This definitely wasn’t the best start.

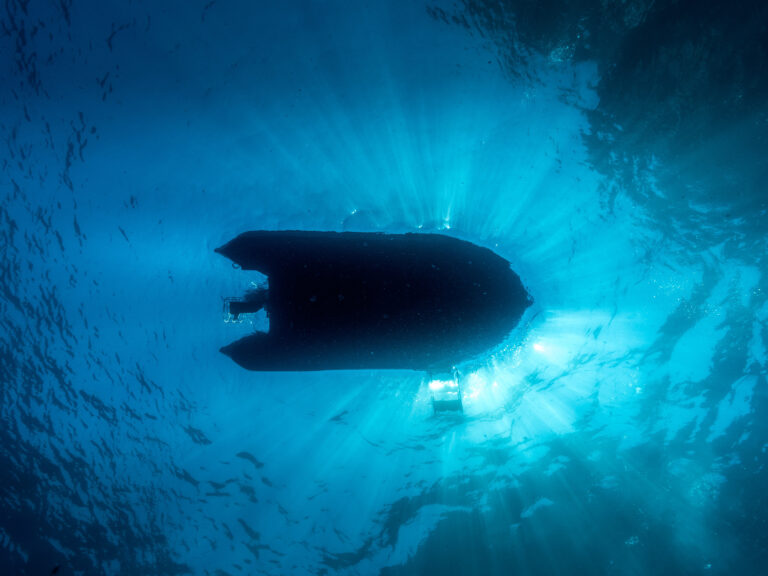

Our plan was to deliver the Jeanneau 53 Kaimana across the Pacific from San Diego to Honolulu for a friend and client, Michael Prescesky. I found myself drifting in a tiny inflatable, in the Pacific, a few miles off San Diego.

The dinghy engine had just spluttered to a stop, and the small inflatable was rocking gently in a light sea breeze. It was eerily quiet. I watched Kaimana sail away under its new pink spinnaker, against a fine backdrop of the distant San Diego skyline. To my right, the hills of Tijuana, Mexico, shimmered in the sea haze, dead downwind.

While taking photos of the boat during our sea trial, I had gotten carried away (no surprise there) and quickly used all the gas in the tiny, built-in fuel tank of the 6 hp Yamaha outboard. This now seemed like a significant lapse of judgment.

I pulled out my phone and called my crew, longtime sailing friend Tracy Dixon, aboard Kaimana. A retired US Navy explosive ordnance diver, Tracy is predictably methodical. He hates surprises. And yet, he has inexplicably done several ocean crossings with me.

My phone erupted in a burst of static, followed by a recorded voice saying something in Spanish like, “Bienvenidos a Mexico.”

Tracy and I knew this boat well, having delivered Kaimana from Hawaii to the Pacific Northwest. While waiting for my two nephews, 24-year-olds Rowan and Quinn, to arrive from work, and in Rowan’s case, a college graduation, Tracy and I had decided to go on a shakedown sail and test the new spinnaker.

For our sea trial, I’d enlisted the help of some veteran local racing sailors, Lani and June Spund. Tracy and I had met them while searching for a used spinnaker for our downwind run back to Hawaii. Having owned and raced a series of ultralights like the Santa Cruz 50, Lani had a treasure trove of sails and gear, but he didn’t have the sail we needed. Regardless, we immediately struck up a friendship with the delightful couple. Lani felt that sailing to Hawaii with my two nephews was simply “a gift.” They volunteered to come along and help with the shakedown cruise because Quinn and Rowan hadn’t yet arrived.

I stood in the dinghy, hoping that Lani and June would be able get the sail down with Tracy, then turn back for me in the waning daylight. Otherwise, it would be bienvenidos a Mexico for me.

My first thought was: And you don’t even have your passport.

