Ulysses wasn’t the only sailor to hold a tiller in one hand and take literary notes with the other. Herman Melville wrote about man against sea. Ditto Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad and John Masefield. Popeye. Even Sinbad himself.

There’s something about chasing the horizon that begs to be distilled onto the printed page. Joshua Slocum was a skillful wordsmith. Capt. John Voss and his Venturesome Voyages. Harry Pidgeon. Frederick A. Fenger, my favorite salt-stained ink slinger. Carleton Mitchell. Bernard Moitessier. The lyrical William Albert Robinson of Svaap and Varuna.

And I haven’t even mentioned Jimmy Buffett.

Here’s the truth of it: The fine art of storytelling remains constant and difficult. The only thing better than a sailor is a sailor who can turn a phrase, spin a sea yarn or tell a joke that makes a cabin full of toothless sea gypsies guffaw their rum drinks onto the teak-and-holly sole.

During a long night watch steering my 22-foot double-ender sailboat, Corina, I told my lubberly crew listening belowdecks fanciful tales of shipwrecks, sea monsters and the Mary Celeste. I told these yarns so vividly that the fearful off watch refused to come on deck at eight bells. (I judiciously held my tongue after that.)

Words, water and salt mix with only the slightest of stirs. There’s something about staring God in the eye at the height of a full gale that makes those of us with literary pretensions want to—need to—write it down. The exhilaration of a 30-foot sea sweeping harmlessly beneath our vessel in the Indian Ocean. The glory of the relative calm of its trough, and then the sudden elevator-rise upward. The sound of a million drowned sailors moaning mournfully through your quivering, rail-down rig yet again. And again. And again.

Here is the immensity of raw, primal power. Mother Ocean’s absolute indifference. And death so coy and close that you can smell its breath. Can any man ever feel smaller? Less significant? Less worthy?

My father was a proud man of many accomplishments ashore and afloat, but the thing he was most proud of was being published in Yachting magazine shortly after World War II. We used to chuckle over Martin Luray’s tales in Rudder.

Motorboating & Sailing used to publish the hysterical Dick Bradley and the irreverent Uffa Fox, two of our favorite salt-stained gossips. We’d laugh aloud at the Cap’n Percy Seine column in National Fisherman. Or Fritz Seyfarth’s piratical tales in Caribbean Boating.

Humor always sells for two reasons: Dumb people like to laugh at others, and smart people enjoy laughing at themselves. Did I follow sports? No. Did I follow wacky marine columnists trying to escape to sea between bouts of jail, rehab and alimony? You betcha.

At 5 years of age, I had an extensive pen collection stashed in the fo’c’sle. At 7, I began to carry a dog-eared journal. By 10, I’d underlined (in crayon) all the dirty parts of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. Yes, back in the day, words on paper mattered and thrilled—especially for a wide-eyed liveaboard kid without the distraction of an idiot box (that’s what we called televisions).

Of course, growing up aboard the 52-foot Alden schooner Elizabeth in the 1950s, I always knew that it was my destiny to circumnavigate a time or two. But how to afford it? I decided on my profession at an early age. I remember the exact day.

We’d anchored Elizabeth off the beach. My father and I rowed the clinker-built Lil’ Liz ashore to get some bread. While we were at the convenience store, the newspapers arrived. A team of international climbers had made history by climbing a particular lofty peak.

“Wow,” the store clerk said. “To climb one of the tallest, sheerest mountains while it’s covered in snow—that must be the most difficult thing to accomplish in the whole wide world.”

“Actually,” said my father, who was in the middle of writing one of his articles, “writing a simple declarative sentence is the hardest.”

From then on, despite not being sure what a simple declarative sentence was, I knew what I wanted to dedicate my professional life to.

A few years later, I returned from a day at elementary school to Elizabeth. We were docked in slip No. 7 at the basin. As I approached, I heard crying. I crept aboard and peered down through the open skylight. My mother had tossed all 400 pages of the manuscript she was writing onto the cabin sole. She was sitting and crying amid the chaos of her literary dreams.

Mom wasn’t a quitter—she was finally published at age 86—and I embraced the lifetime of suffering earlier than she had. I didn’t permit the fact that I had failed sophomore high school English to discourage me.

