We had it all planned out so our crossing of the Indian Ocean would be another South Pacific-like voyage. Yes, the passages would be longer and the islands fewer, but we’d still have a smooth run. We’d stay north enough to escape the cross seas of the Southern Ocean and south enough to escape the Asian monsoons. Our itinerary would be Darwin, Australia, to the Cocos Islands, Chagos, the Seychelles, Madagascar and then South Africa. By the time we reached Darwin, however, this was impossible. Somali pirates had captured a motoryacht and a tourist boat right on that route, in the Aldabra group of the Seychelles.

That was a shock. Of course, piracy reports are always alarming, but both these hijackings were well outside the Somali pirates’ supposed range. Until then, they had riled up a 600-mile sweep from their bases, concentrated around the route to the Red Sea and Suez Canal. Now they had extended that to the entire northwestern Indian Ocean.

So our new plan headed us much farther south, from Darwin to the Cocos, the Mascarene Islands and South Africa. Both my husband (then boyfriend), Seth, and I were disappointed to be missing the uninhabited Chagos, for which we’d gone through the expensive process of obtaining a permit. But we both preferred to be cautious rather than end up in the Somali bush. We were kids — I was 23, he 26 — on a half-century-old boat we’d restored ourselves. Ransom wasn’t in the budget. We both wanted to stay well clear of pirates, even if it meant not only missing Chagos, but making longer passages and weathering the reputed high winds and confused seas of the southern Indian Ocean. The 2,000 nautical miles from the Cocos to the Mascarenes is notorious for big cross seas coming up from storms in the Southern Ocean. They meet the trade-wind swell and give a small boat a nauseating corkscrew motion. On top of that, at the time of our crossing, the Indian Ocean Dipole (a weather phenomenon akin to El Niño) would be pushing very strong easterly winds along our route. All of that, though, still seemed better than years spent captive in Somalia.

We’d researched the Cocos Islands and wanted to stay there as long as possible, especially if we were going to miss the colorful reefs and white sand of Chagos and the Seychelles. It was everything we’d hoped for, even if the wind did tear through the coconut palms without a break. We were in a turquoise atoll with some of the most pristine coral I have ever seen, an outpost of tropical beauty in an otherwise deserted ocean. Just as we’d expected, Seth and I found it hard to tear ourselves away. By mid-September, though, we were on our way to the Mascarenes: Rodrigues, Mauritius and Réunion.

A Photo in a Magazine

We knew almost nothing about these islands because we hadn’t originally planned to call at them. We had no guidebooks, no cruising guides — only our paper charts. The islands were simply there, on the general Indian Ocean chart, en route to South Africa and far enough away from the pirates. The only inkling we had of what lay in store was a picture I’d cut out of a Qantas in-flight magazine left in the boatyard bathroom in Darwin. It was of Piton Cabris, on the French island of Réunion: a lush mountain rising out of a riverbed, framed by the equally lush walls of a caldera. I’d found it at about the same time we’d decided to give up our cherished Chagos and Seychelles plan. It had picked me up. Réunion, or at least that valley, must be stunning.

The picture had kept me going through six weeks of major hull repair in Darwin — six weeks of sweltering in Tyvek suits and respirators while Seth and I cured Heretic, our 38-foot cutter, of osmosis. Then I’d forgotten about it in the Cocos. Now, crossing the southern Indian Ocean, I needed it again.

Throughout the passage, the southeast trade wind never dipped below 25 knots and more often blew 30. Rainsqualls with winds up to 40 knots seemed a daily occurrence. Waves slopped over the windward quarter to fill up our cockpit again and again. Our foul-weather gear started to grow mold. Being an old and heavy cutter, Heretic didn’t help the wetness. Displacing 24,000 pounds, she doesn’t rise to the swell like a modern boat, so the latest wave was constantly sloshing around our knees. But Heretic stood up to it, and even with her 27 feet of waterline, she covered the 2,000 miles in only 15 days. We were proud of her. It was our fastest passage yet.

Other landfalls may have been more spectacular — the vertiginous Marquesas, the glaciated peaks of the Alaska Peninsula — but not many have been more welcome than the low, brown hump of Rodrigues. Dry land! “Dry” being the operative word. Beyond that first glimpse, though, Rodrigues didn’t look like much. It certainly didn’t have the grandeur of that picture of Réunion.

Seth and I steered Heretic into the tiny harbor, cut out of the coral, around 1900. It was two hours after the customs office had closed, so we expected to clear into the country in the morning. But no — there were three officials standing on the wharf, ready to take our lines and go through the formalities, at no charge. The formalities weren’t very formal, either. The officials had come down from their after-work beer to meet us, and within 15 minutes we were all fast friends.

“Rodrigues will be your favorite place,” said the immigration officer, and Seth and I nodded politely. Little did we know that all three Mascarenes would indeed be some of our best ports of call during our entire circumnavigation.