Kaimana, now on a beam reach and perfectly trimmed, was disappearing at an alarming clip under its pink sail, sans the skipper. Until now, I’d been excited that I’d finally found that crispy, nearly new spinnaker for our downwind crossing at the local Doyle loft through its fantastic SailM8 resource for sailing gear. By the look of it, the sail was a perfect fit. Too perfect. It was flying beautifully, pulling the boat away from me at a pace of around 7 knots.

Preparing a boat for a Pacific crossing is never easy—even this boat, a recently surveyed Jeanneau 53 from 2017.

I was a little uneasy being so far out at sea in a 10-foot inflatable, but the situation wasn’t life-threatening. I was more embarrassed that I’d left the boat and failed to return.

Meanwhile, on board Kaimana, Tracy had begun methodically untangling the spinnaker snuffing sock, which, after a few jibes, had become tangled. As they sailed on, another yacht appeared to leeward, all smiles and cameras pointed at the pretty spinnaker, but also blocking the route downwind that they wanted to douse the sail. They finally got clear, doused the sail, and motored back to me. By this time, they’d covered several miles, and just managed to find me.

I apologized sincerely for making the crew scramble. Tracy, to his credit, said it was great practice for a man overboard. The lesson was that under spinnaker, a man overboard could be recovered only if the boat were immediately stopped. Sailing away while messing with the sail wouldn’t be an option.

At 6 to 8 knots, the boat covers a mile in less than 10 minutes. At even a fraction of that distance, with intervening seas, a swimmer would not be visible. I resolved to keep the crew safely aboard. Failing that, if anyone went overboard, we’d change course immediately to stop the boat, whether luffing up into the wind or heading dead downwind. The spinnaker could then be tamed or depowered by blowing the tack, then quickly snuffed or dropped on deck.

Of course, all crew would have an AIS beacon attached to their inflatable harness. Far offshore, the AIS beacon is the only device that can alert your own boat, certainly the closest vessel, and is your best chance of a timely rescue. It was a given that the dinghy would stay stowed while underway.

Preparing a boat for a Pacific crossing is never easy—even this boat, a recently surveyed Jeanneau 53 from 2017. I had already delivered Kaimana across the Pacific once, a passage to windward, from Hawaii to Victoria, British Columbia. Michael then sold it, but later decided that he just couldn’t live without it and purchased it again. In the meantime, the boat had mostly sat idle in its berth.

I spent weeks preparing the boat. And I still had unexpected issues at sea. More about those later.

Hundreds of jobs presented themselves, from the top of the mast to the bottom of the keel. We flew in from Hawaii, arriving late in San Diego. I woke up ready to dive right in, and pumped up a glass of water with the foot pump at the galley sink. While downing it, I realized that I was actually drinking salt water. San Diego Bay salt water, in fact. Where the military runs ships, dry docks and bases. The foot pump, I remembered, has a handy Y valve to switch from salt to fresh water. Somehow, I survived without getting sick. Long-term effects are yet to be determined.

The best thing about Shelter Bay was Roberto’s Taco Shop, which stands out even in a city full of great Mexican food. We loved this food so much that we became a fixture there. We met the owner and his family, most of whom worked at the shop. They were openly curious about our story, wondering how we could sail “all the way to Hawaii.” We found the family hardworking, kind and generous. Basically, your typical Mexican immigrants. When I showed up just after closing time one day, they sent me back to the boat with a chili verde burrito, on the house. Unable to live without Roberto’s food, we ordered three huge trays of frozen meats for the crossing: carne asada, chili verde and al pastor. We even brought numerous bags of the heaviest, most lard-filled and delicious handmade tortillas ever made.

Our weather window showed a few days of headwinds, followed by developing high pressure that would send us all the way to Hawaii, with trade winds on our starboard quarter.

My two nephews arrived. Both of them have crossed an ocean with me once or twice. Quinn, my brother’s son, had just graduated from the University of California at Santa Barbara with a degree in geography. A keen surfer, Quinn had some free time before heading out to Indonesia to coach resort tourists on how to surf some of the best waves in the world, a posting that made his uncle a bit jealous. Quinn is an instinctual and physical learner, the kind of sailor who feels the boat and sails it fluidly, without evident effort.

