In late 1984, with 2,000 miles of California sea trials and easy Baja California cruising behind her, Taleisin could no longer be called a new boat. We’d tested her power as we beat north against 25-knot winds to revisit the magic hideaways of Mexico’s Gulf of California. As we explored the hidden coves we’d prowled around 16 years before on Seraffyn in the tranquil waters of the Bay of La Paz, we’d found the best leads for our light-air sails. A few fresh reaches had forced me to rearrange lockers so I could actually get at the provisions I wanted even when I wasn’t feeling my very best.

Now, as we left Cabo San Lucas, bound for the Marquesas, Taleisin was in top sailing shape, though she was loaded well beyond her designed 17,400-pound sailing displacement. In fact, a check of her waterline marks showed her ready-to-depart weight was close to 18,600 pounds. But other than four baskets of fresh, fragrant fruit and vegetables, which we’d wedged securely at the head of the forward bunk, everything was hidden in its proper locker.

Ahead of us now lay a whole new world. In 18 years of voyaging we’d never once poked our bowsprit south of the equator, never visited a South Seas island or coral atoll, never heard the throbbing drums of Polynesia.

Two days’ sailing south of Cabo San Lucas lay Socorro Island. Rugged and desolate, it is inhabited on shore only by a small contingent of Mexican soldiers. Underwater it is reputed to be haven to the largest spiny lobster population in the Pacific. We planned to stop for a few days and enjoy a few good meals before setting off for the long haul to Polynesia. It was late morning when we reached in toward Socorro’s only tenable anchorage, an open bay tucked tightly against the southwest corner of the island. The water within the bay didn’t look right. I got out the binoculars and could make out wispy plumes of spray, then the slowly arching backs of seven gray whales as they stirred the waters by moving in a slow pavane, circling the only shoal area we could safely employ. We dropped the small genoa and, under staysail and main, reached closer. Larry tried to reassure me: “They’ll leave any second now. Besides, they’re probably farther offshore than they look from this angle. We’ll sail in past them and have lots of room to anchor.”

He was wrong on all counts. The placid behemoths ignored us completely as we slowly reached alongside them. They carried on with their mating activities. I threw the lead line to sound the anchorage; they still didn’t leave. In fact, the closer we got, the more they seemed to fill every bit of space, swimming to within a dozen yards of the shore with their massive, heaving, barge-like bodies.

We jibed, then reached clear of the anchorage, and as the full swell of the open ocean again caught us I said, “Let’s forget Socorro — wind’s fair, let’s keep going.”

But Larry’s eyes had their mad hunter look. “Remember what that Mexican diver told us about the lobster here. Probably never have another meal as good as the one we’ll have tonight.”

So we winched home the sheets, tacked over and left the staysail backed. Taleisin slowly lost way and lay comfortably hove-to while I made lunch. Two hours later we eased the staysail sheet to turn and reach back in to the anchorage. By then, our harbor mates had moved … somewhat. Now there was almost enough room for us to set our anchor as the whales nuzzled around each other, completely ignoring us. But not quite enough. So we jibed and reached out into the open water again, to lay hove-to for another hour. Then we sailed in yet again. The necking-party-cum-gossip-session seemed less intimate now as the whales swam in three separate groups. Amid them there appeared to be just enough swinging room to set our anchor. Before I could change my mind, Larry had unclutched the anchor windlass and eased out our 35-pound CQR with 150 feet of chain.

Our big gray cove mates ignored the rattling chain but acquiesced to our territorial claim, swimming and cavorting just clear of Taleisin. I turned to Larry.

“Going in for some fresh dinner fixings? I’ll get out your fins.”

My urgings, definitely made in jest, were ignored. He sat next to me on the cabin top, imagining the teeming sea life crawling through the crevices and crannies of the sea-washed rocks just 200 yards from where we lay at anchor. That evening, as we chewed our way through some durable Mexican chicken and braced ourselves against the slight surge in the anchorage, the whale-induced wavelets and occasional gusts of the fresh westerly breezes scooting down from the hills inshore of us, Larry said, “I’ll slip overboard and chase up a bug or two tomorrow, when our friends move on.”

But by morning it was we who decided to move on — to get a good night’s rest by going to sea. The serenade of whale spouting, augmented by what we took to be sighs of sexual delight, had kept us both on the edge of wakefulness through the night. Within an hour we were free of the wind shadow of Socorro Island and gliding over a sun-speckled sea, three sails set to catch the 15-knot westerly.