Figuring out a way to make money regularly dribble out of a pen isn’t easy. The competition is extreme. The pay is minuscule. I knowingly and willingly aspired to a profession that was crap—but that included a cruising lifestyle that was priceless.

The first thing I did was to spend an entire year—365 days, 24/7—solely focused on learning how to write. My mission was to get anything published by any publication for any amount of money within the year.

Six months in, I made a new goal: to collect 100 rejection slips from national publications. Hell, I’d proved I was good at that.

My wife called my stories homing pigeons because, no matter where I sent them, they came right back. A number of editors, tired of turning down my stories, asked variations on, “Mr. Goodlander, do you realize that trees had to die so you could write this?”

I wrote a dozen finely crafted tales that I thought would be ideal for Caribbean Boating and brought them to founder and editor Jim Long.

“Forty bucks,” he said after glancing at one.

Now, some of those precious stories had taken me months to write, but my pregnant wife was starving—and $40 times 12 stories is almost $500.

“OK,” I said, swallowing my pride.

It wasn’t until months later that I realized Jim had meant $40 for all of them. And he didn’t pay me actual cash; he gave me the name of a deadbeat convenience shop that had advertised with Caribbean Boating, and told me to pistol-whip the cash out of the recalcitrant fellow behind the counter. The quaking grocer really didn’t have any money at the time, so I was forced to shoplift an armful of Planters Peanuts to collect my pay.

Six months in, I made a new goal: to collect 100 rejection slips from national publications. Hell, I’d proved I was good at that.

The next time I asked for payment, I had to wrestle it out of a fish wholesaler at Red Hook on St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. My still-pregnant wife complained: “I thought getting paid in peanuts was bad. Dead fish is even worse.”

Since scraping the bottom of the literary barrel hadn’t panned out, I decided to reach for the sky. My hero, Martin Luray, had left Rudder as it sank in heavy financial seas. I submitted stories to his new home at SAIL magazine, with my over-the-transom submissions flagged to his attention. He promptly started buying them. At the time, I considered $250 apiece all the money in the world.

After he published my third story, “The Last Cruise,” he excitedly called me to announce that it had “received more positive mail than any story we’ve previously published. You’re on your way, Fatty.” I promptly demanded double the money per story—and immediately got it.

Thus, I learned an important lesson: It isn’t the editor, but instead the readers who sign a determined writer’s paycheck.

There was a problem, however. Rightly or wrongly, I always considered SAIL readers above my financial station in life—and the steel-and-chrome publication seemed to agree. They refused to accept my byline of Cap’n Fatty and forced me to write as Gary M. Goodlander—a name I’d only heard from angry cops, disgusted judges and near-suicidal teachers. Hell, if my wife, child and mother called me Cap’n Fatty, why shouldn’t my readers?

This requirement grated. And, worse, I had always believed that Cruising World, not SAIL, spoke to my natural pool of readers—the real, actual cruising community, not the blue-blooded, well-heeled racers of New England. I didn’t want to wear a blazer and sip chardonnay at trophy-filled yacht clubs. I wanted to tie one on with the rowdy shipyard workers along the waterfront.

Wish in one hand and spit in the other to see which fills the fastest. Cruising World already had a funny marine columnist named Tom Neale, whom I much admired. Thus, I felt awful (not awful enough not to, but just awful enough to wallow in self-pity) writing whiny missives to editor Elaine Lembo at Cruising World, telling her that I was born to write the magazine’s On Watch column.

“You’re too earthy,” she wrote back, proving she was a good judge of character.

Now, I might not be bright or particularly talented, but I’m stubborn and goal-oriented. I’m stupidly tenacious. There was only one other marine publication besides SAIL and Cruising World that paid enough to keep my wife and me in bilge scrapings: Yachting World.

Once, during Antigua Sailing Week, my drinking buddy was a likable lush named Dick Johnson. I gave him a vomit-specked copy (too earthy) of my book Chasing the Horizon for his plane ride back home to England. He read it while sitting in first class—and was surprised when an angry passenger loomed over him and hissed, “Hey, pal, either stop laughingor read it out loud.”

