The noise was so ferocious,” Malcolm said, “and the lightning was so incessant, you could only see the negative image, only black and white.” Across the table, Fred shook his head at the memory. “I just kept asking, ‘Why does it take so long to die?’”

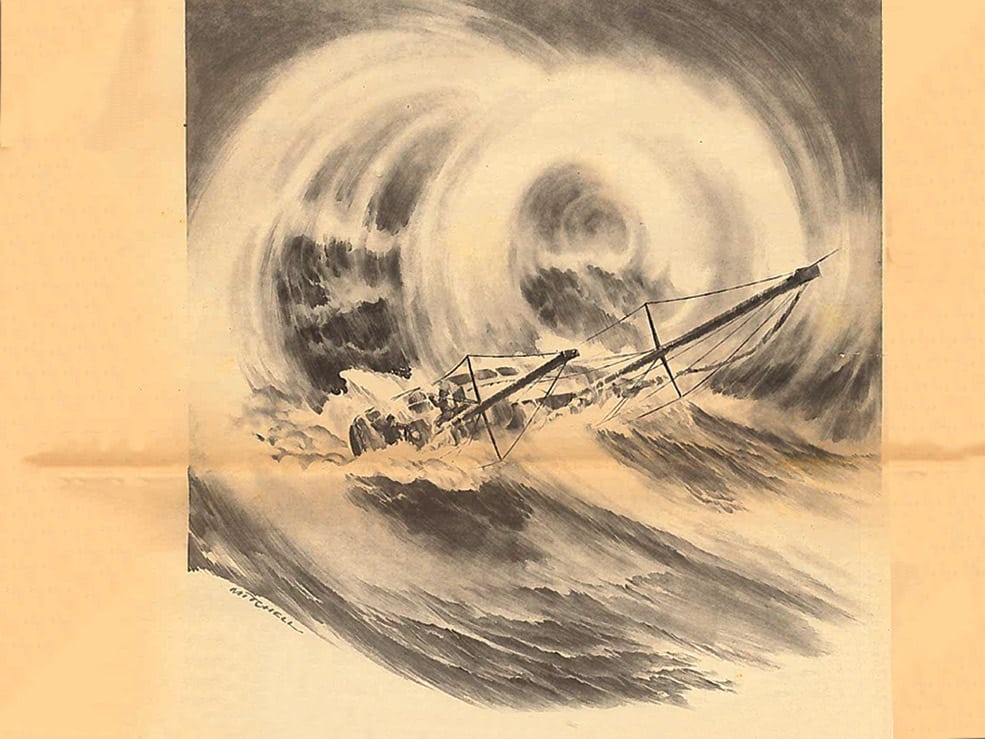

“We were right there when that thing was made,” said Malcolm, pounding his fist on the table. “It was an imperfect no-account storm that formed perfectly, tightly around us.”

They talked like the survivors they were, still awed at the discovery of their own resources, and of their boundless good fortune.

They were half of the four-man crew of Bowditch, a 42-foot steel ketch out of Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts, that was bound for the Bahamas in the final months of 1978. The “thing being made” was Hurricane Kendra. It was the storm that rendered them shipwreck survivors, the tempest that almost killed them all. The one that had them wash up in, of all places, Havana, Cuba.

The final chapter in Bowditch’s life began earlier that fall. The boat’s builder and captain, Frederick Strenz, was 57. A spare, stern man recently retired from his steel company on the North Shore of Massachusetts, he’d sailed much of his life. Longtime friend and legendary boatyard owner Sturge Crocker credits Strenz’s eventual triumph over the ocean more to a lucky roll of the dice than skill. “I told him anyone with that kind of luck ought to invest heavily in the lottery.” Strenz’s ultimate dream took on tangible proportions in 1969, with a $50 set of mail-order blueprints from naval architect James Kerr. The aspiring boatbuilder had earned a graduate degree in engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and had at his disposal some of his own ace welders. Gradually, a lattice of steel sheaths and iron crossbeams formed Bowditch’s skeleton, which was fortified with panels of rust-controlled Corten steel. He was proud of his achievement — “a little too proud,” one crewmember later remembered. “Never worry about this boat,” Strenz said on several occasions. “You can haul it up 20 feet and drop it, it’ll withstand that. And when bad weather starts, all you have to do is button up and go below. Just button up and go below.” Manchester, as it was called at the time, is a quiet, quaint New England town built around a small harbor. It has a yacht club with a gazebo for picnics, and a broad, calm basin for a few dozen cruising boats and a small flotilla of Herreshoff 12½s. Many of the town’s families settled here early and stayed. Most have some bond with the sea, and as a result, with each other.

