A couple of summers ago, I took a Sabre 30 from New Jersey to Maine. The first half of the voyage from Atlantic Highlands through New York City to the Cape Cod Canal required intricate timing of wind and current in constricted waters with long distances between harbors. We had cell service the entire way, so we could pull up tidal information online, but it was always point-based. What I needed for planning was information on how the tidal currents changed throughout a day and over a geographic range.

Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book, aka the Little Yellow Book, was my solution. And I’m far from the only boater who sings this book’s praises. This year, Eldridge is publishing its 150th edition—an impressive feat of continuity dating back to 1875. That’s even longer than the federal government’s stand-alone tide and current tables, which started with the year 1867 and ended their physical printings when the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration took them online-only in 2020.

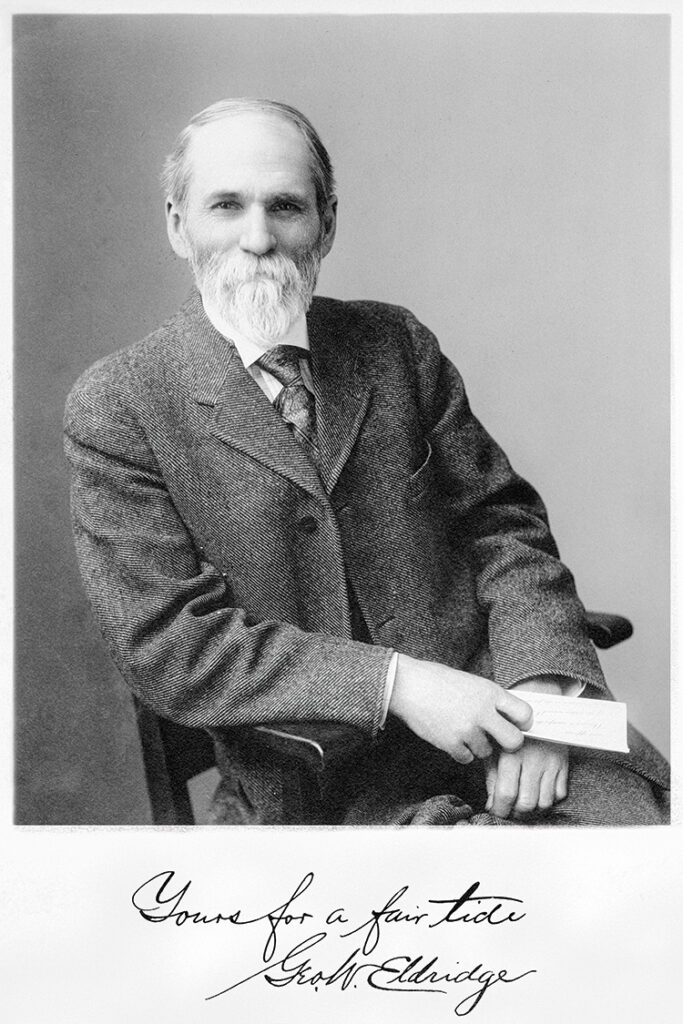

Today, Eldridge covers the East Coast from Canada to Key West, Florida. But the book got its start in Massachusetts, where George Eldridge, a cartographer living on Cape Cod, published his Pilot for Vineyard Sound and Monomoy Shoals in 1854. He sent his son, also named George, to Vineyard Haven to sell the book, which was a combination of sailing directions and nautical dangers. Their target audience was the crew from schooners waiting for a favorable tide to depart. Those boats had to dodge shifting sands and hidden rocks because the Cape Cod Canal didn’t yet exist.