Dick had been too smashed while racing to reveal that he was editor of Yachting World. Or I’d been too drunk to remember if he did. But it came as a shock when he offered me exactly what I’d always wanted: a regular column at a respected marine publication with deep pockets.

My wife, Carolyn, and I popped a bottle of cheap champagne. But alas, before Dick and I could hammer out the contractual details, Yachting World was sold to a new owner, Dick was fired, and the newly installed secretary refused my (collect) transatlantic calls.

Now, I’ve screwed up many an important assignment, but this was the first job that I’d been fired from before I even started.

In the mid to late ’90s, I sold my first story to Cruising World. I was in shock to be writing for the same publication where I’d read Eric Hiscock, Bernard Moitessier, Robin Knox-Johnston, Carleton Mitchell, Irving Johnson and a dozen other of my literary heroes.

It didn’t seem real. I felt like an imposter—a very happy, grateful imposter.

Enter fellow Chicagoan Herb McCormick, who took the reins of Cruising World about 25 years ago. Despite moonlighting for the staid New York Times, Herb wanted to shake things up at Cruising World—and tossing me into the editorial mix was nuclear. He dangled the cherished plum in front of me: the monthly On Watch column. And being listed on the masthead as editor-at-large. (I had no idea what that meant—still don’t.)

Oh, and Herb generously tossed in some freedom chips as well. No more pistol-whipping deadbeat grocers. No more dead fish.

If not for Herb, I would not have achieved by life’s dream. I’m appreciative. And grateful. And will steadfastly remain so—which isn’t to say that our relationship was entirely seamless. However, to his credit, he always rehired me within 48 hours of firing me.

John Burnham was my next editor. I grew to have immense respect for him as a man, editor and sailor. I also worked closely with Tim Murphy, who was tough but held the fragile concept of storytelling in mystical regard. I learned a lot from Tim. (He’s a wooden-boat freak and guitarist as well. No wonder we get along.)

Next up was Mark Pillsbury—perhaps the finest line editor I’ve ever worked with. And today, as the publication approaches its 50th anniversary, its current masthead brings a renewed energy and commitment to set Cruising World on a fresh tack that will see it into the next 50 years.

Of course, some change is inevitable. Once upon a time, the only way for, say, farmers in Omaha, Nebraska, to meet people like me was through publications such as this. Now, the growing roar of online video is drowning out the whispering of my arthritic fingers on my decrepit keyboard. So be it.

What my pen has learned in its 25-year association with Cruising World is that the readers steer an enduring publication, not the staff or advertisers. You speak; we listen. It is we who labor in the literary vineyards in service to you.

If I’ve ever made any of you laugh during the past two decades, I’m humbled and proud. But, more important, perhaps I’ve made a Cruising World reader think, If Fatty can circumnavigate, so can I.

Mission accomplished.

Birth of a Brand

Fifty years ago, when the sailing world was largely preoccupied with the thrill of racing, a quiet revolution was brewing.

The early 1970s painted a much different picture of cruising than today. While the Caribbean and Bahamas were established cruising grounds, the lifestyle was still seen as a daring escape, a romantic pursuit for the adventurous. The Mediterranean was not as accessible as it is today. It was just beginning to attract cruisers with its rich history, beautiful coastlines and charming ports.

Sailboats—the backbone of the cruising fleet—ranged from small, nimble vessels for couples to larger family cruisers. Most boats were still built using traditional materials such as wood and fiberglass, with early experiments in aluminum and steel. Cruisers were self-sufficient pioneers, relying on their own skills and ingenuity to navigate the challenges of life at sea.

Enter Australian visionary Murray Davis. As history tells it, Davis and his wife, Barbara, bought a 39-foot sailboat in Copenhagen in the late ’50s. They lived on it through a winter in Paris, and with the spring, traveled south to the Med. Barbara’s sister and her husband, George, a master mariner, joined the Davises for their first real cruising lessons. After two weeks of sailing the Spanish coast, Murray asked George, “Do you think we know enough to make the trip to Australia?”

“Go,” he replied. “One never knows enough.”