That is how Ben Sprague got wind of the voyage. A strapping young buck of 22, Sprague was a competent sailor who’d spent the summer as an instructor at the Manchester Yacht Club. Fresh out of college and without a job, he was ripe for adventure.

Another crewmember, Malcolm Kadra, was on leave from the state police. He was the golden boy of the detective division, with Paul Newman good looks. But the years of being an undercover narc had taken their toll, and one night he walked into the dispatcher’s office, laid down his firearms and confessed he didn’t trust what might happen if he kept them that night. His sailing experience was limited to day trips, but at 39, he found himself bored and restless; he was still in prime physical condition, helped by year-round daily ocean dips.

Strenz was not superstitious, either on land or sea, so on Friday the 13th of October, damn superstition, the captain and his crew of three sailed out of Manchester Harbor.

The last crewmember, Dick Stanley, was an experienced bluewater sailor. In fact, the year before, he’d sailed Bowditch on the reverse course of the ’78 trip, from the Bahamas to Bermuda, then back to Manchester. He knew the boat and the skipper, and felt he could handle both. But unforeseen business would make Bermuda Stanley’s only port on this passage.

By early October, the crew was assembled and the hurricane season was on the wane. After some artful stowing and last-minute maintenance, departure day arrived.

There are certain superstitions derived from sea lore that only an ignorant or arrogant man would deny, such as not beginning a voyage on a Friday. But Strenz was not superstitious, either on land or sea, so on Friday the 13th of October, damn superstition, the captain and his crew of three sailed out of Manchester Harbor. Next stop: Bermuda.

According to pilot charts, at that time of year you can expect gale-force breezes every fifth day, so no one was too concerned when the winds picked up on the third day out. As day turned to night, the seas grew, from 5 feet to 10 feet. The crew dropped all sail and started towing warps, trailing lines to slow the boat and maintain direction in the following seas. As they plowed through the Gulf Stream, the gale persisted through the next day and the next night. They settled into a routine, changing watches, bailing and steering.

As dawn broke at the outset of the gale’s third day, Kadra relieved Stanley on watch and saw the storm break, the skies clear and the seas settle. By noon they started peeling off their long underwear and enjoyed their first midocean bath. Although the storm had brought some anxious moments — the 8-foot fiberglass sailing dinghy slipped loose of its chocks and nearly slid overboard — they felt a calm exhilaration and confidence overriding their fears.

They arrived at St. George’s, Bermuda, by nightfall of the eighth day and tallied their losses: a few broken shackles, a missing taffrail log, but nothing that couldn’t be fixed or replaced with a few days in port. That night at the White Horse Pub, they quenched their thirst with rum and tonics, toasted providence and regained their land legs. Stanley made arrangements to fly back to Massachusetts for his son’s football game the next day. Weathered and able seaman Fred Nataloni was standing by in Manchester to take his place.

Nataloni was a meticulous fellow: short, compact, bandylegged. There was a sense of order and caution about him that came from 30 years of piloting planes and boats. It might well have been his instincts for survival that enabled him to keep his job as Massachusetts’ director of marine and recreational vehicles through three different administrations and the explosive politics of Boston’s Beacon Hill.