Rowan had also just graduated, from the University of California at Berkeley, with a degree in architecture. After two Atlantic crossings with me, and time at a college sailing club honing his skills, Rowan can usually balance the boat in that sweet spot between too high and too low. I can sleep when either of these “kids” is on deck, which in fact might be the highest form of praise from a captain. I also had Tracy aboard, who has done even more crossings than these two. A few years older than I am, he retired as a senior chief from the Navy, where he spent his career defusing bombs in underwater demolitions. He always offers to take the worst job on the boat. After several tours in wartime Middle East, his usual response to any hardship at sea is to say, “Oh, yeah, I’ve seen much worse.” For me, this was the dream crew, and they all got along well. Never a cross word was spoken.

Despite the fact that the Pacific High hadn’t quite filled in and we would have to beat to weather for a few days, it was time to go. We’d worn out our welcome at Shelter Bay Marina with the most miserable harbormaster I’d ever met. For some reason unknown to us, she’d decided that she did not like us. After she’d threatened to come down and physically cut equipment off the boat, claiming it belonged to another client, I’d felt it was time to go. Sailing to windward wouldn’t be so bad in comparison. That is the beauty of a sailboat: You can always just sail away.

San Diego was surrounded by the usual coastal low clouds when we motored out of the bay. The wind was light and unreliable. We knew we’d have to get clear of Point Conception before we’d find the northwesterlies.

As we motorsailed out into the Pacific, our AIS and radar showed a naval vessel on our starboard bow. It seemed to be slowly altering course to pass behind us. Tracy identified it as an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer as it passed us to starboard on a reciprocal course. A series of helicopters flew overhead, dropping large parcels into the sea off our port side.

Suddenly, the destroyer began firing 5-inch projectiles into the sea at these parcels, right across our wake. It was a spectacle. I was heartily glad they’d let us get well past before opening fire.

The wind began to increase late that night in fits and starts as we sailed out into the unobstructed coastal northwesterlies. We passed the shoals at the famous big-wave surf spot Cortes Bank, about 100 miles off the coast near the Channel Islands, due south of Point Conception. We began to hit speeds of 10 knots, and soon had double reefs in both the main and jib. At 7 to 8 knots, the boat was working in the seas and taking occasional waves over the bow. Rowan ejected his chili verde burrito dinner over the rail.

Before daybreak, I heard footsteps from my bunk in the forward cabin. Quinn, the surfer, had noticed that the tail of our spinnaker tack line had washed loose where it was coiled at the bow. Most people would have left it, but being Quinn, he was going forward to secure it.

I peered up out of my hatch. Quinn seemed a bit nervous, which I realized had nothing to do with the seas. He wasn’t sure how I’d react to this adventure, as captain. I could tell he was fine. He was balanced on the foredeck, he was properly tethered to the boat, and he kept an eye on the seas while riding the boat like an oversize surfboard.

He was the one who volunteered for the most challenging jobs. Later in the voyage, when the wind got light, it was of course Quinn who volunteered to dive down to remove a loop of drifting fishing-net rope that had fouled the prop. Emerging with rope in hand, he was the spitting image of his father, Alex, when he was in his 20s: capable, fit and pumped up for any adventure.

Quinn was also the keenest fisherman aboard, diligently setting the lines every morning before sunrise. We used my trusty squid jigs, weighted with lead on heavy 300-pound-test monofilament hand lines, with oversize bungees. We had little luck for a week. Quinn was disappointed. “Uncle Tor,” he complained, “this is the worst fishing trip I’ve ever been on.”

Sadly, it was just after Quinn had gone below for a nap that we hooked a 6-foot-long billfish. I had deliberately wrapped the fishing line backward around the windward sheet winch in the cockpit so that the spinning winch would alert us if we had a strike. Suddenly, the winch spun wildly, then stopped. I pulled in some of the line, but it was slack—no fish on. We could see a large gray shape underwater following the lure. Knowing that billfish first hit their prey to stun it and then come back to swallow it, I released the line in my hands all at once. The fish swallowed the lure. Sheeting out the sails to slow the boat, I brought the beast up to the transom with some effort, where we gaffed it and brought it aboard.

