Like many Taiwanese boats built in the 1980s, my Kaufman 47, Quetzal, was slathered in teak. Side decks, foredeck, cabin trunk, handrails, coamings — a veritable forest afloat. As someone capable of rationalizing almost anything, and because I was able to buy the boat for a great price, I not only accepted the abundance of teak, I embraced it. Of course I knew that practical-minded sailors scorned external wood; indeed, I was one of them before I felt the magic of teak beneath my bare feet, at least on cloudy days when the decks were not scalding. And yes, I knew that teak decks were becoming scarce on new boats and seen as a liability on older boats. But that didn’t stop me from bragging about teak’s unrivaled nonskid capabilities and excellent insulating properties. And I loved the aesthetic, boasting that a handsome renewable resource like teak softened the cold, oil-derived glare of a utilitarian fiberglass deck. I was more than a teak-deck apologist; I was a teak-deck snob.

I bought the boat in 2003, and to my dismay, my decks started to show signs of wear and tear just a few years later. I sail a lot, around 10,000 miles a year, and the decks were subjected to cascades of seawater washing over them and the roughshod treatment of an offshore training vessel doing her job, scribbling rhumb lines across the Atlantic. Although I tried, I couldn’t ignore the screw heads appearing under sprung bungs, the raised and missing caulking on the foredeck and a couple of weathered planks that had splintered. But it was a mugging in Trinidad that hastened the demise of my teak dreams.

I left the boat on the hard for a couple of weeks and hired a highly recommended chap to lightly sand the decks, reseat a few fasteners, replace missing bungs and caulk the worst sections. I returned to a crime scene. My beautiful teak decks had been attacked by a belt sander armed with 16-grit assault paper and smeared with black caulk. At first I wanted to cry, then I wanted to commit a crime of my own. But the damage was done, the life of the decks shortened and, when Quetzal slinked out of Chaguaramas like a shorn English sheep dog, I vowed never again to commission work from a contractor I didn’t know, especially when I was thousands of miles away from the yard.

I kept sailing and mending as I went, but the decks became more and more of an eyesore. When they started to leak, I knew something had to be done. My friends and shipmates grew weary of my incessant fretting over the decks. “Stop complaining and do something,” I told myself, but I could not decide what to do.

I considered replacing them with new fastener-free decks manufactured from templates and mounted with adhesives. These modern teak decks are lovely in every respect except price. When I received an estimate from Teak Decking Systems of $55,000 to $60,000, I became less of a teak-deck snob.

I looked into synthetic teak, also known as fake teak, and was impressed by its appearance and practicality. I gathered a box full of samples and laid them on deck like playing cards. But after boasting about real teak for years, I just couldn’t pull the trigger on installing a synthetic replacement.

I looked seriously at cork and invited myself aboard several aluminum and steel boats to inspect their cork decks. Cork is a natural, sustainable product, but it’s also expensive, the installation seemed beyond my talents and my wife, Tadji, really didn’t like the look. “Cork,” she assured me, “is for wine bottles.”

“I kept sailing and mending as I went, but the decks became more and more of an eyesore. When they started to leak, I knew something had to be done.”

With the realization that every option required the same process to prepare the sub deck, I finally decided to remove the teak, fill the thousands of fastener holes with epoxy, and fair and then spray the decks with nonskid mixed in the paint. My teak-deck days were behind me, alas. It was on to whiter pastures.

The decision was liberating, but I underestimated what a massive job it was going to be to create a utilitarian, low-maintenance fiberglass deck.

I chose the boatyard at Spring Cove Marina in Solomons, Maryland, just south of Annapolis, for the project. Spring Cove has been Quetzal‘s home away from home, and the talented crew had already made many valuable upgrades and repairs over the years. Full disclosure, the yard is owned and operated by my sister and brother-in-law, Liz and Trevor Richards, vastly experienced sailors who have been cruising off and on aboard their Endurance 37, Wandering Star, (including a circumnavigation) for many years.

My cost-controlling plan called for a mix of DIY and professional work. My friends and I were responsible for the destruction phase of the project, removing the old decks. Time was of the essence, as the gap in my training schedule gave us one month to complete the entire project. The doubters were plenty.

The first step was to pull the mast, haul the boat and block it up in the paint shed. Working under cover freed us from weather concerns. Next, we removed every deck fitting — every cleat, clutch, track, anything mounted directly on teak. Fortunately, designer Mike Kaufman and builder Kha Shing used several solid fiberglass islands to mount high-load winches and the traveler base. Still, this was a time-consuming process, requiring one person on deck, one below, and the removal of just about every headliner to gain access to the stubborn nuts anchoring the through-bolts.