Rodrigues is a semiautonomous territory of neighboring Mauritius, and Heretic was tied to the main wharf in the capital city, Port Mathurin, which boasts a population of 6,000. There was no barrier between the port area and the town, and yet we always left our hatches wide-open, such was the character of the place. Heretic was the only foreign boat in the harbor, and news of us spread quickly. A restaurant owner who collects photographs of visiting yachts paid us a visit, and we were soon friends with him and his sister, spending most of our evenings together. The woman in the pastry shop knew who we were before we’d even been there. And all the way across the island, the guide at the tortoise conservation center greeted us with “You’re the people from the sailboat.”

Seth and I had taken public transit — rickety and fancifully painted school buses — to the tortoise center after learning about it from the immigration officer. The center breeds both vulnerable Aldabra and critically endangered Madagascar (Ploughshare) tortoises, and it’s Rodrigues’ only real tourist attraction, though all the “tourists” are Mauritians. All three Mascarene islands formerly had their own populations of endemic tortoises and birds, which, with a few exceptions, were hunted to extinction with the arrival of the first humans in the 16th century. The most famous of these is the dodo of Mauritius. The tortoise center can’t bring back Rodrigues’ two unique species — the domed and saddle-backed tortoises — but it can keep alive the giant and long-lived Aldabra and the beautiful and highly threatened Ploughshare. The center also protects Rodrigues’ endemic bat population, tries to re-establish native plant species, and incorporates a large limestone cave in which people have taken shelter during cyclones. Already the Mascarenes were showing themselves to be one of the most interesting archipelagos on our voyage.

When I was little, my parents often took me trekking in the western mountains of the U.S., and that cut-out photo of Réunion had rekindled my interest in hiking. So on our first morning in Rodrigues, we hiked through an ebony grove to reach a high point from which we could look down on the capital. We summited the island’s highest peak, all 1,300 feet of it; we tramped through a eucalyptus forest until we’d found one of Rodrigues’ rare remaining endemic birds; and we hiked and picnicked along the windward shore, where whistling pines sang in the trades and felucca-like fishing vessels sailed below us in the shallow lagoon.

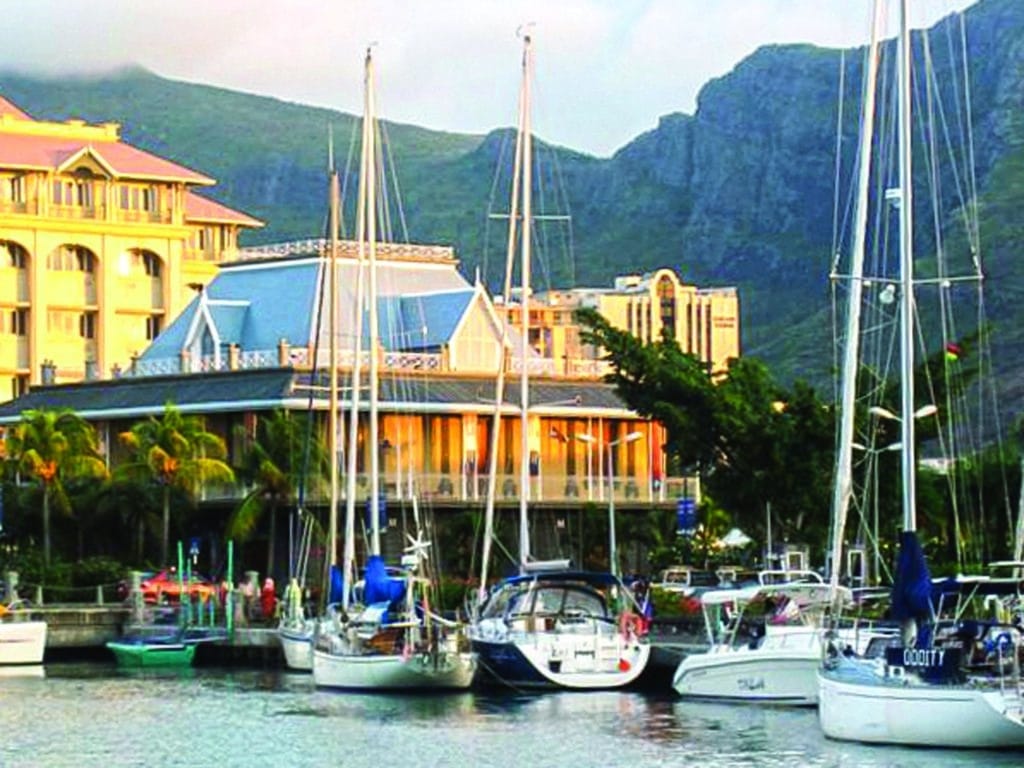

Soon it was time to set sail again, but not too far — just 350 miles to Mauritius. We were excited to see it. Our friends with the restaurant had told us all about the main island of the archipelago, with its vibrant culture, sand beaches and forested mountains. At the end of another bumpy passage, the Indian Ocean put on a terrifying display of lightning, so we were extremely happy to reach the capital of Port Louis safely.