Kadra’s friendship with Nataloni went back a long way. Once Nataloni arrived on the island, he knew Kadra was hesitant to continue with the journey from Bermuda to the Bahamas, but he took pains to reassure him. “It’s a milk run. It’s all downhill from here,” he said.

It was their friendship, and only their friendship, that persuaded Kadra to continue the voyage. Not that Nataloni didn’t have his own misgivings. Upon his arrival at St. George’s, his sense of order was assaulted by the condition of the boat, by gear and equipment lying helter-skelter. The halyards were in need of resplicing, and the emergency gear consisted mainly of a World War II-era inflatable raft.

On October 25, after five days in port, they hoisted sail. Destination: Man-O-War Cay, Bahamas, an 860-nautical-mile broad reach in open ocean. Earlier that day, before departing, Nataloni took a motor scooter out to the airport. It was his custom before flying or sailing to check the latest satellite weather charts. “There was a system tightening southeast of Bermuda, blowing northeast about 45 knots,” he recalled. “It would disrupt the trades for at least another day, and then on Friday, fair weather would return.” Strenz voted to go ahead as scheduled, assured that by Friday they would be on a direct rhumb line with the Bahamas. Their last task before casting off was to file a float plan with the Coast Guard. They predicted an ETA for Tuesday, October 31, six days away.

The weather charts proved accurate, and on the second day out, the seas calmed, along with Kadra’s stomach, and all the sails were flying. By the fourth day, they felt invincible, succumbing to the euphoria of several days of fair winds and fine weather. Kadra began eating what he was cooking, Sprague’s saltwater hives cleared up and Nataloni forgot he was going to be gone only a week and the time was almost up. And the captain? Strenz was happy to be one day ahead of schedule and flying along, making 170 miles a day. Once Bowditch was secured in Man-O-War Cay, he would fly home, wind down business as the town’s building inspector, pack his clothes and gather his wife, Olga, and return for the winter.

On Saturday, Bowditch‘s crew toasted the trip thus far with Amstel beer and noted, with no real concern, that it was curious to have seen only one ship in the midst of a normally busy shipping lane.

With no radio weather band, they couldn’t know they were on a dead collision course with a hurricane, and one of the fastest-forming systems on record in the North Atlantic.

Strenz knew navigation, but Nataloni understood weather, and he realized right away that he didn’t like the wispy, high-altitude cirrostratus clouds he saw as he came on deck to relieve Kadra at dawn on Sunday, the fifth day at sea. “I told Mal [Kadra] that was trouble coming from the northeast, but I didn’t say much to anyone else,” he recalled. “We were already at a point of no return.” But the silence lingered that morning over a breakfast of scrambled eggs, sausage and coffee. It would be their last food for several days.

By noontime Sunday, the sun was cast over, the barometer was dropping and the wave heights increased in unpredictable directions. As Kadra wondered how he let this happen again and braced himself mentally, Sprague and Nataloni started securing the ketch. The reaching jib was dropped first and stowed on the foredeck. Strenz ordered a barometer check hourly. By 1600, the genoa and mizzen were doused, the decks cleared and the main reefed down to the lower spreaders. “We were holding course on a reach,” Kadra said. “It was blowing about 35 knots, seas running 15 feet. We didn’t know then how bad it would get.”

With no radio weather band, they couldn’t know they were on a dead collision course with a hurricane, and one of the fastest-forming systems on record in the North Atlantic. Kendra was short-lived, but while still a force, recorded winds in Miami gusted to over 100 mph.

It wasn’t until the winds howled at 45 knots that Strenz agreed to strike all the canvas and continue on by motor alone. “The main was eased out so far to starboard,” Nataloni said, “that one of the battens got hung up in the lower spreaders. Using brute strength, [Kadra] and [Sprague] tore 6 feet of track from the mast getting the mainsail down.”

By then, it was 1900 and dark. The barometer was in free-fall. Strenz was in the cockpit, nervous but stone-faced. “OK, we’re going to two-man teams. You and Mal [Kadra] go below and get your rest,” he said to Nataloni. They weren’t below 15 minutes when they were called back on deck. “Pump the bilge!” Strenz yelled, as churning foam pooped the helm in an almost constant assault.