Until we managed to secure a line carefully around the bill of the flailing fish, there was a real threat of serious injury from the whipping bill, hook and gaff. This far from medical care, we did everything carefully. To our amazement, Quinn slept through it all. When he reappeared on deck, I told him we had “caught a little fish” and sent him to look on the transom, across which the beast was stretched.

When he said he didn’t feel well enough to stand watch, I knew he was incapacitated.

He was happy that we had a fish, but obviously, he had wanted to be the one who caught it. Quinn wasn’t disappointed for long; a day later, he caught two large wahoo on his morning watch. The ocean provides.

Unfortunately, though, Tracy had apparently contracted a case of COVID in San Diego while we were provisioning. Fever and chills began just as we encountered open ocean seas. He developed an alarming, deep cough. When he said he didn’t feel well enough to stand watch, I knew he was incapacitated.

Luckily, we had four crew, and there was some slack built into our watch schedule. The schedule had each crewmember keeping a four-hour watch, with me, the captain, as second watch stander and backup in case of sail changes, ship avoidance, or anything else. I hadn’t scheduled a watch for myself, which kept me ready at any time that I was needed on deck. This was such a time, and I was able to stand Tracy’s watch, with no change in the schedule for anyone else.

After two nights of this, Tracy miraculously appeared on deck and began sharing his encyclopedic knowledge of the history of civilization, so we knew that he was pretty much back to normal.

Our main concern at sea was large vessels, so we kept a good watch. We encountered a number of container and tanker ships off the California coast. On two occasions, large container vessels changed course unpredictably and erratically, making it nearly impossible to decipher their intentions. A quick VHF radio call to the bridge got their attention, and we were able to avoid them.

Having seen this before, the experience got me wondering what would cause them to drive like drunks. I later asked a friend who captains a container ship for Matson. He told me that these ships have trouble slowing down. Much as with our smaller marine engines, they’re vulnerable to carbon buildup when run at slow speeds, and they’re designed to run at nearly full rpm, except when maneuvering, which is maybe 5 percent of the time. When waiting for a berth, they’ll often zigzag, slowing down only minimally, to kill time. They also perform regular steering tests and man-overboard drills.

We were well into the crossing when we found out that our water supply was contaminated. The water had appeared fine at the dock, but once it all got stirred up offshore, a nasty white film clogged the filters and water pump. Changing water tanks didn’t help. We had already added vinegar to the tanks, but this didn’t help. The white slime remained. I tested two water samples in clear bottles, adding bleach to one and vinegar to another. The bleached water was clearer, but the white slime remained in both.

Fortunately, we’d had the foresight to stow a good amount of bottled water under the floorboards in case of contamination like this, or a leaking tank or water line. Immediately taking stock of our bottled water, I came across a large trove of water bottles deep in the bilge. We had stowed these in 2018, when we had delivered this same boat from Hawaii to Victoria, British Columbia. Complete with labels saying “Aloha Water,” this unexpected gift meant we would have a good backup of clean water to make it to the Aloha State.

Our next unhappy discovery was oil in the bilge. It started as a small puddle, but as we puzzled over its source, it began to accumulate faster. Finally, we isolated the source to the generator, which we’d had serviced in San Diego before leaving. The mechanic had failed to tighten the new oil filter adequately, and oil was spraying out in increasing volume.

Unfortunately, the generator was installed under the transom, and the only access required removing the heavy transom cover, exposing the boat to following seas. We discussed our options. We had our new pink spinnaker flying and were making good speed in relation to the relatively moderate following seas. There was still the risk of being overtaken by a wave at the wrong time.

