamed at the top of his lungs: “I’ll buy her! Right now! As is, where is!”

Yes, timing is everything. Fortune always favors the bold. Here, finally, was his escape pod. They’d never be able to lock him up again.

And that is the story of my childhood floating home—the noble vessel I grew up aboard for the first decade of watery life, and the twin ideals of hard work and independent action that so emboldened me from an early, salt-stained age.