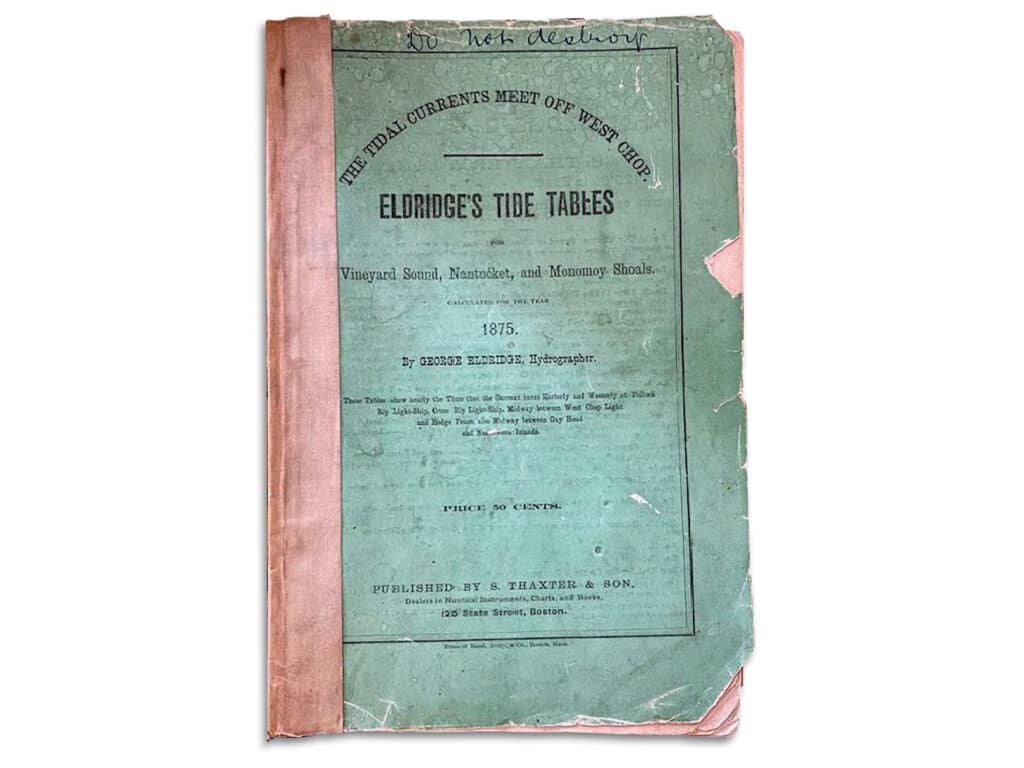

By 1875, the idea for the book had grown into the first edition of Eldridge as we know it today. It was 64 pages long and cost 50 cents. Over the years, new information was added, such as an explanation of unusual currents in the “graveyard” in Vineyard Sound. Many stores began to sell the book around the region.

Today, Eldridge is printed in Indiana after being created at the home of Jenny and Peter Kuliesis in Arlington, Massachusetts. Jenny is the sixth generation of descendants to keep the title going.

“Much of what has helped the book stay in the family is that it has been thought of and treated as a family member,” she says. Parents managed the editing and publishing, and they talked about it over dinner. Children were brought to marinas and boat shows. “As a child, I marinated in the family pride, as I imagine each generation must have before me. It was both a duty and an honor to keep the legacy going.”

I’m particularly fond of Eldridge current charts. Instead of just tables, or even current diagrams, they distill the information into arrows and numbers that show direction and speed on 12 charts, one for each hour of the tide cycle. Using the charts along with tide tables, I can quickly see how a day’s planned trip fits in.

For instance, the trickiest part of my voyage from New Jersey to Maine was timing our entrance into New York’s East River. If the current is right, a small boat will fly along to Hell Gate like a rubber duckie. To achieve this, we had to arrive at The Battery, at the bottom of Manhattan, two hours past low tide.

A look at Eldridge revealed a big problem: It’s 18 nautical miles to get from Atlantic Highlands to The Battery, and almost the entire time we’d be headed north, the tide would be ebbing quite briskly out of New York Harbor. We had to consider not only our average boatspeed, but also the velocity of the current streaming south at more than 2 knots.

Much of what has helped the book stay in the family is that it has been thought of and treated as a family member.

Eldridge’s 12 current charts worked well for us. Eldridge also provides the convenience of having charts and data together because storage is limited on most boats.