Hints of India

At first Port Louis proved difficult and disappointing. The officials were slow and bureaucratic, and the marina was a concrete pier in an outdoor shopping mall. The city’s population is 25 times that of Port Mathurin, so initially we had a strong dose of culture shock. As we got to know it, however, we discovered the town’s charms. French and English colonial architecture give the streets a historical look, but most of the residents are of Tamil origin and have stamped their culture on the city. The scents of watercress and coriander overwhelmed the immense vegetable market. The streets were crowded with vendors selling everything from red lentils to sequined cloth for saris. Hindu temples brought splashes of color and riotous sculpture to every neighborhood. Movie theaters advertised Bollywood films. A sailor moored next to us, who’d worked in India, asked us if we’d ever been there; when we said no, he replied, “Yes you have!”

Outside the city, acres of sugar cane rippled in the omnipresent wind, and mountains rose as lush and green as in the Marquesas. A national park sits in the most pristine part of these mountains, and Seth and I spent some of our happiest moments on Mauritius wandering its trails, looking down long valleys to the ocean, marveling at the enormous drop of a waterfall, and spotting green parrots camouflaged in the leaves. White sand beaches lined the coast, and although some of them were private, we found a clean and lovely public beach where we could swim in clear water and even scuba dive on a coral reef alive with nudibranchs and lionfish. It turned out there was no need to mourn the loss of Chagos’ reefs.

Often you remember a place best for the people you meet, and on Mauritius that person was Benoît. He was a French machinist in the big shipyard, whom we met quite by accident when a taxi driver interpreted “machine shop” as “commercial shipyard.” The heavy swell of the crossing had worked our bronze steering quadrant so much that its keyway needed to be refashioned — hence our search for a machine shop. When the taxi driver ushered us into Benoît’s cavernous workplace, we decided there was no harm in asking. Benoît dismissed it as a tiny project — he was used to working with commercial freighters — and we started to turn away. “So I’ll do it for free,” he finished. He came to the rescue again when we started up our engine to depart and the exhaust manifold fell off, corroded right through.

Mauritius is also a gathering point for cruisers about to make the crossing to South Africa. Many sailors finish their voyages in Australia or explore Asia instead, so there aren’t too many in Mauritius, and we got to know most of them. By this time it was fairly late in the season, mid-November, so everyone was eyeing the weather charts.

Mauritius to South Africa is a tough passage due to regular gales meeting the Agulhas Current flowing down the coast at 5 to 6 knots. We all had to find a good weather window to make the crossing, and at one point while Seth and Benoît were still at work on our exhaust manifold, one came. The harbor cleared out.

Seth and I knew we were pushing the cyclone season, but after staring at that picture of Piton Cabris for months, we had to see Réunion. As soon as our exhaust was spurting out of the hull instead of into the bilge, we sailed the 150 miles southwest. The washing-machine seas had died down a little, making this our most comfortable sail since leaving the Cocos. Then we spotted the mountains of Réunion, soaring 11,000 feet out of the sea.

One Particular Peak

Leaving Heretic in the small but well-kept marina of Le Port, we headed for the interior aboard one of the yellow coach buses that are the French island’s public transportation. Fifty percent of the island is a national park, and many well-maintained hiking trails crisscross it.

I didn’t know where exactly Piton Cabris was, but it hardly mattered; the whole island was covered in mountains. Seth and I planned to hike part of the Grande Randonnée 1, a circuit that unites the three calderas surrounding Réunion’s highest peak. It’s impossible to have any idea of the scale of these calderas until you’re in them.

We started in Cirque de Salazie, green and lined with waterfalls, and on the second morning crossed into Cirque de Mafate. The terrain in this caldera is too rugged for roads, so it has a quiet and pristine feel to it. This feeling would, of course, be broken the moment a helicopter appeared to deliver supplies to the inhabitants (and one did), but we were treated to an illusion of grand solitude throughout our stay. Perched on the caldera’s edge, we could see across to the precipitous wall on the other side. Below us were valleys, peaks and plateaus; several of the latter were dotted with the tiniest pinpricks of color — houses in little villages. All day we hiked through this wilderness, the clouds advancing up the gorge that led to the sea.

We finished our hike in the drier Cirque de Cilaos, where we could board a bus back to Le Port. And then it was time to tackle the passage to South Africa. The weather reports looked ideal if we left one day later, so we grabbed our last chance to find Piton Cabris. We boarded the first bus at dawn, bound for the edge of Cirque de Mafate, and started our hike down into the gorge. Tropicbirds fluttered overhead, leaving their cliff nests for a day of fishing. The trail slanted down the steep side of the gorge until it came around a curve. There before us lay a wide, gravelly riverbed, framed on both sides by the walls of the caldera. Rising from the river was a lush, green cone: Piton Cabris. It was exactly the same view as in my cutout, the picture that had kept me going in the heat of Darwin and the wet and nauseating night watches of the Indian Ocean. Yes, it had all been worth it. And I didn’t think there was any way our original route could have brought us somewhere better. If I were to do it again, I would take the southern route once more.

Ellen Massey Leonard circumnavigated the globe by age 24. She and her husband, Seth, recently cruised the Alaskan Arctic aboard their present boat, Celeste. They reached the northernmost point of America at Barrow, and are currently moored in Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands.