OK, maybe it wasn’t love at first sight, but it was close. Built of wood and epoxy, and launched on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten in the winter of 1977, the 75-foot catamaran Ppalu was and is my dreamboat. At the time, I was a hotshot pro racer with a 30-foot cat and my own sponsor, who sent me to Philipsburg “to broaden my horizons.” Why not? Ppalu was the world’s biggest, coolest cat! With 200 others, I literally helped lift and carry Ppalu into Simpson Bay Lagoon for her first sip of salt water, and then and there I said, “When I grow up, I’m going to own that boat.”

Whether I ever actually grew up is the subject of considerable debate, but two things are irrefutable. Decades later — last year, in fact — I became the owner of Ppalu. Even more remarkable, not long after, I came very close to losing her in the very same waters where we began our journey.

Of course, when it comes to boats and sailors and sea tales, truth can be stranger than fiction. And in the many years between those wonderful and terrible moments in Simpson Bay, Ppalu saw other highs and lows. At one point she was a dominant force in the glamorous world of Grand Prix ocean racing. Later, she was reduced to inglorious duty taking sunburned tourists for boozy boat rides. Which is just about the time we met once again.

So, yes, in many ways, Ppalu is the cat with nine lives. But wait a second. I’m getting ahead of the story.

She was named for the last of the Polynesian navigators, the ppalu. In the Santa Cruz archipelago in the Solomon Islands, where every chief still has his ppalu, they continue to ply their trade. The skills and knowledge — specifically, the aveia, or star charts — are passed down from a senior ppalu to a young apprentice, so the tradition is oral and ongoing. The youthful ppalu then spends the rest of his life honing and practicing what he’s learned.

Fittingly, I guess, it seemed like I’d spent most of my life following my waterborne Ppalu.

Designed and built by the legendary Caribbean catamaran visionary — the late, great Peter Spronk — the ketch-rigged Ppalu was years ahead of her time. With lapstrake hulls fashioned of epoxy and Bruynzeel plywood over laminated frames, Ppalu was easy to build, light and dry. Spronk went with the split rig so she’d be simple to sail shorthanded and in big breeze. Right from the outset, the big cat proved he got his figures right.

Ppalu began her adventures competing in the premier multihull contest of the time, the Trade Winds Race. It consisted of three legs, the first of which was from St. Maarten to Virgin Gorda after rounding St. Croix. The fleet was stacked, and included Phil Weld’s Dick Newick-designed Rogue Wave and Jeff and Ann Klein’s Maho, which had already broken the 30-knot speed barrier — in 1972! Ppalu blew everyone’s doors off, finishing five hours ahead of Weld’s 60-footer.

And then, in a bleak preview of coming attractions, she promptly ran aground.

While undergoing repairs, she was five hours late for the start of the second leg, to Martinique — and she still beat everyone to the French island by three hours. The final leg, back to St. Maarten, was a foregone conclusion. Ppalu was the runaway victor of her inaugural event.

The dominating performance didn’t go unnoticed. Especially impressed were French offshore superstar Eric Tabarly and his countryman and protégé, Olympic medalist Marc Pajot. They thought so much of the boat that they persuaded their sponsor to charter it for 1978’s inaugural Route du Rhum, a solo transatlantic race from France to Guadeloupe. So for that event, thanks to the corporate backer, Ppalu sailed under an assumed name: Paul Ricard.

And what a race it was.

It actually signaled the coming of age for offshore multihull ocean racing. The winner, in a famous finish, was Canadian Mike Birch, whose 36-foot Newick trimaran, Olympus Photo, beat Michel Malinovsky’s giant ultralight monohull, Kriter VI, by a mere 98 seconds. Well, hello multihulls.

But Ppalu/Paul Ricard had a rough go of it. Before the race even began, Tabarly fell ill. Pajot took the reins, but right after the start, while setting his chute, he ran over an anchored spectator boat (dismasting the little buggah) and broke his wrist. Even so, he cut away the innocent bystander’s rig and kept going, and by the second day had a sizable lead. That’s when he hit a submerged container and sank a hull. Ever resilient, the boat was salvaged and towed to a beach in Spain, where three fishermen repaired the hull — with cement! Three days later, a three-man French delivery crew set off for Guadeloupe aboard Ppalu/Paul Ricard; her race, of course, was over, but the crew reckoned they could at least partake in the post-race parties.