The couple did so, and sailed as far as the West Indies.

Years and thousands of nautical miles later, Murray, then based in Newport, Rhode Island, saw the cruising community as a vast, untapped audience—individuals driven by a yearning for adventure, independence and the open sea. Boating magazines existed, but none catered exclusively to the needs and aspirations of cruisers. Murray envisioned a publication that would become a go-to resource for cruisers, providing practical advice, inspiring stories and a sense of community.

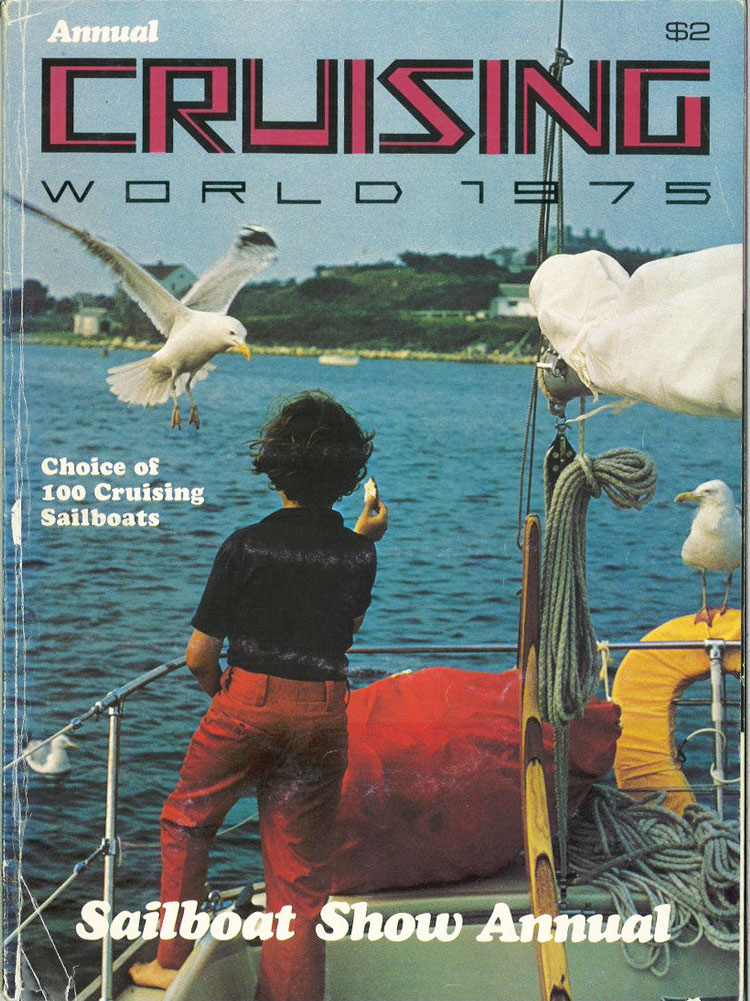

In 1974, Murray and Barbara launched Cruising World on a tiny budget and a whole lot of hope.

Cruising World immediately resonated with sailors worldwide. Its ever-growing list of writers included real cruisers explaining things such as how twin headsails worked, or marveling at the breakthrough of Blondie Hasler’s windvane self-steering device, or scrutinizing electronics for the small-boat sailor. It featured luminaries the likes of Eric and Susan Hiscock, Claud Worth, and Erroll Bruce. Others would follow, including Jerry Cartwright, Katy Burke, Bruce Bingham, Sven Lundin, Lin and Larry Pardey, Jimmy Cornell, and so many more. They all wrote and talked about the stuff that people caught by the romance of small-boat sailing wanted to know.

The first issues of the magazine clearly laid out its mission, with stories from many parts of the world, told for sailors by sailors. Titles set the early tone: “Shortening Sail,” “Tenders,” “Hidden Costs of Cruising,” “How To Enjoy Wet Weather” and “From Here to There With Nothing but the Wind.”

Throughout the decades, Cruising World has evolved, but it has always stayed true to its commitment to provide sailors with the information and inspiration they need to fulfill their cruising dreams.

“You can never know enough,” Murray once said. “But to try is, for many, to live.”

—Cruising World Staff