The next task, removing the teak, filled me with emotion. With a heavy heart and cold chisel in hand, I surveyed the once-beautiful teak deck and sighed, remembering times I’d gone forward to reef the main or set the staysail, always with secure footing.

I imagined a process for removal that combined controlled physical effort with a sense of quality and renewal, something Robert Pirsig, author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, would understand. “A person who sees quality and feels it as he works is a person who cares,” he wrote. I cared. I was even filled with a sense of tranquility; it was going to be OK. I imagined saving teak planks and sending them to former shipmates as keepsakes.

|

Subscribe Now and Save 50% |

In the most caring of ways, I slipped the chisel under the teak on the coachroof and pried. Nothing happened. I pushed harder; still not much movement. I pushed even harder (I have been accused of having the touch of a Russian midwife) and the chisel popped out and gashed my hand. I cursed, then caught myself. "Come on, Quetzal, I care." I reset the chisel and pushed with all my might. An inch, maybe 2, of teak popped free and cracked at the fastener. Hmm? This was going to require a lot less caring and better tools or it might take a year to strip the teak off.

My team and I regrouped at Lowe’s. Bigger chisels, propelled by 3-pound sledgehammers, started to get results. Then we discovered the rotary hammer and demolition bits. Soon, wood was flying and dust filled the air. So much for Zen and deck souvenirs, this was hand-to-hand combat. The Art of War, by Sun Tzu, became our new playbook. “If you know your enemy, and know yourself, victory will not stand in doubt.” Stubborn teak planks, tenacious old caulk and too many stainless fasteners were the enemy.

My fellow soldiers were dear friends and frequent Quetzal crewmembers. Alan Creaser, from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, was our captain, pushing us through low moments when our knees buckled, backs ached and spirits drooped. Alan, who is currently managing the operations of the legendary Bluenose schooner, reminded us that the original Bluenose, built in 1921, went from "tree to sea in 96 days," crafted entirely with hand tools — surely we could knock off old teak decks in just a few days.

"I am in the sail-training business, after all, and could have been charging them for this invaluable experience. Tom Sawyer wouldn’t have missed that opportunity."

Ron Sorensen, an engineer by trade who has crossed the Atlantic twice aboard Quetzal, has round heels when it comes to my pleas for help. He's a pushover. Bruce Steely fell for Quetzal in the Caribbean, and came to work by boat. His small trawler was loaded with tools, and by the end of the project we had used them all.

I have, unfairly I must say, been accused of being the Tom Sawyer of the sea, working my friends to the bone and offering them nothing but lunch and a few slaps on the back in return. It’s not true. I am in the sail-training business, after all, and I could have been charging them for this invaluable experience. Tom Sawyer wouldn’t have missed an opportunity like that. All joking aside, I am incredibly fortunate to have many talented friends. There is a camaraderie about offshore sailing that breeds genuine friendships.

"Six days after we started, Quetzal’s deck was clean. We didn’t rest on the seventh day; we celebrated at the tiki bar down the road, a questionable call as the next morning proved."

We have had many shared adventures aboard Quetzal, and those of us who sail her feel a deep connection to her. She's our conduit to blue water and the good life waiting at sea. And when she needs work, we all pitch in. It's just not always easy to explain this utopian ideal to spouses. "You paid this guy how much to sail with him and now you're working on his boat for free?"

By the end of Day Two, the teak was in serious retreat. We had most of the cabin top cleared and were making progress on the more challenging side decks. Nothing about the task was easy. We discovered that leaving fasteners in place and zipping them out with a drill afterward was the best tactic. When the head was stripped, we used vice grips to remove them, and of the 3,000-plus screws that once littered the deck, fewer than 20 remain entombed in fiberglass today.

After four days, every last bit of teak was in the scrap bin. We then went after the remnants of the caulk, a tough slurry concocted in Taiwan, but it couldn't hold out against four determined air sanders. Six days after we started, Quetzal's deck was clean. We didn't rest on the seventh day; we celebrated at the tiki bar down the road, a questionable call as the next morning proved.