They never expected to beat the entire fleet to the island.

And there, after a very star-crossed transatlantic trip, Ppalu fell into obscurity.

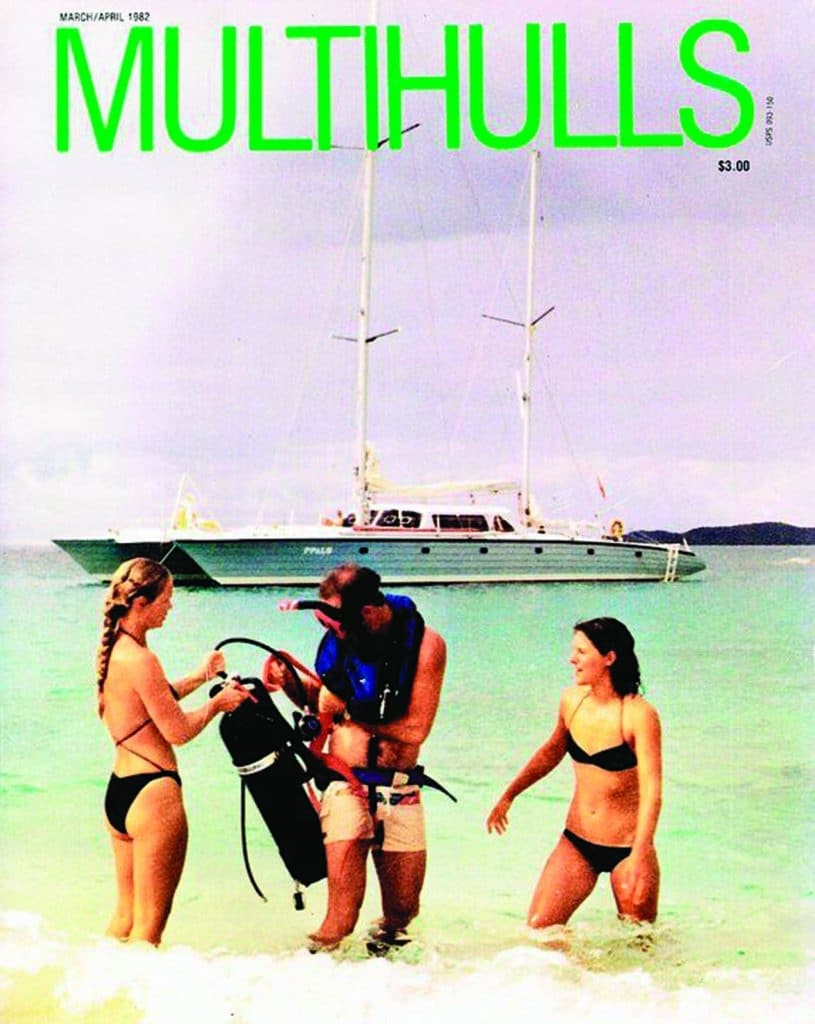

The story goes that she was purchased by a shadowy dude from Florida and wound up in Tortola, British Virgin Islands. There she entered into the day-charter trade, never to race again. The high point may have been in 1982, when Ppalu made the cover of Multihulls magazine with a group of happy dive charterers on a Virgin Islands beach. In reality, she’d become a grim “cattle-maran”: unloved, unkempt and flushed into a downward spiral that would be her lot for years to come. Much time passed before Capt. Odel Smith became her skipper, and for the next 15 years, with string and a prayer, he kept her alive.

Which is where I came in.

Between gigs as a professional sailor captaining high-profile race boats and running Spronk cats up and down the Caribbean, after years of making offers to purchase Ppalu, finally one was accepted. There was good news and bad: The rig was sound (great!) but the boat was sinking (uh-oh). She needed a total refit.

We had a nail-biting sail from Tortola to St. Maarten. With two other crew onboard, we added two more bilge pumps to the three already installed and motored over to Virgin Gorda, where we anchored off the beach in front of Virgin Gorda Yacht Services in case we needed immediate assistance. So far, so good. After waiting for calm weather that never materialized, we bit the bullet and beat across the Anegada (Oh My Godda!) Passage to St. Maarten, where we anchored near the Simpson Bay Bridge with broken steering and lazarettes full of water. The next day we passed through the drawbridge into the bay amid cheering and horn blowing from the St. Maarten Yacht Club and tied up at Lagoon Marina, right next door to where Ppalu was launched 35 winters before.

She was home.

And I thought to myself: I must be mad.

Now there are three places in the world where I’d resurrect an old Spronk cat, and St. Maarten, of course, was one of them, as long as master craftsmen Jon Westmoreland or Louis St. Bernard were involved. But Jon was rebuilding his 50-footer, Ikhaya, the schooner-rigged cat Peter Spronk had built for himself in 1976. And Louis, who’d built and repaired Spronk cats right up to his dying day, had only recently and tragically passed away from throat cancer (wear your respirators!).

My second choice would’ve been Barbados, the land of Spronk catamarans, where most of the old designs are still sailing and there’s a unique haulout facility especially designed for the boats. But it would be a long sail — and dangerous for a leaking boat — and you need to import supplies with you. Um, never mind.

That left St. Kitts, a mere 48 miles from St. Maarten. Not only was it close, but there was plenty of skilled labor there, including Philip Walwyn of St. Kitts Boatbuilding and many of his former craftsmen, who’d all been building wood/epoxy cats for 40 years. Perfect. After the steering was repaired, we sailed Ppalu over and hauled her at St. Kitts Marine Works. I hired a couple of Philip’s Rasta guys, and with my fiancée, Joanne “HQ” Roberson, we hauled the boat and I made a plan.

As it was unclear why the boat wanted to, you know, sink, we first needed to stabilize her. Under sail, the lazarettes filled with water and more came in through the port forward cabin, as well as the hatches and chainplates. I’d hauled her half full — and nothing ran out! Where the hell was all the water coming from?

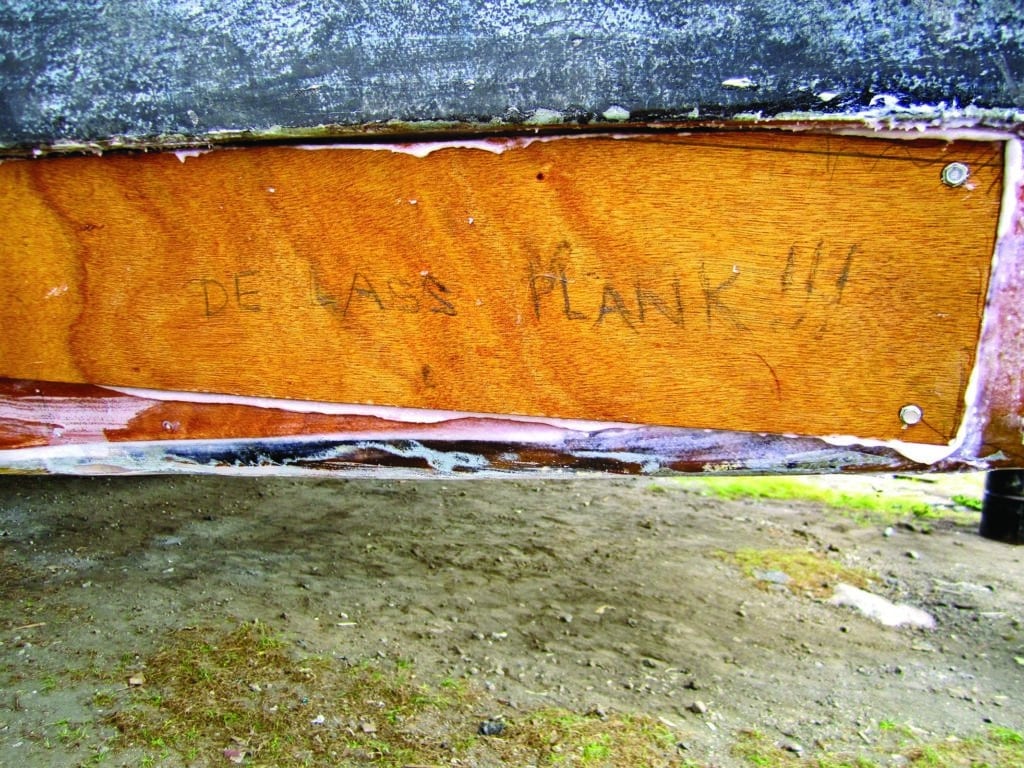

Rotten planks were the answer. Ppalu is a clinker-built boat, so the first item on the list was easy: Replace those foul ones, all 22 of them.

Then things got complicated.

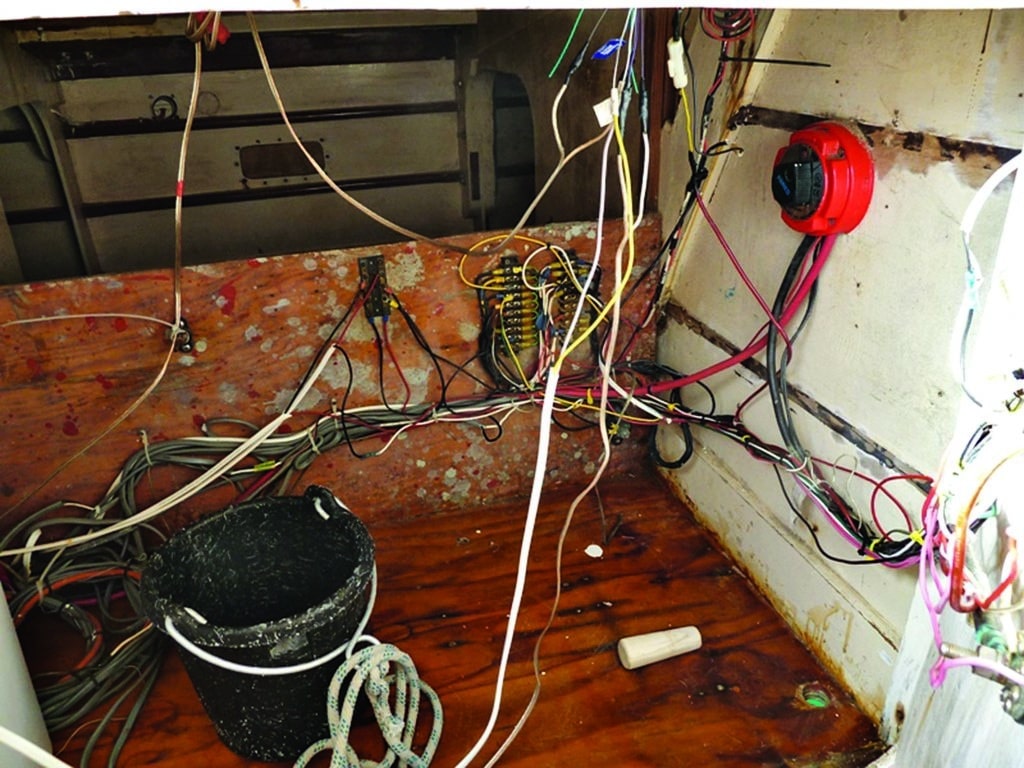

Let’s start with the six cabins, which were a mess. I decided to rebuild just two to get the boat sailing again. Next was the deckhouse, which had leaky windows when it rained; when we replaced those, we added new port lights too, and while we were at it we redid the lighting and electrical systems, added new sailing instruments and even threw in new winches. The main saloon had been “redesigned” to accommodate fat tourists at a feeding trough. (Sorry: It’s true.) A fold-down table with a curved settee, and a proper nav station and galley rectified that problem.

Now we were getting somewhere. I began to see a proper world-cruising layout, ideal for a couple of friends, HQ and me.

Of course, then came the rotten centerboards, one of which had been stuck in the up position for two years. The rudders were nasty, pitted aluminum. The decks, where the hatches had been screwed down without bonding material, were soft. All of it had to be addressed. So too did the steering system (a single helm going to double steering stations did that trick); the ground tackle; and on and on. Address it all we did. Then we repainted her and bent on a new mainsail and blade jib.