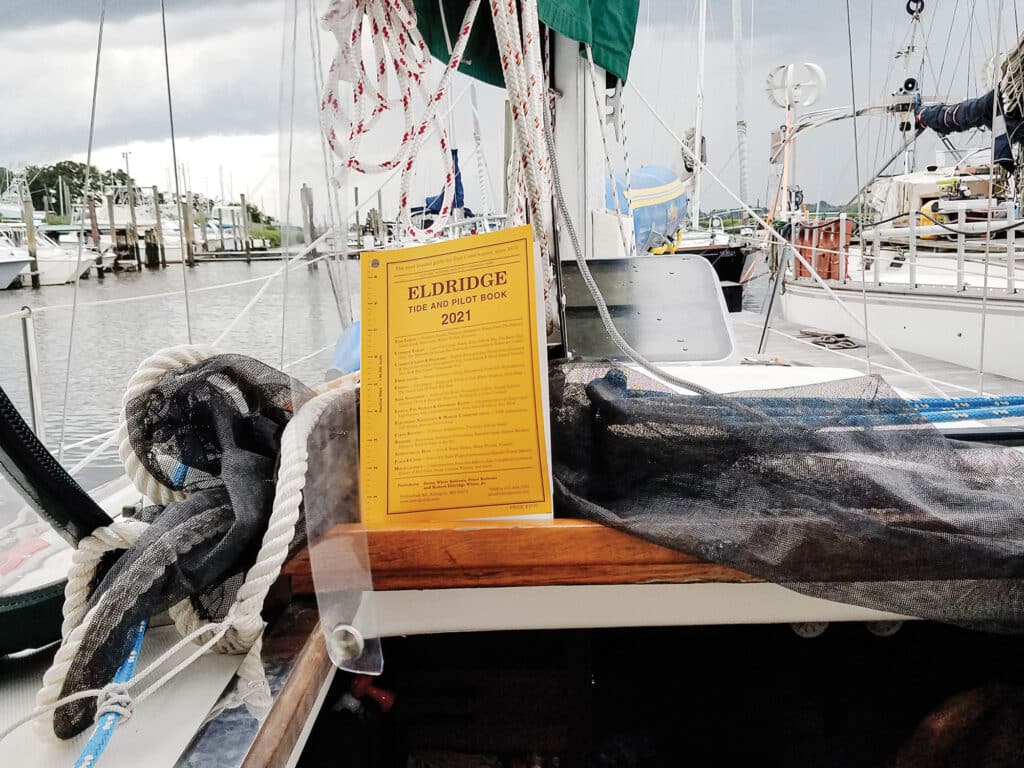

“One aspect of Eldridge that we feel surpasses apps is the ability to easily plan for future trips, as most apps focus on the present,” Jenny says. “We have seen no difference in sales of Eldridge since NOAA’s switch to online tide and currents. Our readers have made it clear to us they value the book in its physical form.”

George Eldridge’s first chart was inspired by a storm that tossed up a new shoal off Chatham, Cape Cod, right across the path that vessels used to pass along the coast. That chart is oddly reminiscent of “mud maps” that my husband and I used in the Kimberley region of northwest Australia: hand-drawn diagrams with all kinds of information that boaters shared.

Since GPS has now been invented, Eldridge still publishes distances between ports, but it no longer gives compass directions. That space in today’s book goes to information about weather, boating safety, first aid, fishing, celestial data, and expert articles chosen by the generations who continue to evolve the content.

“A critical and frequently missed part of our story is how in-laws and the women in the family have contributed, sometimes acting as the primary publisher and not always getting the attention for doing so,” Jenny says.

Jenny watched her grandmother, Molly White, do the lion’s share of the work while her grandfather ran his nautical instruments business.

“My mother, Linda, apprenticed for decades with my grandmother before taking over as publisher along with my father, Ridge,” Jenny says. “My parents were the first generation to shift the role from a family duty to a choice. They had discussions with my sister and me periodically throughout our lives about the true work of publishing the book, and wanted us to go into it with eyes wide open. My parents were slightly surprised, quite excited and, I think it’s fair to say, relieved when Peter and I expressed interest.”

After Linda died in 2015, Jenny and Peter joined Ridge as publishers. Peter has helped by writing programs and formatting data in new and efficient ways.

Are they sailors? Of course. “I grew up messing about in boats, and Peter picked it up when he met me,” Jenny says. “The modest craft in our fleet are greatly affected by tides and currents, and we do much of our boating on a tidal lake with a narrow channel out to the sound.”

They use Eldridge every time they go out and, more often than not, before going out, to plan their voyages. “We have a copy on our sailboat and motorboat, and one at home, so we always have an Eldridge within arm’s reach,” she says.

Today, Jenny and Peter are looking to the future of the book, which some boaters call “The Sailor’s Bible.”

“Our readers let us know that they wouldn’t leave land without it,” Jenny says. “We feel that we must be doing something right, as I can’t think of many other publications that have made it to 150. At the end of the day, if your GPS is on the fritz or your smartphone gets dunked in the drink, you can still navigate safely home with Eldridge in hand.”