Quetzal's deck is a composite construction with Airex foam coring. The top layer of fiberglass is ½-inch thick; the Airex is about 1¼ inches; and the bottom layer of fiberglass is ¼ inch, making for a very stiff deck. A key attribute of Airex is that it resists water, and a close inspection and some heavy-footed stomping about the teakless deck revealed no obvious delamination. The next step was to fill all the screw holes using West System epoxy filler. Yard manager Don Reimers then suggested adding a layer of fiberglass to ensure a watertight deck. Don, who has also crossed the Atlantic aboard Quetzal, joked, "I don't want to be leaked on again on my next crossing."

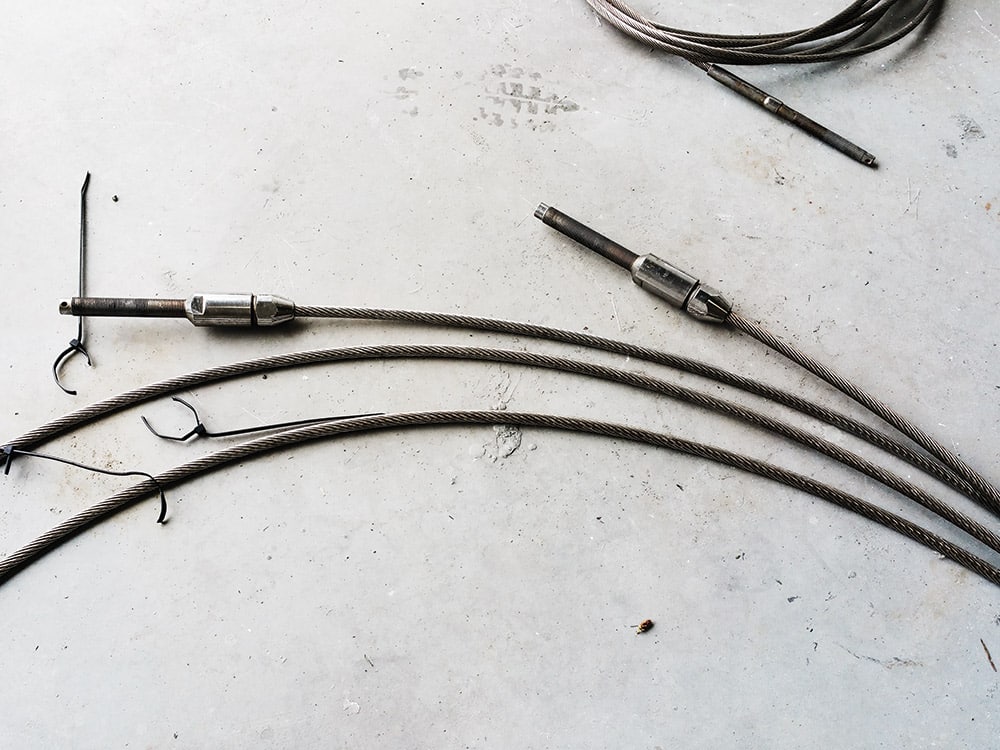

While the yard crew worked on the deck, a new team of volunteers — Bob Pingel, Dan Stillwell and Earl Bennett — arrived to relieve Alan and Bruce, while Ron soldiered on for a second week. With the mast in a rare horizontal plane, we seized the opportunity to replace the standing rigging, add a new wind transducer and pull fresh wires through the spar. We also serviced the winches. In typical Quetzal fashion, a full-blown refit was sandwiched into the deck project.

When the new layer of fiberglass cured, the decks were primed with Awlgrip. It would have made sense to finish painting before reinstalling the deck fittings, but my tight schedule dictated otherwise. Every fitting would have to be taped before the final three coats of Awlgrip were applied. Another friend and Atlantic-crossing shipmate, Danny Peter, flew in to lend a hand. The two of us bed and remounted every piece of hardware, including new stanchions and mast rails, using a case of 3M 4200 and squeezing into tight corners below to wrestle a wrench onto wayward nuts.

Eighteen days after we started, I flew to France to captain a canal-boat trip, and returned a week later. I had four days before I was scheduled to set sail on a training passage to Nova Scotia.

To my surprise, Don had not only finished spraying the deck while I was away, he also sprayed the topsides. Quetzal looked stunning, at least 20 years younger. My sister and her son, Will, had cleaned the disaster below, vacuuming out bags of dust and grime. In short order, the mast was stepped, the rigging tuned, the cushions, cutlery, tools, books, charts and everything else was carried back aboard and hastily stowed.

I was still working when my new crew turned up, and after I introduced myself, they promptly went to work, schlepping provisions aboard. Thirty days after the project began, we pushed off the dock and headed north. It’s amazing what you can do with a lot of help from your friends.