I called it “Project Ppalu,” and there before my eyes it all came together — with a lot of help from my friends.

Through social media, I put the word out that the old lady was being restored, and the response was incredible. Every other day, it seemed, someone sent along an ancient newspaper clipping or magazine article; people I’d never heard of contacted me with thanks for saving the boat. Clearly Ppalu touched a lot of lives. Old friends and plenty of Caribbean businesses showered me with gifts. I was astounded how much folks really cared.

Finally, earlier this year, Ppalu was re-splashed, with plans to hit all the Caribbean spring regattas. In March, I was back in St. Maarten racing a Gunboat in the Heineken Regatta. Ppalu was at anchor in Simpson Bay. It was a beautiful, clear, sunny afternoon. HQ and I went ashore for dinner supplies and were heading back to Ppalu with fresh salmon and a nice bottle of white wine. Glancing out at the anchorage from the grocery store, I noticed that, for some reason, Ppalu was NOT facing the same direction as the other yachts.

Oh, no.

For years I ran a Spronk cat called Shadowfax, which I’d anchored in the exact same spot in Simpson Bay many times. But Shadowfax was 60 feet, not 75 like Ppalu. It made all the difference in the world, for it turned out I’d dropped the hook precisely 59 feet from a small reef with one rock that was 2½ feet below the surface. For the record, Ppalu draws 3 feet.

She found that one rock.

We scrambled aboard literally minutes after she’d grounded, but the starboard hull was already filled up. Not “floorboards floating full,” but filled to the brim. I called my friends, the Coast Guard, the cavalry. Help was on the way. But we lost the race versus the setting sun. As night and the boat both settled in, the rock started sawing through the bottom. One pump, two pumps, an even bigger pump, to no avail. After five hours, we gave up. It was too dark and dangerous to try air bags until first light.

The next morning, after pro divers rigged three air bags, and escorted by a small armada of dinghies, yachts and a small tug, we got Ppalu over to the big boatyard at Bobby’s Marina and hauled her out. The overwhelming damage became overwhelmingly evident: 30 feet of bottom was gone! Along with all the tools, spare parts and everything else that didn’t float. The batteries had gone under and discharged, ruining all the new wiring and fixtures. Everything that was still there was coated with a slimy film of mineral spirits, a single coffee can of which had been left on a shelf. A bloody mess is what it was.

But there were so many silver linings around this dark cloud.

If you’re going to sink, do it in 3 feet of water on an island where everyone knows you and most of them like you. The salvers were great, as was the Coast Guard, who passed by three times during that first night to make sure HQ and I, who were sleeping on deck, were safe and nobody tried to rob us. The yard manager at Bobby’s took command of the Travelift himself. Rob Moore of Ambient Real Life video production, on hand for the Heineken, put together a 23-minute video all about the boat’s history and mishap to get the word out. The yacht designer Dougie Brooks, the last surviving member of the team that put Ppalu together, rolled in to help rebuild her. My friend Anna gave us her townhouse and moved in with her “ex” so HQ and I would have a place to live.

And since I am a normal person just like you and can’t afford to refit a 75-foot wooden boat TWICE, donations have come in literally from all over the world to keep Project Ppalu and her ongoing restoration alive.

As I write, the boat has been planked (again!) and is ready for a glass skin. The lights are on and two of the batteries are holding a charge. The rudder that broke off was easily sleeved and welded, and is ready to be installed.

I’ve come to see this latest challenge as a blessing in disguise. Ppalu was Peter Spronk’s signature piece, his masterwork, and it’s my dream to make her whole again. So many friends and strangers have told me she needs to sail the seas once more. Pretty soon it’ll be time for bottom paint, and then we’ll sling some champagne on the bows and put Ppalu back in the drink.

Right where she belongs.

Below: Ppalu‘s grounding and salvage off St. Maarten.

Click here to see more photos of Ppalu‘s refit. D. Randy West is a professional sailor, an amateur character — or is it the other way around? — the author of The Hurricane Book and a longtime rambler across the Caribbean Sea. For updates on this story, visit Randy’s website, ppalu.com.