Anticipating a long night, Sprague and Strenz climbed down the companionway to try to rest. And then it happened.

“What do you think, Fred?” Kadra asked bleakly as he turned to Nataloni at the helm. Nataloni started to utter some half-felt reassurances about “keeping this thing going” when the first knockdown came. Any remaining thoughts of “buttoning up and going below” were doused for good.

Strenz remembers Bowditch “spinning like a compass needle and rolling over like a dead horse, on its starboard side.” Nataloni cut his hand when he was slammed against the binnacle. Kadra clung to the helm, absurdly thinking, I’m hanging on to the wheel and I’m underwater. When am I going to come up? By the time Sprague and Strenz collected themselves below, the boat had righted itself. Strenz, aching with bruised ribs, took the helm; Kadra and Sprague manned the pumps. They later figured the bilges had swallowed 125 gallons of seawater through the vents and hatch openings. Electrical power was gone.

By now, the seas were confused as the low pressure tightened around them. Their attention was focused on the only matter of consequence: keeping the boat from sinking.

“OK, we’ve got a tough night of it,” Strenz screamed above the howling winds, hoping neither the near panic in his voice nor the heart that had twice suffered heart attacks would betray him. “[Sprague], go below and get some crackers and bourbon,” he said. They passed around the bottle, under orders from Strenz, to keep their strength up. No one had yet thought of abandoning ship. And nobody but Nataloni was even aware that the World War II relic of a life raft had washed overboard on the knockdown, leaving only the small sailing dinghy.

Still the winds increased in ferocity; the sea rose up and crashed down with vicious impunity; and the needle bottomed out on the barometer. Thunder enveloped them as rain pounded down from seemingly every direction, making even breathing difficult. It was with the thought of “hiding in the head and locking the door” that Kadra went below, shortly before midnight. His last recollection on board was nibbling on a piece of wrapped cheese he found floating in the diesel oil and seawater lapping around his knees, nauseated by the smell of fuel from the now dying engine.

Suddenly, a mountainous wave came and lifted any further responsibility for Bowditch from her tired crew’s hands. It was the second knockdown. She lay on her side, her mast underwater, the dinghy jammed against the companionway hatch, Kadra trapped below. As Strenz shouted unconvincingly from the helm, “She’ll come up, she’ll come up. We’ve got to swing the wheel around the other way,” Sprague used all his young muscles to free Kadra. As for “coming up,” Kadra knew better as he watched the engine, flooding with water, race out of control. Bowditch‘s fate was sealed.

As Kadra safely emerged from below, rushing water filled the boat quickly, sending her to an ocean grave. There was disagreement later, but Strenz believed that a waterspout had risen up, grabbed his “unsinkable” ship and, in under a minute, sank it.

Only when the hull was almost totally submerged did Bowditch right herself for the last time. Sprague clung to a shroud, thinking, So this is what it’s like to drown. “There was no logical explanation on how we would survive,” he said. “It was just a question of how ugly it would be.”

“Don’t worry, I’ve been in tighter spots than this,” Kadra shouted across to Sprague, snapping him momentarily from his despair, though, of course, he’d never been in any such spot. Meanwhile, the crew searched for one another and the dinghy, hoping not to be pummeled by it in the crushing seaway. Suddenly, Nataloni surfaced from beneath it and saw Strenz. Somehow, incredibly, the four came together around the capsized but still floating dinghy. It was 0010 on Monday when Bowditch disappeared beneath the waves for good. It had taken less than half an hour to bring her down.