Tracy, ever the careful, methodical bomb tech and our voice of reason, advised against tackling the issue so late in the day. Quinn, my go-getter nephew—who coincidentally had done a lot of the oil cleanup—wanted to go for it and stop the leak.

I made a snap decision to go ahead and disassemble the transom. Tracy located the perfect filter wrench, and I found myself fully harnessed in, literally dragging my feet in the wake as I leaned over the generator, tightening the fuel filter as the boat surfed along under spinnaker in the golden light. I got it done, and just as I dropped the heavy transom cover back into place, a wave slopped aboard, harmlessly. It was a win for the crew.

The Pacific High filled in slowly, bringing the welcome puffy clouds and brilliant blue skies of trade-wind weather. The seas increased in size, and we began surfing down waves to 12 and even 14 knots under main and genoa. Squalls increased, usually looking more ominous than they were.

I awoke one night in the forward master cabin, feeling the boat heeling a bit farther than normal, ripping downwind. Donning my self-inflating vest with a harness, tether and AIS beacon attached, I stumbled on deck to find Rowan on watch, enjoying some active sailing as the boat careened downwind. It was still in control, but only just. Being a fairly conservative sailor, and this being a delivery, I mentioned that we might want to reef.

“Oh, no need,” Rowan said. “It comes and goes.”

“OK, Rowan, but you know where I am if you do need to reef,” I replied, reluctantly going below.

Not half an hour later, I felt the boat heel rapidly. Too much sail. I rushed back on deck in a pelting rain squall to help Quinn, who had just taken over the watch from Rowan, reef the sails. We squared everything away quickly without issue after a few tense moments.

According to Quinn, Rowan had pointed out a number of squalls in the moonlight before heading down to his warm, dry bunk. He said Rowan had joked: “Captain wanted to reef, but I told him to f-ck off.”

Of course, Rowan became the object of some friendly mockery for a few days after that, but we forgave him. I never thought being the captain and the uncle at the same time would be easy.

Rowan made up for his transgression by somehow baking a spectacular peach pie, which followed a luscious roasted chicken with potatoes for our halfway party. We’d settled into a rhythm, adjusted to our watch schedules, overcome a few challenges, and made it halfway across an ocean.

Even the dreaded squalls seemed less fearful and more beautiful with their deep purple-blue hues and towering clouds.

Things didn’t seem quite as overwhelming, the goal was in sight, and even the dreaded squalls seemed less fearful and more beautiful with their deep purple-blue hues and towering clouds.

The trade-wind conditions made for some spectacular scenes as the boat surfed down deep blue waves under brilliant sunny skies and dark squalls. I concentrated on flying my drone, skimming the wave tops and trying for lower angles that showed how the boat was surfing down the waves.

I’d just gotten some fantastic images of the boat surfing at 12 knots in big seas when the inevitable happened: The $3,000 drone flew straight into a wave.

It was lost forever, along with its precious images. I tried to remind myself that I’d already downloaded some good images, and I still had a tiny backup drone that could be pressed into service for the rest of the voyage.

When the wind moderated a bit, we began to see marine debris: large plastic barrels, lengths of fishing rope and pieces of fishing nets, some quite extensive. There was more debris than I’d ever seen in numerous Pacific crossings, and we began a constant refrain of “there goes another piece.’’

As most cruisers are aware, this is what’s known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which is actually a collection of items suspended in the water column of the North Pacific Gyre. It is not the more-sensational “floating island twice the size of Texas” that some people claim—not to minimize the problem of marine plastics at all, just to be honest about it here.

Quinn was fortunate to watch a setting full moon, balanced on one horizon off the bow, with a rising sun in our wake, and no soul but him to witness it. From his reaction, I’d guess the young man won’t forget that experience.

The boat rolled considerably in the steep seas, but after nearly two weeks at sea, we just rolled with it.