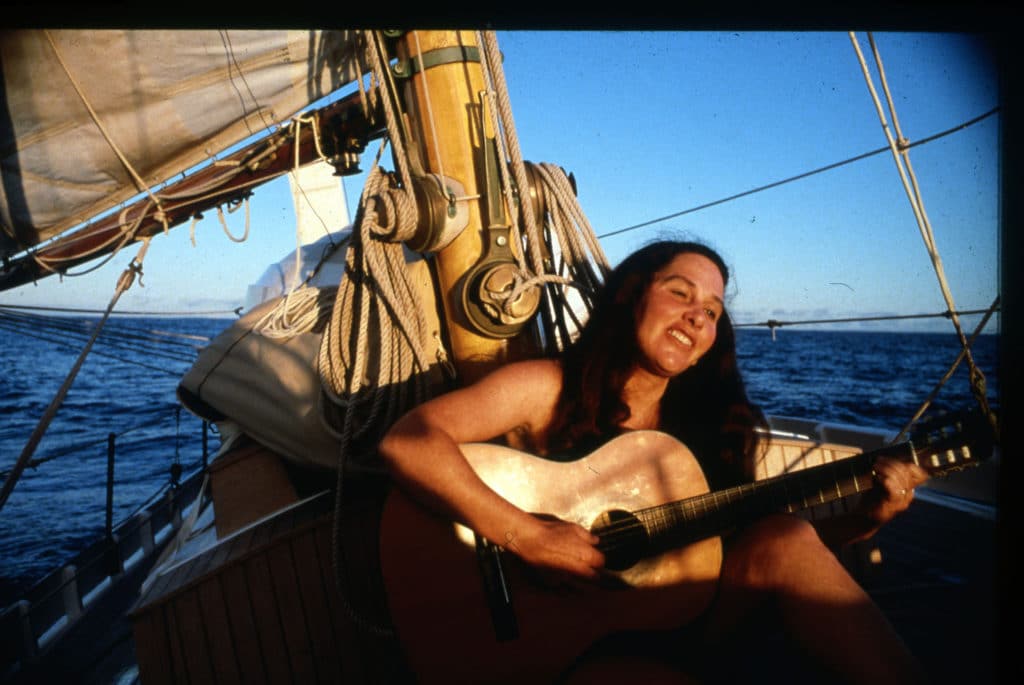

The wind slowly eased aft from our beam to cross our stern until we were running wing and wing in the northeasterly trades. The only comments worth recording in our log, other than course and distance made good, were: “baked bread, had a hot shower, took cushions out onto the foredeck for the afternoon, made love in the shade of the drifter.”

As I read that comment now, decades later, the scene floods back in warm details: the green-and-blue striped sail arching over us, providing a perfect screen from the tropical sun; the smell of fresh bread slowly baking belowdecks; the sound of Earl Klugh’s guitar carrying softly from our stereo, his strumming almost in perfect rhythm with the hiss, then gurgle, as Taleisin’s bow rode over the crest of each surging wave.

For once I truly believed perfect trade-wind sailing existed. We’d found it, and Taleisin loved it. The string of noon-to-noon runs recorded in our log belied her relatively small size: 158, 165, 176, with the current giving us a few extra miles on top of that. The days sped past in the easygoing, intimate routine that seems to develop on board a two-handed sailboat during an ocean passage.

Keeping the necessary round-the-clock watch means Larry and I spend little time actually being together when we are at sea. Three hours on, three hours off all night, our only communications being a quick update from the person coming off watch. We each then spent two hours napping later on to top up our need for about eight hours’ sleep each day. Then there was the time needed to make occasional sail changes, navigate, clean up inside the boat, check the gear on deck, check the fresh produce for signs of deterioration. With only the two of us on board, we find that at sea we have less than four hours of unstructured time for cooking, eating and communications. If one or the other of us happens to be fully engrossed in reading a book we “just can’t put down,” we find our only true time together happens as we share our evening meal. Then begins the routine of settling the boat for the night and having a quiet drink, a quick sing-along or a shared chapter from a book we might choose to read aloud together before Larry climbs into the bunk.

As on all previous passages, we stuck to our routine of having the same watches each night. Studies by sleep psychologists confirm what we have learned by trial and error. Our body clocks adjust more quickly to sleeping during the same time periods each night instead of dogging or alternating watch hours.

Two things began to indicate the unique nature of this passage. First, not one of our night watches was interrupted by a call for assistance. The second oddity: By our 10th day out from Socorro we hadn’t found the doldrums that should have slowed our progress well before we reached the equator. In fact, when our sights showed a current against us — a sure sign of the edge of the doldrums — the seas steadied and the wind shifted just enough to put us on our fastest point of sail, a beam reach. Taleisin, with her modest 27-foot-6-inch waterline, turned in a wondrous series of noon-to-noon nautical-mile runs: 168, 176, 171. Our taffrail log reading and celestial sights concurred to within a mile or two to rule out help from stray currents.

As exciting as this was, it presented a new problem.

Both of us are fair-skinned. Many years of enjoying sailing before medical science made the link between sun exposure and skin cancers meant we’d both acquired a fair sprinkling of keratosis (the early stages of skin cancer). These scaly patches and recurring small lesions had, in the past, been frozen off during a visit to the doctor’s office. Recently our personal physician had suggested an alternative — a chemical treatment called Efudex, which we’d tried under his direction (made by Roche Ltd., it’s basically chemotherapy for the skin, using fluorouracil cream). We’d apply the stuff twice daily for three weeks; the sun spots would redden, turn to open sores and then scab over and heal, leaving behind blemish-free skin. The spots we’d treated under the doctor’s supervision had all been on our forearms and easily hidden from public view. Now the affected areas were on our faces. We kept putting off the treatment, waiting for a time when we’d be away from people for a while. The time seemed right on this longer passage.