Back in Nahant, Massachusetts, Stanley had returned from a Sunday afternoon Patriots game. The CBS Evening News reported the position of a major storm system that was “safely out to sea” in the Atlantic. After dinner, he plotted the course. The spiraling storm called Kendra, he estimated, should be about 60 miles northeast of Bowditch’s position. About that time, Nataloni’s wife, Nancy, called Stanley, uneasy. They decided to contact the U.S. Coast Guard in Boston and Miami, as well as the Bahamian coast guard, pleading futilely for a search party. “We can’t launch an official search party until they are overdue,” was the collective response. The float plan they’d filed wouldn’t make them overdue for two more days. Meanwhile, out at sea, clinging to the overturned dinghy, Kadra took account of the situation: “We were alive. That was a victory in itself. We were together, with not too many injuries, and we mostly still had our strength and determination. I knew it was dire and it would take a long time to die, but I didn’t dwell on it.”

Our heads were underwater as much as they were above it. The occasional burst of lightning was the only time we actually saw each other.

The survival effort in the water began with shaking off their water-laden boots. Inadvertently, a sock came off with Kadra’s boot, and despite the enormity of his discomfort and anxiety, nothing compared to the annoyance of having one sock on and one off. So, in a move he would later regret, off came the other sock. But then he began choking on, of all things, the life jacket! Traitor, he thought, and as he struggled to adjust it, a wave came and lifted it away. Only a pair of jeans, a T-shirt, foul-weather pants and jacket, and a towel he’d thrown over his head prevented him from total exposure.

Nataloni was not so fortunate. Shorts bared almost half his body, and soon, even the tropical current started to freeze his blood. He swallowed a lot of seawater and was vomiting, screaming and urinating freely. Then, he lost control of his bowels. He tried to remember what he’d heard about hypothermia and recalled that the end would be peaceful, even euphoric. Delirious, he let his fingers slip free of the hollow centerboard slot he’d been hanging on to, mumbling to Kadra, “I can’t make it anymore. You know what to tell Nancy and the kids.”

Kadra, pounding his fist on the dinghy, replied, “You hang in there and don’t let go. You go when we go.”

“It was like being in a giant washing machine,” said Sprague. “Our heads were underwater as much as they were above it. The occasional burst of lightning was the only time we actually saw each other.”

At daybreak they started to bail out the dinghy. By midday it was stable enough to hold Kadra. Then, one by one, they climbed aboard and took stock of what they had: They were four 6-foot men in an 8-foot dinghy with two oars and oarlocks, two knives, two life jackets, a hundred-dollar bill and a piece of gum. All the survival gear, emergency rations and water had sunk with Bowditch, and no one would even start worrying about them for a couple more days. Alone in the wide Sargasso Sea, they focused their dwindling energy on keeping their small boat pointed into the waves, alternating positions every hour. Shipping too much water and being tossed out was not an option.

On Tuesday morning, the wind and waves abated and the crew began to plan their survival. Water was the key, but they soon learned that chasing random squalls was a waste of energy. To stave off dehydration in the broiling sun, they poured seawater through their foul-weather jackets during the heat of the day, stopping at 1600 so they would dry off before the chill of nightfall. Headgear was crucial to keep them both warm and cool, and they took turns sharing the two towels they had.

Sleep was impossible, and the effects of the trauma were taking their toll. Nataloni heard music from the now silent sea. He was rethinking his skepticism about the mysteries of the Bermuda Triangle when a three-masted vision appeared to him on the horizon. They would all remember imagining the whir of engines, and Kadra could describe an entire city he swore he saw. To keep an edge on reality, they ceremoniously called off the passing hours — and prayed. Kadra asked the question that was present on all their minds, the notion of cannibalism. The conversation was short, the answer unanimous. In the event of death, they would strip the deceased’s body of necessary gear and bury him at sea. The flesh would not be sacrificial, but it would not be ballast either.

Tuesday was also the day of their scheduled ETA in the Bahamas. They had been adrift since just after midnight Sunday, and Nataloni knew it would be at least another 24 hours before a search party was launched. As he calculated the potential for rescue, a shearwater flew in close. Nataloni casually studied the seabird, curious about its midocean existence, but now his interest was survival. He grabbed an oar, but Kadra protested his lust to kill and instead shouted at the bird, “Go for help.” Was it magical thinking that the solitary bird he saved might find them deliverance?