We had to dive down to free our propeller frequently while sailing through this area, usually removing a length of fishing net or polypropylene line. Normally I’d be the one to dive, but with Quinn aboard, it made more sense to send him down with a safety line while I made sure the boat was stopped. The passing on of knowledge and roles is a big part of our family sailing lifestyle. I recalled a line from David and Daniel Hayes in their excellent father and son tale, My Old Man and the Sea: “When the father helps the son, they both laugh. When the son helps the father, they both cry.’’

Epic days of trade-wind sailing passed in succession, with a happy crew laughing and joking often. I played the song “Sailing” by Christopher Cross, apologizing to the boys because it is perhaps one of corniest songs ever written. It pretty much defines the genre of yacht rock.

Soon they were singing along, bawling out lyrics like: “Sailing takes me away to where I’ve always heard it could be.”

“All caught up in the reverie, every word is a symphony.”

“Oh, the canvas can do miracles.”

As the moon waned, brilliant stars blazed in the skies free of light pollution, and we watched as constellations wheeled across the sky. One night within a few hundred miles of Honolulu, Tracy looked up to see a series of perhaps 20 small bright lights follow each other up into the sky, pass over our heads, and vanish out into space. He called me on deck to witness it. We suspected that these might be a satellite series launch, and indeed it turned out to be SpaceX’s Starlink satellite launches.

The sight left us somehow conflicted. On one hand, we were impressed by this feat of technology, with its potential to improve our lives and bring us closer together. On the other hand, we felt uneasy, as if our precious night sky had somehow been colonized by a for-profit venture—an attempt to steal our attention away from our natural world of ocean and cloud to focus us on tiny glowing screens. We were using an Iridium Go unit to download weather data, a technology that Starlink has supplanted on many yachts. The world at your fingertips, all day and all night. Who has time to look at the stars?

As we approached the Hawaiian Islands, the wind increased a notch, accelerating around our home island chain and its mountain peaks reaching as high as 14,000 feet. Now the trades were over 25 knots, out of the east. It was a dead run, pretty much directly astern.

Experimenting with sail combinations one day, I found that with the higher wind strength, we were able to run straight downwind at close to hull speed under the 120 percent genoa, which surprisingly stayed full dead downwind. This saved us a lot of distance sailed compared with jibing back and forth at angles to the wind. Lacking the stabilizing force the sails would exert on a reach, the boat rolled considerably in the steep seas, but after nearly two weeks at sea, we just rolled with it.

On our 14th day at sea, we sighted the long slopes of Maui’s volcanic crater, Haleakala (house of the sun). Soon after, the highest sea cliffs in the world, on Molokai’s north shore, rose 4,000 feet into the clouds. These looming cliffs guard Kalaupapa, with its mournful history as a leper colony.

We closed with the coast, surfing at 8 knots. Steep breaking seas surrounded Father Damien’s church. (Damien was recently canonized St. Damien for his great sacrifice here.) The area is now a national park. We weren’t permitted to go ashore, but we didn’t mind. We toasted our safe voyage, complete but for the daysail across the channel to Waikiki.

We toasted not having to stand watch. I felt like Bernard Moitessier, the French sailor who continued on around the world again, reluctant to finish the voyage and face the rush of humanity. We had made a fast passage and were ahead of schedule. There was no rush to sail home to Oahu.

With the boat owner’s blessing, we spent a day anchored under the cliffs at Kalaupapa. We were in fact the only boat anchored off the entire north coast of Molokai.

The next morning, I nearly dropped my coffee when a dolphin leaped into the sky a few meters astern of the rail where I stood. It turned out that the boat was surrounded by an inquisitive pod of spinner dolphins, which spent the day circling the clear sandy-bottom bay. Each of us swam out alone several times to commune with them. Curious when we dived down to their level, some swam along with us, seemingly bemused by the awkward humans.

Every voyage should be celebrated, and that single day was distinctive as an epic bookend to a remarkable journey. What made the trip stand out as one of my best-ever voyages was not that we didn’t have problems. We’d certainly had our share, starting with my own bad judgment in the dinghy, but our crew dealt with the problems together, and we shared the experience. And that can only be described as a gift.