“It’s more than 2,500 miles to the Marquesas,” I’d said to Larry when we left Mexico. “We’ll be at sea for three weeks or more. If we start the treatment a day or two before we leave, our skin will be all cleared up before we get there.” But by our 13th day at sea, when another 158-mile noon-to-noon run put us within 400 miles of Nuku Hiva, I looked at Larry’s splotched countenance, then took a mirror to inspect my own ravaged face, and knew we’d made a slight miscalculation. Both of us looked like refugees from a fire. Unless we hove-to for a few days, we’d arrive appearing almost leprous.

There is a saying among sailors: “Put one sailboat within sight of another and both will start racing.” There wasn’t another boat within hundreds of miles of us. But the splendid record of miles made good was as much of a prod as the sight of another sail on the horizon. So, in spite of our appearances, we kept Taleisin running as fast as she could, the drifter set to one side on the 20-foot spinnaker pole, the mainsail to the other.

On the morning of the 16th day at sea, the craggy outline of our first South Seas island seemed to burst over the horizon. Taleisin surged down the trade-wind swells as the sheer black cliffs of Nuku Hiva slid ever closer. The fish line we’d been trailing for almost 2,400 miles sprang to life, sounding the alarm Larry had jury-rigged by putting a couple of nuts and bolts inside an empty beer can.

Larry almost trampled me as he rushed through the cockpit to grab the line. A gold-fringed tuna leapt into the air, growing ever more frantic as Larry pulled it hand-over-hand toward the boat, then flipped it over the lifelines. I ran as far out of the way of that flailing flash of silver as I could, clinging to the fish-free safety of the boom gallows until it was subdued. My screams of “Kill it before it jumps down the hatch!” died in my throat as a strange black smoothness disturbed the crest of the swell ahead of Taleisin. The next 10-foot swell lifted Taleisin’s stern and sent her scudding downhill amid a burst of foam, guided only by the wind-vane self-steering gear. She seemed to hang motionless for just a few seconds in the trough of the sea as I pointed in stunned silence. Less than 10 feet away on our beam, two huge whales lay side by side, gently spouting, basking serenely, unaware that only fate had kept 9 tons of rushing timber and lead from landing on their backs.

“Luck, only luck. That’s all that kept us from a real catastrophe,” Larry whispered as he held the slowly dying 8-pound tuna against the leeward bulwark rail with his foot.

My mind was filled with visions of a massive, angry fluke smashing through our teak planking, driven by 20 tons of terrified mammal. From the look in Larry’s eyes I could tell he was recalling another encounter with sleeping whales almost 18 years earlier, when he’d been first mate on an 85-foot schooner called Double Eagle. He’d been at the helm when, halfway between Hawaii and California, they’d sailed quietly past a basking whale. One of the crew tossed an empty beer can at the mammal. Its frenzied dive had sent cascades of salt water right across the massive schooner to drench the crew.

“If that fluke had hit our stem, it would have shattered it,” Larry had often told me.

Now we watched in silence as, astern, white wavelets washed across the backs of the whales. Taleisin lifted and fled before another trade-wind swell, and within two minutes those whales were lost from view. The smells of approaching land slowly invaded my senses. The last death throes from the fish Larry was still holding under his foot brought him out of his shock-induced trance. We were soon occupied with fish filets, sail changes, navigation. Neither of us mentioned our close encounter with those mammoth creatures that shared this water with us until we lay in our bunk together late that evening.

It was dark when we short-tacked between the towering sides of the Marquesas’ Taiohae Bay and shattered the quiet with the rattle of our anchor chain. Sixteen days, six hours out of Socorro we lay at anchor after a passage that could be described as close to perfection.

Morning brought reality with it.

At the first sight of our yellow quarantine flag, the health officer arrived. He took one look at our sore-encrusted faces and informed us we were confined on board until further notice. Our attempts to use our 20-word French vocabulary failed completely. But he did take our tube of Efudex with him and made it clear he would be contacting the authorities in Papeete, Tahiti, for further instructions. It was late afternoon before he returned, accompanied by a customs official, who carried a bottle of wine to officially welcome us and invite us to explore his island home.

An old sailing friend once said, “You’ll go out sailing 10 times, then you’ll hit one day that is sheer magic. You’ll be hooked and go out again and again trying to fall under that intoxicating spell once more.” When I look back at all the voyaging we’ve done, I have to agree with his sentiment: Truly memorable days were vastly outnumbered by those days when the sailing was merely pleasant, or other days that were utterly mundane or even downright difficult. I knew this would be the case as we voyaged onward on Taleisin. But now, the difficult and stormy days, as well as the mundane ones, are set against the memory of our highly satisfying dash, neatly sandwiched between two whale tales, from Mexico to the South Pacific.

Long acknowledged as the “first couple of cruising,” Lin and Larry Pardey are two-time circumnavigators aboard boats they built themselves and the authors of 11 previous books. This story is excerpted from their 12th and latest, Taleisin’s Tales: Sailing Towards the Southern Cross (L&L Pardey Publications, 2017).