Nicholas followed the bird’s long-winged flight in and over the 15-foot swells when he saw something … orange. It was Nataloni’s life jacket waving frantically in the wind.

They settled back to the task of scanning the horizon for squalls when a monstrous, magnificent rainbow appeared. Instinctively, Kadra shouted, “We’re going to be saved.”

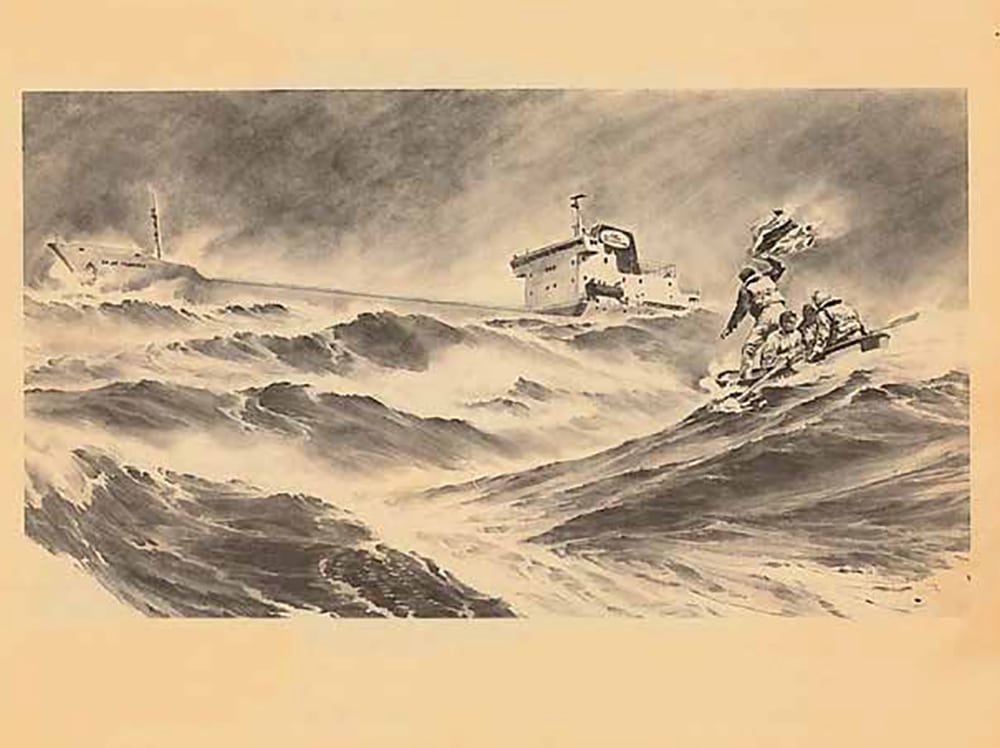

Sprague was the first to spot it, a half-hour later: “It’s something white. It’s a bridge, the bridge of a ship!” They all looked, and this time, they all saw it. It was more or less a mile away. “Row!” Strenz yelled to Sprague and Kadra. “Maybe we can close the gap.” Then Sprague spotted a man running on the deck. “Our Father, who art in heaven …” he prayed. Nataloni waved his orange jacket frantically.

On board the Cuban tanker 24 de Febrero, only a young seaman had ventured on deck after the storm. En route from Holland to Havana, the 450-foot ship had altered course to avoid the hurricane. Nicholas, experiencing his first trip to sea, was crouched in a stairwell looking for birds. Then he saw it. A solitary shearwater, searching for respite, landed on deck. As he lunged for the bird, it disappeared into a trough. Nicholas followed the bird’s long-winged flight in and over the 15-foot swells when he saw something … orange. It was Nataloni’s life jacket waving frantically in the wind. He waited for another trough to pass, and then he was sure.

The crew of the long-gone Bowditch looked for a sign of recognition, a change in the tanker’s speed and direction. Seconds passed like hours. No one spoke. Sprague’s optimism was beginning to fracture when he saw the steel hull begin a gentle turn that would put them in its lee.

It wasn’t until Kadra reached for the rescue line being paid out from the deck 30 feet above that he realized how weak he was. Still, his determination was fierce: “If I had to use my teeth, I would have gotten up that rope ladder.” Only with his feet planted squarely topside did he loosen his death grip. The captain’s voice crackled across the ship’s PA system: “Cuidado, tal vez son locos.” Be careful. They might be crazy. They’d made it. After 41 hours adrift in a boiling sea, they no longer had to be brave or stoic, and so they dissolved in tears and hugs and laughter. But they hadn’t counted on the extreme emotion among the crew of 24 de Febrero. All 31 members were also crying and hugging. There is no nationalism at sea, thought Sprague.

During the two days it took to reach Havana, they were treated royally. The first offering was a quarter cup of fresh water, soon followed by gallons more. Four officers vacated their staterooms and carried them to the showers. There they exchanged layers of salt crust for clean, borrowed clothes. The captain appeared with the best Cuban cigars and rum. “This ship is your home,” he said, and hugged them. The first radio message received from a Cuban ship in 20 years was picked up on Cape Cod. It was brief. “We are safe. No injuries. Arrive Havana November 2.”

The fanfare in Havana was less hospitable. After the ritualistic embrace and pictures, they were taken to a dark, dank room where police and immigration officers questioned each man separately. Finally, with an escort of armed guards, they were led to an abandoned mansion, seized during Fidel Castro’s takeover and converted into a prison for political dissidents. Billboards along the route warned, “North Americans will be invading us. Be prepared.”

Conspiracy-seeking Cuban officials quickly learned that Strenz lived on Spy Rock Hill Road. “On whom do you spy on Spy Rock Hill Road?” they asked. On top of that, Kadra was a Massachusetts state trooper, Nataloni a state administrator, and Sprague couldn’t deny that his father worked for the CIA. Who were these gringos?

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Swiss Consulate officials, acting as go-betweens, conferred with the U.S. State Department to rustle up passports and the necessary plane fare. Eventually, the quartet was cleared to go home.

They would not see their rescuers, their saviors, again until four days later, as they were boarding a jet for Canada. But the bond was already established. The 8-foot nameless dinghy on which they survived the maelstrom was mounted on the deck of 24 de Febrero — a permanent symbol of a unique friendship.

On the second anniversary of that fateful trip, the Bowditch crew and many of those from 24 de Febrero met in Canada for a reunion. They drank a slow toast, the first of many, and relived the adventure that had forever changed their lives. The conversation became sentimental. Kadra raised his glass “to Simone,” the tanker’s captain. Nataloni’s eyes welled in remembrance of the Cuban sailor’s parting words: “When I am a very old man, I sit down with my grandchildren, this is what I tell them … this ordeal of yours with the sea.”

It’s now been nearly four decades since that fateful encounter with a hurricane that was “safely out to sea.” For the men who survived, it informed their lives.

Strenz swore he would live to sail the seas again, and he did. And though he clung close to shore and followed weather reports with something akin to religious fervor, he did sail again — on Bowditch II. Strenz died, on land, in 2008, at the age of 87.

Kadra went on to more sea adventures, diving for treasure on Spanish galleons off the coast of South America and spending some frightening time in a Colombian jail before returning to familiar shores.

Nataloni continued to serve the Commonwealth of Massachusetts through six administrations. The memories of that voyage haunted him until his death in 2012, at 83.

Sprague has since logged thousands of offshore sea miles in powerboats and sailboats. Still, he lives every day with that experience aboard Bowditch and the crew that saved him. He is looking forward to someday reuniting with some of his Cuban brothers. This time, again, on their home turf.

Lifelong sailor Beverly Schuch was a correspondent for CNN for 16 years. She taped extensive interviews with the Bowditch survivors in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and recently re-interviewed survivors Malcolm Kadra and Ben Sprague for this account of their remarkable tale.